Music with Ease > 19th Century Italian Opera > Il Trovatore (Verdi) - Synopsis

Il Trovatore -

Synopsis

An Opera by Giuseppe Verdi

CHARACTERS

COUNT DI LUNA, a young noble of Aragon………………… Baritone

FERRANDO, DI LUNA’s captain of the guard………………. Bass

MANRICO, a chieftain under the Prince of Biscay, and reputed Son of AZUCENA…………………………….. Tenor

RUIZ, a soldier in MANRICO’S service………………………. Tenor

AN OLD GYPSY…………………………………………………… Baritone

DUCHESS LEONORA, lady-in waiting to a Princess Aragon… Soprano

INEZ, confidante of LEONORA……………………………….…… Soprano

AZECENA, a Biscayan gypsy woman………………………..…… Mezzo-Soprano

Followers of COUNT DI LUNA and MANRICO; messenger, gaoler, soldiers, nuns, gypsies.

Time: Fifteenth century.

Place: Biscay and Aragon.

For many years "Il Trovatore" has been an opera of worldwide popularity, and for a long time could be accounted the most popular work in the operatic repertoire of practically every land. While it cannot be said to retain its former vogue in this country, it is still a good drawing card, and, with special excellences of cast, an exceptional one.

The libretto of "Il Trovatore" is considered the acme of absurdity; and the popularity of the opera, notwithstanding, is believed to be entirely due to the almost unbroken melodiousness of Verdi’s score.

While it is true, however, that the story of this opera seems to be a good deal of a mix-up, it is also fact that, under the spur of Verdi’s music, even a person who has not a clear grasp of the plot can sense the dramatic power of many of the scenes. It is an opera of immense verve, of temperament almost unbridled, of genius for the melodramatic so unerring that its composer has taken dance rhythms, like those of mazurka and waltz, and on them developed melodies most passionate in expression and dramatic in effect. Swift, spontaneous, and stirring is the music of "Il Trovatore." Absurdities, complexities, unintelligibilities of story are swept away in its unrelenting progress. "Il Trovatore" is the Verdi of forty working at white heat.

One reason why the plot of "Il Trovatore" seems such a jumbled-up affair is that a considerable part of the story is supposed to have transpired before the curtain goes up. These events are narrated by Ferrando, the Count di Luna’s captain of the guard, soon after the opera begins. But as even spoken narrative on the stage makes little impression, narrative when sung may be said to make none at all. Could the audience know what Ferrando is singing about, the subsequent proceeding would not appear so hopelessly involved, or appeal so strongly to humorous rhymesters, who usually begin their parodies on the opera with,

This is the story

Of "Il Trovatore."

What is supposed to have happened before the curtain goes up on the opera is as follows: The old Count di Luna, sometime deceased, had two sons nearly of the same age. One night, when they still were infants, and asleep, in a nurse’s charge in an apartment in the old Count’s castle, a gypsy hag, having gained stealthy entrance into the chamber, was discovered leaning over the cradle of the younger child, Garzia. Though she was instantly driven away, the child’s health began to fail and she was believed to have bewitched it. She was pursued, apprehended and burned alive at the stake.

Her daughter, Azucena, at that time a young gypsy woman with a child of her own in her arms, was a witness to the death of her mother, which she swore to avenge. During the following night she stole into the castle, snatched the younger child of the Count di Luna from its cradle, and hurried back to the scene of execution, intending to throw the baby boy into the flames that still raged over the spot where they had consumed her mother. Almost bereft of her senses, however, by her memory of the horrible scene she had witnessed, she seized and hurled into the flames her own child, instead of the young Count (thus preserving, with an almost supernatural instinct for opera, the baby that was destined to grow up into a tenor with a voice high enough to sing "Di quella pira").

Thwarted for the moment in her vengeance, Azucena was not to be completely baffled. With the infant Count in her arms she fled and rejoined her tribe, entrusting her secret to no one, but bringing him up -- Manrico, the Troubadour -- as her own son; and always with the thought that through him she might wreak vengeance upon his own kindred.

When the opera opens, Manrico has gown up; she has become old and wrinkled, but is still unrelenting in her quest of vengeance. The old Count has died, leaving the elder son, Count di Luna of the opera, sole heir to his title and possessions, but always doubting the death of the younger, despite the heap of infant’s bones found among the ashes about the stake.

"After this preliminary knowledge," quaintly says the English libretto, "we now come to the actual business of the piece." Each of the four acts of this "piece" has a title: Act I, "Il Duello" (The Duel); Act II, "La Gitana" (The Gypsy); Act. III, "Il Figlio della Zingara" (The Gypsy’s Son); Act IV, "Il Supplizio" (The Penalty).

Act I. Atrium of the palace of Aliaferia, with a door leading to the apartments of the Count di Luna. Ferrando, the captain of the guard, and retainers, are reclining near the door. Armed men are standing guard in the background. It is night. The men are on guard because Count di Luna desires to apprehend a minstrel knight, a troubadour, who has been heard on several occasions to be serenading from the palace garden, the Duchess Loenora, for whom a deep, but unrequited passion sways the Count.

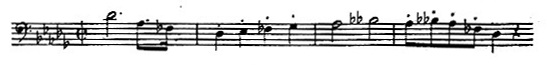

Weary of the watch, the retainers beg Ferrando to tell them the story of the count’s brother, the stolen child. This Ferrando proceeds to do in the ballad, "Abbietta zingara" (Sat there a gypsy hag).

Ferrando’s gruesome ballad and the comments of the horror-stricken chorus dominate the opening of the opera. The scene is an unusually effective one for a subordinate character like Ferrando. But in "Il Trovatore" Verdi is lavish with his melodies -- more so perhaps, than in any of his other operas.

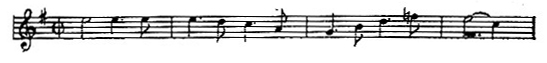

The scene changes to the gardens of the palace. On one side a flight of marble steps leads to Leonora’s apartment. Heavy clouds obscure the moon. Leonora and Inez are in the garden. From the confidante’s questions and Leonora’s answers it is gathered that Leonora is enamoured of an unknown but valiant knight who, lately entering a tourney, won all contests and was crowned victor by her hand. She knows her love is requited, for at night she has heard her Troubadour singing below her window. In the course of this narrative Leonora has two solos. The first of these is the romantic "Tacea la notte placida" (The night calmly and peacefully in beauty seemed reposing).

It is followed by the graceful and engaging "Di tale amor che dirsi" (Of such a love how vainly),

with its brilliant cadenza.

Leonora and Inez then ascend the steps and retire into the palace. The Count di Luna now come sinto the garden. He has hardly entered before the voice of the troubadour, accompanied on a lute, is heard from a nearby thicket singing the familiar romanza, "Deserto sulla terra" (Lonely on earth abiding).

From the palace comes Leonora. Mistaking the Count in the shadow of the trees for her Troubadour, she hastens toward him. The moon emerging from a cloud, she sees the figure of a masked cavalier, recognizes it as that of her lover, and turns from the Count toward the Troubadour. Unmasking, the Troubadour now discloses his identity as Manrico, one who, as a follower of the Prince of Biscay, is proscribed in Aragon. The men draw their swords. There is a trio that fairly seethes with passion -- "Di geloso amor spezzato" (Fires of jealous, despised affection).

These are the words, in which the Count begins the trio. It continues with "Un istante almen dia loco" (One brief moment thy fury restraining).

The men rush off to fight their duel. Leonora faints.

Act II. An encampment of gypsies. There is a ruined house at the foot of a mountain in Biscay, the interior partly exposed to view; within a great fire is lighted. Day begins to dawn.

Azucena is seated near the fire. Manrico, enveloped in his mantle, is lying upon a mattress; his helmet is at his feet; in his hand he holds a sword, which he regards fixedly. A band of gypsies are sitting in scattered groups around them.

Since an almost unbroken sequence of melodies is a characteristic of "Il Trovatore," it is not surprising to find at the opening of this act two famous numbers in quick succession; -- the famous "Anvil Chorus,"

in which the gypsies, working at the forges, swing their hammers and bring them down on clanking metal in rhythm with the music, the chorus being followed immediately by Azucena’s equally famous "Stride la vampa" (Upward the flames roll).

In this air, which the old gypsy woman sings as a weird, but impassioned upwelling of memories and hatreds, while the tribe gathers about her, she relates the story of her mother’s death. "Avenge thou me!" she murmurs to Manrico, when she has concluded.

The corps de ballet which, in the absence of a regular ballet in "Il Trovatore," utilizes this scene and the music of the "Anvil Chorus" for its pictureque saltations, dances off. The gypsies now depart, singing their chorus. With a pretty effect it dies away in the distance.

Swept along by the emotional stress under which she labours, Azucena concludes her narrative of the tragic events at the pyre, voice and orchestral accompaniment uniting in a vivid musical setting of her memories. Naturally, her words arouse doubts in Manrico’s mind as to whether he really is her son. She hastens to dispel these; they were but wandering thoughts she uttered. Moreover, after the recent battle of Petilla, between the forces of Biscay and Aragon, when he was reported slain, did she not search for and find him, and has she not been tenderly nursing him back to strength?

The forces of Aragon were led by Count di Luna, who but a short time before had been overcome by Manrico in a duel in the palace garden; -- why, on that occasion, asks the gypsy, did he spare the Count’s life?

Manrico’s reply is couched in a bold, martial air, "Mal reggendo all’ aspro assalto" (Ill sustaining the furious encounter).

But at the end it dies away to pianissimo, when he tells how, when the Count’s life was his for a thrust, a voice as if from heaven, bade him spare it -- a suggestion, of course, that although neither Manrico nor the Count that they are brothers, Manrico unconsciously was swayed by the relationship, a touch of psychology rare in Italian opera librettos, most unexpected in this, and, of course, completely lost upon those who have not familiarized themselves with the plot of "Il Trovatore." Incidentally, however, it accounts for a musical effect-the pianissimo, the sudden softening of the expression, at the end of the martial description of the duel.

Enter now Ruiz, a messenger from the Prince of Biscay, who orders Manrico to take command of the forces defending the stronghold of Castellor, and at the same time informs him that Leonora, believing reports of his death at Petilla, is about to take the veil in a convent near the castle.

The scene changes to the cloister of this convent. It is night. The Count and his followers, led by Ferrando, and heavily cloaked, advance cautiously. It is the Count’s plan to carry off Leonora before she becomes a nun. He sings of his love for her in the air, "Il Balen" (The Smile)- "Il balen del suo sorriso" (Of her smile, the radiant gleaming) -- which is justly regarded as one of the most chaste and beautiful baritone solos in Italian opera.

It is followed by an air alla marcia, also for the Count, "Per me ora fatale" (Oh, fatal hour impending)

A chorus of nuns is heard from within the convent. Leonora, with Inez, and her ladies, come upon the scene. They are about to proceed from the cloister into the convent when the Count interposes. But before he can seize Leonora, another figure stands between them. It is Manrico. With him are Ruiz and his followers. The Count is foiled.

"E deggio! -- e posso crederlo?" (And can I still my eyes believe!) exclaims Leonora, as she beholds before her Manrico, whom she had thought dead. It is here that begins the impassioned finale, an ensemble consisting of a trio for Leonora, Manrico, and the Count di Luna, with chorus.

Act III. The camp of Count di Luna, who is laying siege to Castellor, whither Manrico has safety borne Leonora. There is a stirring chorus for Ferrando and the soldiers.

The Count comes from his tent. He casts a lowering gaze at the stronghold from where his rival defies him. There is a commotion. Soldiers have captured a gypsy woman found prowling about the camp. They drag her in. She is Azucena. Questioned, she sings that she is a poor wanderer, who means no harm. "Giorni poveri vivea" (I was poor, yet uncomplaining).

But Ferrando, though she thought herself masked by the grey hairs and wrinkles of age, recognizes her as the gypsy who, to avenge her mother, gave over the infant brother of the Count to the flames. In the vehemence of her denials, she cries out to Manrico, whom she names as her son, to come to her rescue. This still further enrages the Count. He orders that she be cast into prison and then burned at the stake. She is dragged away.

The scene changes to a hall adjoining the chapel in the stronghold of Castellor. Leonora is about to become the bride of Manrico, who sings the beautiful lyric, "Amor-sublime amore" (‘Tis love, sublime emotion).

Its serenity makes all the more effective the tumultuous scene that follows. It assists in giving to that episode, one of the most famous in Italian opera, its true significance as a dramatic climax.

Just as Manrico takes Leonora’s hand to lead her to the altar of the chapel, Ruiz rushes in with word that Azucena has been captured by the besiegers and is about to be burned to death. Already through the windows of Castellor the glow of flames can be seen. Her peril would render delay fatal. Dropping the hand of his bride, Manrico, draws his sword, and, as his men gather, sings "Di quella pira ‘l’orrendo foco" (See the pyre blazing, oh, sight of horror), and rushes forth at the head of his soldiers to attempt to save Azucena.

The line, "O teco almeno, corro a morir" (Or, all else failing, to die with thee), contains the famous high C.

This is a tour de force, which has been condemned as vulgar and ostenatious, but which undoubtedly adds to the effectiveness of the number. There is, it should be remarked, no high C in the score of "Di quella pira." In no way is Verdi responsible for it. It was introduced by a tenor, who saw a chance to make an effect with it, and succeeded so well that it became a fixture. A tenor now content to sing "O teco almeno" as Verdi wrote it

would never be asked to sing it.

Dr. Frank E. Miller, author of The Voice and Vocal Art Science, the latter the most complete exposition of the psycho-physical functions involved in voice-production, informs me that a series of photographs have been made (by an apparatus too complicated to describe) of the vibrations of Caruso’s voice as he takes and holds the high C in "Di quella pira." The record measures fifty-eight feet. While it might not be correct to say that Caruso’s high C is fifty-eight feet long, the record is evidence of its being superbly taken and held.

Not infrequently the high C in "Di quella pira" is faked for tenors who cannot reach it, yet have to sing the role of Manrico, or who, having been able to reach it in their younger days and at the height of their prime, still wish to maintain their fame as robust tenors. For such the number is transposed. The tenor, instead of singing high C, sings B flat, a tone and a half lower, and much easier to take. By flourishing his sword and looking very fierce he usually manages to get away with it. Transpositions of operatic airs, requiring unusually high voices, are not infrequently made for singers, both male and female, no longer in their prime, but still good for two or three more "farewell" tours. All they have to do is to step up to the footlights with an air of perfect confidence, which indicates that the great moment in the performance has arrived, deliver, with a certain assumption of effort -- the semblance of a real tour de force -- the note which has conveniently been transposed, and receive the enthusiastic plaudits of their devoted admirers. But the assumption of effort must not be omitted. The tenor who sings the high C in "Di quella pira" without getting red in the face will hardly be credited with having sung it at all.

Act IV. Manrico’s sortie to rescue his supposed mother failed. His men were repulsed, and he himself was captured and thrown into the dungeon tower of Aliaferia, where Azucena was already enchained. The scene shows a wing of the palace of Aliaferia. In the angle is a tower with window secured by iron bars. It is night, dark and clouded.

Leonora enters with Ruiz who points out to her the place of Manrico’s confinement, and retires. That she has conceived a desperate plan to save her lover appears from the fact that she wears a poison ring, a ring with a swift poison concealed under the jewel, so that she can take her own life, if driven thereto.

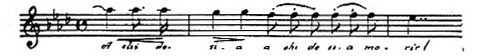

Unknown to Manrico, she is near him. Her thoughts wander to him; -- "D’amor sull ali rosee" (On rosy wings of love depart).

It is followed by the "Miserere," which was for many years and perhaps still is the world over the most popular of all melodies from opera, although at the present time it appears to have been superseded by the "Intermezzo" from "Cavalleria Rusticana."

The "Miserere" is chanted by a chorus within.

Against this as a sombre background are projected the heart-broken ejaculations of Leonora.

Then Manrico’s voice in the tower intones "Ah! che la morte ognora" (Ah! how death still delayeth).

One of the most characteristic phrases, suggestions of which occur also in "La Traviata" and even in "Aida," is the following:

Familiarity may breed contempt, and nothing could well be more familiar than the "Miserere" from "Il Trovatore." Yet, well sung, it never fails of effect; and the gaoler always has to let Manrico come out of the tower and acknowledge the applause of an excited house, while Leonora stands by and pretends not to see him, one of those little fictions and absurdities of old-fashioned opera that really add to its charm.

The Count enters, to be confronted by Leonora. She promises to become his wife if he will free Manrico. Di Luna’s passion for her is so intense that he agrees. There is a solo for Leonora, "Mira, di acerbe lagrime" (Witness the tears of agony), followed by a duet between her and the Count who little suspects that, Manrico once freed, she will escape a hated union with himself by taking the poison in her ring.

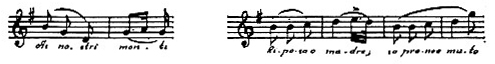

The scene changes to the interior of the tower. Manrico and Azucena sing a duet of mournful beauty, "Ai nostri monti" (Back to our mountains).

Leonora enters and bids him escape. But he suspects the price she has paid; and his suspicious are confirmed by herself, when the poison she has drained from beneath the jewel in her ring begins to take effect and she feels herself sinking in death, while Azucena, in her sleep, croons dreamily, "Back to our mountains."

The Count di Luna, coming upon the scene, finds Leonora dead in her lover’s arms. He orders Manrico to be led to the block at once and drags Azucena to the window to witness the death of her supposed son.

"It is over!" exclaims Di Luna, when the executioner has done his work.

"The victim was thy brother!" shrieks the gypsy hag. "Thou art avenged, O mother!"

She falls near the window.

"And I still live!" exclaims the Count.

With that exclamation the cumulative horrors, set to the most tuneful score in Italian opera, are over.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-25 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |