Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > Tristan und Isolde (Wagner) - Synopsis

Tristan und Isolde - Synopsis

(English title: Tristan and Isolde)

An Opera by Richard Wagner

CHARACTERS

TRISTAN, a Cornish knight, nephew to KING MARKE……… Tenor

KING MARKE, of Cornwall………………………………………. Bass

ISOLDE, an Irish princess……………………………………… Soprano

KURWENAL, one of TRISTAN’S retainers………………….. Baritone

MELOT, a courtier……………………………………….….…. Baritone

BRANGANE, ISOLDE’S attendant………………………….. Mezzo-Soprano

A SHEPHERD………………………………………………… Tenor

A SAILOR…………………………………………………….. Tenor

A HELMSMAN………………………………………………. Baritone

Sailors, Knights, Esquires, and Men-at-Arms.

Time: Legendary.

Place: A ship at sea; outside King Marke’s palace, Cornwall; the platform at Kareol, Tristan’s castle.

Wagner was obliged to remodel the "Tristan" legend thoroughly before it became available for a modern drama. He has shorn it of all unnecessary incidents and worked over the main episodes into a concise, vigorous, swiftly moving drama, admirably adapted for the stage. He shows keen dramatic insight in the manner in which he adapts the love-potion of the legends to his purpose. In the legends the love of Tristan and Isolde is merely "chemical" -- entirely the result of the love-philtre. Wagner, however, presents them from the outset as enamoured of one another, so that the potion simply quickens a passion already active.

In the Wagnerian version the plot is briefly as follows: Tristan, having lost his parents in infancy, has been reared at the court of his uncle, Marke, King of Cornwall. He has slain in combat Morold, an Irish knight, who had come to Cornwall, to collect the tribute that country had been paying to Ireland. Morold was affianced to his cousin Isolde, daughter of the Irish king. Tristan, having been dangerously wounded in the combat, places himself, without disclosing his identity, under the care of Morold’s affianced, Isolde who comes of a race skilled in magic arts. She discerns who he is; but, although she is aware that she is harbouring the slayer of her affianced, she spares him and carefully tends him, for she has conceived a deep passion for him. Tristan also becomes enamoured of her, but both deem their love unrequited. Soon after Tristan’s return to Cornwall, he is dispatched to Ireland by Marke, that he may win Isolde as Queen for the Cornish king.

The music-drama opens on board the vessel in which Tristan bears Isolde to Cornwall. Deeming her love for Tristan unrequited she determines to end her sorrow by quaffing a death-potion; and Tristan, feeling that the woman he loves is about to be wedded to another, readily consents to share it with her. But Brangäne, Isolde’s companion, substitutes a love-potion for the death-draught. This rouses their love to resistless passion. Not long after they reach Cornwall, they are surprised in the castle garden by the King and his suite, and Tristan is severely wounded by Melot, one of Marke’s knights. Kurwenal, Tristan’s faithful retainer, bears him to his native place, Kareol. Hither Isolde follows him, arriving in time to fold him in her arms as he expires. She breathes her last over his corpse.

THE VORSPIEL

All who have made a study of opera, and do not regard it merely as a form of amusement, are agreed that the score of "Tristan and Isolde" is the greatest setting of a love story for the lyric stage. In fact to call it a love-story seems a slight. It is a tale of tragic passion, culminating in death, unfolded in the surge and palpitation of immortal music.

This passion smouldered in the heart of the man and woman of this epic of love. It could not burst into clear flame because over it lay the pall of duty -- a knight’s to his king, a wife’s to her husband. They elected to die; drank, as they thought, a death potion. Instead it was a magic love-philtre, craftily substituted by the woman’s confidante. Then love, no longer, vague and hesitating, but roused by sorcerous means to the highest rapture, found expression in the complete abandonment of the lovers to their ecstasy -- and their fate.

What precedes the draught of the potion in the drama, is narrative, explanatory and prefatorial. Once Tristan and Isolde have shared the goblet, passion is unleashed. The goal is death.

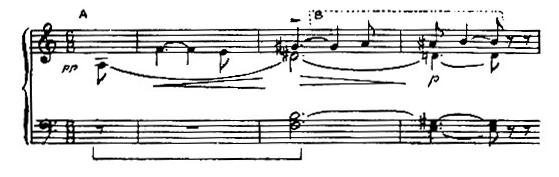

The magic love-philtre is the excitant in this story of rapture and gloom. The Vorspiel therefore opens most fittingly with a motive which expresses the incipient effect of the potion upon Tristan and Isolde. It clearly can be divided into two parts, one descending, the other ascending chromatically. The potion overcomes the restraining influence of duty in two beings and leaves them at the mercy of their passions. The first part, with its descending chromatics, is pervaded by a certain trist mood, as if Tristan were still vaguely forewarned by his conscience of the impending tragedy. The second soars ecstatically upward. It is the woman yielding unquestioningly to the rapture of requited love. Therefore, while the phrase may be called the Motive of the Love-Potion, or, as Wolzogen calls it, of Yearning, it seems best to divide it into the Tristan and Isolde Motives (A and B).

The two motives having been twice repeated, there is a fermate. Then the Isolde Motive alone is heard, so that the attention of the hearer is fixed upon it. For in this tragedy, as in that of Eden, it is the woman who takes the first decisive step. After another fermate, the last two notes of the Isolde Motive are twice repeated, dying away to pianissime. Then a variation of the Isolde Motive leads

with an impassioned upward sweep into another version. Full of sensuous yearning, and distinct enough to form a new motive, the Motive of the Love Glance.

This occurs again and again in the course of the Vorspiel. Though readily recognized, it is sufficiently varied with each repetition never to allow the emotional excitement to subside. In fact, the Vorspiel gathers impetus as it proceeds, until, with an inversion of the Love Glance Motive, borne to a higher and higher level of exaltation by upward rushing runs, it reaches its climax in a paroxysm

of love, to die away with repetitions of the Tristan, the Isolde, and the Love Glance motives.

In the themes it employs this prelude tells, in music, the story of the love of Tristan and Isolde. We have the motives of the hero and heroine of the drama, and the Motive of the Love Glance. When as is the case in concerts, the finale of the work, "Isolde’s Love-Death," is linked to the Vorspiel, we are entrusted with the beginning and the end of the music-drama, forming an eloquent epitome of the tragic story.

Act I. Wagner wisely refrains from actually placing before us on the stage, the events that transpired in Ireland before Tristan was dispatched thither to bring Isolde as a bride to King Marke. The events, which led to the two meetings between Tristan and Isolde, are told in Isolde’s narrative, which forms an important part of the first act. This act opens aboard the vessel in which Tristan is conveying Isolde to Cornwall.

The opening scene shows Isolde reclining on a couch, her face hid in soft pillows, in a tent-like apartment on the forward deck of a vessel. It is hung with rich tapestries, which hide the rest of the ship from view. Brangäne has partially drawn aside one of the hangings and is gazing out upon the sea. From above, as though from the rigging, is heard the voice of a young Sailor singing a farewell song to his "Irish maid." It has a wild charm and is a capital example of Wagner’s skill in giving local colouring to his music. The words, "Frisch weht der Wind der Heimath zu" (The wind blows freshly toward our home) are sung to a phrase which occurs frequently in the course of this scene. It represents most graphically the heaving of the sea and may be appropriately termed the Ocean Motive. It undulates gracefully through Brangäne’s reply to Isolde’s question as to the vessel’s course, surges wildly around Isolde’s outburst of impotent anger when she learns that Cornwall’s shore is not far distant, and breaks itself in savage fury against her despairing wrath as she invokes the elements to destroy the ship and all upon it. Ocean Motive.

It is her hopeless passion for Tristan which has prostrated Isolde, for the Motive of the Love Glance accompanies her first exclamation as she starts up excitedly.

Isolde calls upon Brangäne to throw aside the hangings, that she may have air. Brangäne obeys. The deck of the ship, and, beyond it, the ocean, are disclosed. Around the mainmast sailors are busy splicing ropes. Beyond them, on the after deck, are knights and esquires. A little aside from them stands Tristan, gazing out upon the sea. At his feet reclines Kurwenal, his esquire. The young sailor’s voice is again heard.

Isolde beholds Tristan. Her wrath at the thought that he whom she loves is bearing her as bride to another vents itself in a vengeful phrase. She invokes death upon him. This phrase is the Motive of Death.

The Motive of the Love Glance is heard -- and gives away Isolde’s secret -- as she asks Brangäne in what estimation she holds Tristan. It develops into a triumphant strain as Brangäne sings his praises. Isolde then bids her command Tristan to come into her presence. This command is given with the Motive of Death, for it is their mutual death Isolde wishes to compass. As Brangäne goes to do her mistress’s bidding, a graceful variation of the Ocean Motives is heard, the bass marking the rhythmic motions of the sailors at the ropes. Tristan refuses to leave the helm and when Brangäne repeats Isolde’s command, Kurwenal answers in deft measures in praise of Tristan. Knights, esquires, and sailors repeat the refrain. The boisterous measures -- "Hail to our brave Tristan!" -- form the Tristan Call.

Isolde’s wrath at Kurwenal’s taunts find vent in a narrative in which she tells Brangäne that once a wounded knight calling himself Tantris landed on Ireland’s shore to seek her healing art. Into a niche in his sword she fitted a sword splinter she had found imbedded in the head of Morold, which had been sent to her in mockery after he had been slain in a combat with the Cornish foe. She brandished the sword over the knight, whom thus by his weapon she knew to be Tristan, her betrothed’s slayer. But Tristan’s glance fell upon her. Under its spell she was powerless. She nursed him back to health, and he vowed eternal gratitude as he left her. The chief theme of this narrative is derived from Tristan Motive.

What of the boat, so bare, so frail,

That drifted to our shore?

What of the sorely stricken man feebly extended there?

Isolde’s art he humbly sought;

With balsam, herbs, and healing salves,

From wounds that laid him low,

She nursed him back to strength.

Exquisite is the transition of the phrase "His eyes in mine were gazing," to the Isolde and Love Glance motives. The passage beginning: "Who silently his life had spared," is followed by the Tristan Call, Isolde seeming to compare sarcastically what she considers his betrayal of her with his fame as a hero. Her outburst of wrath as she inveighs against his treachery in now bearing her as bride to King Marke, carries the narrative to a superb climax. Brangäne seeks to comfort Isolde, but the latter, looking fixedly before her, confides, almost involuntarily, her love for Tristan.

It is clear, even from this brief description, with what constantly varying expression the narrative of Isolde is treated. Wrath, desire for vengeance, rapturous memories that cannot be dissembled, finally a confession of love to Brangäne -- such are the emotions that surge to the surface.

They lead Brangäne to exclaim: "Where lives the man who would not love you?" Then she weirdly whispers of the love-potion and takes a phial from a golden salver. The motives of the Love Glance and of the Love-Potion accompany her words and action. But Isolde seizes another phial, which she holds up triumphantly. It is the death-potion. Here is heard an ominous phrase of three notes -- the Motive of Fate.

A forceful orchestral climax, in which the demons of despairing wrath seem unleased, is followed by the cries of the sailors greeting the sight of the land, where she is to be married to King Marke. Isolde hears them with growing terror. Kurwenal brusquely calls to her and Brangäne to prepare soon to go ashore. Isolde orders Kurwenal that he command Tristan to come into her presence; then bids Brangäne prepare the death-potion. The Death Motive accompanies her final commands to Kurwenal and Brangäne, and the Fate Motive also drones threatfully through the weird measures. But Brangäne artfully substitutes the love-potion for the death-draught.

Kurwenal announces Tristan’s approach. Isolde, seeking to control her agitation, strides to the couch, and, supporting herself by it, gazes fixedly at the entrance where Tristan remains standing. The motive which announces his appearance is full of tragic defiance, as if Tristan felt that he stood upon the threshold of death, yet was ready to meet this fate unflinchingly. It alternates effectively with the Fate Motive, and is used most dramatically throughout the succeeding scene between Tristan and Isolde. Sombrely impressive is the passage when he bids Isolde slay him with the sword she once held over him.

If so thou didst love thy lord,

Lift once-again this sword,

Thrust with it, nor refrain,

Lest the weapon fall again.

Shouts of the sailors announce the proximity of land. In a variant of her narrative theme Isolde mockingly anticipates Tristan’s praise of her as he leads her into King Marke’s presence. At the same time she hands him the goblet which contains, as she thinks, the death-potion and invites him to quaff it. Again the shouts of the sailors are heard, and Tristan, seizing the goblet, raises it to his lips with the ecstasy of one from whose soul a great sorrow is about to be lifted. When he has half emptied it, Isolde wrests it from him and drains it.

The tremor that passes over Isolde loosens her grasps upon the goblet. It falls from her hand. She faces Tristan.

Is the weird light in their eyes the last upflare of passion before the final darkness? What does the music answer as it enfolds them in its wondrous harmonies? The Isolde Motive;-then what? Not the glassy stare of death; the Love Glance, like a swift shaft of light penetrating the gloom. The spell is broken. Isolde sinks into Tristan’s embrace.

Voices! They hear them not. Sailors are shouting with joy that the voyage is over. Upon the lovers all sounds are lost, save their own short, quick interchange of phrases, in which the rapture of their passion, at last uncovered, finds speech. Music surges about them. But for Brangäne they would be lost. It is she who parts them, as the hangings are thrust aside.

Knights, esquires, sailors crowd the deck. From a rocky height King Marke’s castle looks down upon the ship, now riding at anchor in the harbour. Peace and joy everywhere save in the lovers’ breasts! Isolde faints in Tristan’s arms. Yet it is a triumphant climax of the Isolde Motive that is heard above the jubilation of the ship-folk, as the act comes to a close.

Act II. This act also has an introduction, which together with the first scene between Isolde and Brangäne, constitutes a wonderful mood picture in music. Even Wagner’s bitterest critic, Edward Hanslick, of Vienna, was forced to compare it with the loveliest creations of Schubert, in which that composer steeps the senses in dreams of night and love.

And so, this introduction of the second act opens with a motive of peculiar significance. During the love scene in the previous act, Tristan and Isolde have inveighed against the day which jealousy keeps them apart. They may meet only under the veil of darkness. Even then their joy is embittered by the thought that the blissful night will soon be succeeded by day. With them, therefore, the day stands for all that is inimical, night for all that is friendly. This simile is elaborated with considerable metaphysical subtlety, the lovers even reproaching the day with Tristan’s willingness to lead Isolde to King Marke, Tristan charging that in the broad light of the jealous day his duty to win Isolde for his kind stood forth so clearly as to overpower the passion for her which he had nurtured during the silent watches of the night. The phrase, therefore, which begins the act as with an agonized cry is the Day Motive.

The Day Motive is followed by a phrase whose eager, restless measures graphical reflect the impatience with which Isolde awaits the coming of Tristan -- the Motive of Impatience.

Over this there hovers a dulcet, seductive strain, the Motive of the Love Call, which is developed into the rapturous measures of the Motive of Ecstasy.

When the curtains rises, the scene it discloses is the palace garden, into which Isolde’s apartments open. It is a summer night, balmy and with a moon. The King and his suite have departed on a hunt. With them is Melot, a knight who professes devotion to Tristan but whom Brangäne suspects.

Brangäne stands upon the steps leading to Isolde’s apartment. She is looking down a bosky allee in the direction taken by the hunt. This silently gliding, uncanny creature, the servitor of sin in others, is uneasy. She fears the hunt is but a trap; and that its quarry is not the wild deer, but her mistress and the knight, who conveyed her for bride to King Marke.

Meanwhile against the open door of Isolde’s apartment is a burning torch. Its flare through the night is to be the signal to Tristan that all is well, and that Isolde waits.

The first episode of the act is one of these exquisite tone paintings in the creation of which Wagner is supreme. The notes of the hunting-horns become more distant. Isolde enters from her apartment into the garden. She asks Brangäne if she cannot now signal for Tristan. Brangäne answers that the hunt is still within hearing. Isolde chides her -- is it not some lovely, prattling rill she hears? The music is deliciously idyllic -- conjuring up a dream-picture of a sylvan spring night bathed in liquescent moonlight. Brangäne warns Isolde against Melot; but Isolde laughs at her fears. In vain Brangäne entreats her mistress not to signal for Tristan. The seductive measures of the Love Call and of the Motive of Ecstasy tell throughout this scene of the yearning in Isolde’s breast. When Brangäne informs Isolde that she substituted the love-potion for the death-draught, Isolde scorns the suggestion that her guilty love for Tristan is the result of her quaffing the potion. This simply intensified the passion already in her breast. She proclaims this in the rapturous phrases of the Isolde Motive; and then, when she declares her fate to be in the hands of the goddess of love, there are heard the tender accents of the Love Motive.

In vain Brangäne warns once more against possible treachery from Melot. The Love Motive rises with ever increasing passion until Isolde’s emotional exaltation finds expression in the Motive of Ecstasy as she bids Brangäne hie to the lookout, and proclaims that she will give Tristan the signal by extinguishing the torch, though in doing so she were to extinguish the light of her life. The Motive of the Love Call ringing out triumphantly accompanies her action, and dies away into the Motive of Impatience as she gazes down a bosky avenue through which she seems to expect Tristan to come to her. Then the Motives of Ecstasy and Isolde’s rapturous gesture tell that she has discerned her lover; and, as this Motive reaches a fiercely impassioned climax. Tristan and Isolde rush into each other’s arms.

The music fairly seethes with passion as the lovers greet one another, the Love Motive and the Motive of Ecstasy vying in the excitement of this rapturous meeting. Then begins the exchange of phrases in which the lovers pour forth their love for one another. This is the scene dominated by the Motive of the Day, which, however, as the day sinks into the soft night, is softened into the Night Motive, which soothes the senses with its ravishing caress.

This motive throbs through the rapturous harmonies of the duet" "Oh, sink upon us, Night of Love," and there is nothing in the realms of music or poetry to compare in suggestiveness with these caressing, pulsating phrases.

The duet is broken in upon by Brangäne’s voice warning the lovers that night will soon be over. The arpeggios accompanying her warning are like the first grey streaks of dawn. But the lovers heed her not. In a smooth, soft melody -- the Motive of Love’s Peace -- whose sensuous grace is simply entrancing, they whisper their love.

It is at such a moment, enveloped by night and love, that death should have come to them, and, indeed, it is for such a love-death they yearn. Hence we have here, over a quivering accompaniment, the Motive of the Love-Death.

Once more Brangäne calls. Once more Tristan and Isolde heed her not.

Night will shield us for aye!

Thus exclaims Isolde in defiance of the approach of dawn, while the Motive of ecstasy, introduced by a rapturous mordent, soars ever higher.

A cry from Brangäne, Kurwenal rushing upon the scene calling to Tristan to save himself -- and the lovers’ ravishing dream is ended. Surrounded by the King and his suite, with the treacherous Melot, they gradually awaken to the terror of the situation. Almost automatically Isolde hides her head among the flowers, and Tristan spreads out his cloak to conceal her from view while phrases reminiscent of the love scene rise like mournful memories.

Now follows a soliloquy for the King, whose sword instead should have leapt from its scabbard and buried itself in Tristan’s breast. For it seems inexplicable that the monarch, who should have slain the betrayer of his honour, indulges instead in a philosophical discourse, ending:

The unexplained

Unpenetrated

Cause of all these woes,

Who will to us disclose?

Tristan turns to Isolde. Will she follow him to the bleak land of his birth? Her reply is that his home shall be her’s. Then Melot draws his sword. Tristan rushes upon him, but as Melot thrusts, allows his guard to fall and receives the blade. Isolde throws herself on her wounded lover’s breast.

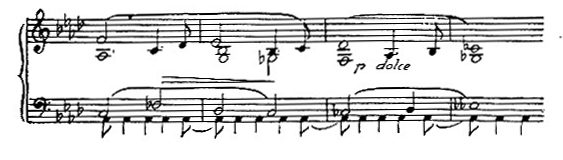

Act III. The introduction to this act opens with a variation of the Isolde Motive, sadly prophetic of the desolation which broods over the scene to be disclosed when the curtain rises. On its third repetition it is continued in a long-drawn-out ascending phrase, which seems to represent musically the broad waste of ocean upon which Tristan’s castle looks down from its craggy height.

The whole passage appears to represent Tristan hopelessly yearning for Isolde, letting his fancy travel back over the watery waste to the last night of love, and then giving himself up wholly to his grief.

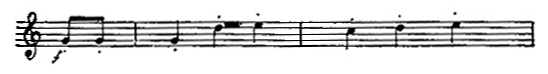

The curtain rises upon the desolate grounds of Kareol, between the outer walls of Tristan’s castle and the main structure, which stands upon a rocky eminence overlooking the sea. Tristan is stretched, apparently lifeless, under a huge linden-tree. Over him, in deep sorrow, bends the faithful Kurwenal. A Shepherd is heard piping a strain, whose plaintive notes harmonize most beautifully with the despairing desolation and sadness of the scene. It is the Lay of Sorrow, and by it, the Shepherd who scans the sea, conveys to Kurwenal information that the ship he has dispatched to Cornwall to bear Isolde to Kareol has not yet hove in sight.

The Lay of Sorrow is a strain of mournful beauty, with the simplicity and indescribable charm of a folk-song. Its plaintive notes cling like ivy to the grey and crumbling ruins of love and joy.

[Music excerpt]

The Shepherd peers over the wall and asks if Tristan has shown any signs of life. Kurwenal gloomily replies in the negative. The Shepherd departs to continue his lookout, piping the sad refrain. Tristan slowly opens his eyes. "The old refrain; why wakes it me? Where am I?" he murmurs. Kurwenal is beside himself with joy at these signs of returning life. His replies to Tristan’s feeble and wandering questions are mostly couched in a motive which beautifully expresses the sterling nature of this faithful retainer, one of the noblest characters Wagner has drawn.

When Tristan loses himself in sad memories of Isolde, Kurwenal seeks to comfort him with the news that he has sent a trusty man to Cornwall to bear Isolde to him that she may heal the wound inflicted by Melot as she once healed that dealt Tristan by Morold. In Tristan’s jubilant reply, during which he draws Kurwenal to his breast, the Isolde Motive assumes a form in which it becomes a theme of joy.

But it is soon succeeded by the Motive of Anguish,

when Tristan raves of his yearning for Isolde. "The ship! the ship!" he exclaims. "Kurwenal, can you not see it?" The Lay of Sorrow, piped by the Shepherd, gives the sad answer. It pervades his sad reverie until, when his mind wanders back to Isolde’s tender nursing of his wound in Ireland, the theme of Isolde’s Narrative is heard again. Finally his excitement grows upon him, and in a paroxysm of anguish bordering on insanity he even curses love.

Tristan sinks back apparently lifeless. But no -- as Kurwenal bends over him and the Isolde Motive is breathed by the orchestra, he again whispers of Isolde. In ravishing beauty the Motive of Love’s Peace caressingly follows his vision as he seems to see Isolde gliding toward him o’er the waves. With ever-growing excitement he orders Kurwenal to the lookout to watch the ship’s coming. What he sees so clearly cannot Kurwenal also see? Suddenly the music changes in character. The ship is in sight, for the Shepherd is heard piping a joyous lay. It pervades the music of

Tristan’s excited questions and Kurwenal’s answer as to the vessel’s movements. The faithful retainer rushed down toward the shore to meet Isolde and lead her to Tristan. The latter, his strength sapped by his wound, his mind inflamed to insanity by his passionate yearning, struggles to rise. He raises himself a little. The Motive of Love’s Peace, no longer tranquil, but with frenzied rapidity, accompanies his actions as, in his delirium, he tears the bandage from his wounds and rises from his couch.

Isolde’s voice! Into her arms, outstretched to receive him, staggers Tristan. Gently she lets him down upon his couch, where he has lain in the anguish of expectancy.

"Tristan!"

"Isolde!" he answers in broken accents. This last look resting rapturously upon her, while in mournful beauty the Love-Glance Motive rises from the orchestra, he expires.

In all music there is no scene more deeply shaken with sorrow.

Tumultuous sounds are heard. A second ship has arrived. Marke and his suite have landed. Tristan’s men, thinking the King has come in pursuit of Isolde, attack the new-comers, Kurwenal and his men are overpowered, and Kurwenal, having avenged Tristan by slaying Melot, sinks, himself mortally wounded, dying by Tristan’s side. He reaches out for his dead master’s hand, and his last words are: "Tristan, chide me not that faithfully I follow you."

When Brangäne rushes in and hurriedly announces that she has informed the King of the love-potion, and that he comes bringing forgiveness, Isolde heeds her not. As the Love-Death Motive rises softly over the orchestra and slowly swells into the impassioned Motive of Ecstasy, to reach its climax with a stupendous crash of instrumental forces, she gazes with growing transport upon her dead lover, until, with rapture in her last glance, she sinks upon his corpse and expires.

In the Wagnerian version of the legend this love-death for which Tristan and Isolde prayed and in which they are united, is more than a mere farewell together to life. It is tinged with Oriental philosophy, and symbolizes the taking up into and the absorption of by nature of all that is spiritual, and hence immortal, in lives rendered beautiful by love.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-25 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |