Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > Siegfried (Wagner) - Synopsis

Siegfried - Synopsis

An Opera by Richard Wagner

CHARACTERS

SIEGFRIED………………………….. Tenor

MIME……………………………….. Tenor

WOTAN (disguised as the WANDERER).. Baritone-Bass

ALBERICH………………………….. Baritone-Bass

FAFNER……………………………… Bass

ERDA………………………………… Contralto

FOREST BIRD………………………. Soprano

BRUNNHILDE………………………. Soprano

Time: Legendary.

Place: A rocky cave in the forest; deep in the forest; wild region at foot of a rocky mount; the Brünnhilde-rock.

The Nibelungs were not present in the dramatic action of "The Valkyr," though the sinister influence of Alberich shaped the tragedy of Siegmund’s death. In "Siegfried" several characters of "The Rhinegold," who do no take part in "The Valkyr," reappear. These are the Nibelungs Alberich and Mime; the giant Fafner, who in the guise of a serpent guards the Ring, the Tarnhelmet, and the Nibelung hoard in a cavern, and Erda.

Siegfried has been born of Sieglinde, who died in giving birth to him. This scion of the Wälsung race has been reared by Mime, who found him in the forest by his dead mother’s side. Mime is plotting to obtain possession of the ring and of Fafner’s other treasurers, and hopes to be aided in his designs by the lusty youth. Wotan, disguised as a wanderer, is watching the course of events, again hopeful that a hero of the Wälsung race will free the gods from Alberich’s curse. Surrounded by magic fire, Brünnhilde still lies in deep slumber on the Brünnhilde Rock.

The Vorspiel of "Siegfried" is expressive of Mime’s planning and plotting. It begins with music of a mysterious brooding character. Mingling with this is the Motive of the Hoard, familiar from "The Rhinegold." Then is heard the Nibelung Motive. After reaching a forceful climax it passes over to the Motive of the Ring, which rises from pianissimo to a crashing climax. The ring is to be the prize of all Mime’s plotting. He hopes to weld the pieces of Siegmund’s sword together, and that with this sword Siegfried will slay Fafner. Then Mime will slay Siegfried and possess himself of the ring. Thus it is to serve his own ends only, that Mime is craftily rearing Siegfried.

The opening scene shows Mime forging a sword at a natural forge formed in a rocky cave. In a soliloquy he discloses the purpose of his labours and laments that Siegfried shivers every sword which has been forged for him. Could he (Mime) but unite the pieces of Siegmund’s sword! At this thought the Sword Motive rings out brilliantly, and is jubilantly repeated, accompanied by a variant of the Walhalla Motive. For if the pieces of the sword were welded together, and Siegfried were with it to slay Fafner, Mime could surreptitiously obtain possession of the ring, slay Siegfried, rule over the gods in Walhalla, and circumvent Alberich’s plans for regaining the hoard.

Mime is still at work when Siegfried enters, clad in a wild forest garb. Over it a silver horn is slung by a chain. The sturdy youth has captured a bear. He leads it by a vast rope, with which he gives it full play so that it can make a dash at Mime. As the latter flees terrified behind the forge, Siegfried gives vent to his high spirits in shouts of laughter. Musically his buoyant nature is expressed by a theme inspired by the fresh, joyful spirit of a wild, woodland life. It may be called, to distinguish it from the Siegfried Motive, the Motive of Siegfried the Fearless.

It pervades with its joyous impetuosity the ensuing scene, in which Siegfried has his sport with Mime, until tiring of it, he loosens the rope from the bear’s neck and drives the animal back into the forest. In a pretty, graceful phrase Siegfried tells how he blew his horn, hoping it would be answered by a pleasanter companion than Mime. Then he examines the sword which Mime has been forging. The Siegfried Motive resounds as he inveighs against the weapon’s weakness, then shivers it on the anvil. The orchestra, with a rush, takes up the Motive of Siegfried the Impetuous.

This is a theme full of youthful snap and dash. Mime tells Siegfried how he tenderly reared him from infancy. The music here is as simple and pretty as a folk-song, for Mime’s reminiscences of Siegfried’s infancy are set to a charming melody, as though Mime were recalling to Siegfried’s memory a cradle song of those days. But Siegfried grows impatient. If Mime really tended him so kindly out of pure affection, why should Mime to so repulsive to him; and yet why should he, in spite of Mime's repulsiveness, always return to the cave? The dwarf explains that he is to Siegfried what the father is to the fledging. This leads to a beautiful lyric episode. Siegfried says that he saw the birds mating, the deer pairing, the she-wolf nursing her cubs. Whom shall he call Mother? Who is Mime’s wife? This episode is pervaded by the lovely Motive of Love-Life.

Mime endeavours to persuade Siegfried that he is his father and mother in one. But Siegfried has noticed that the young of birds and deer and wolves look like the parents. He has seen his features reflected in the brook, and knows he does not resemble the hideous Mime. The notes of the Love-Life Motive pervade this episode. When Siegfried speaks of seeing his own likeness, we also hear the Siegfried Motive. Mime, forced by Siegfried to speak the truth, tells of Sieglinde’s death while giving birth to Siegfried. Throughout this scene we find reminiscences of the first act of "The Valkyr," the Wälsung Motive, the Motive of Sympathy, and the Love Motive. Finally, when Mime produces as evidence of the truth of his words the two pieces of Siegmund’s sword, the Sword Motive rings out brilliantly. Siegfried exclaims that Mime must weld the pieces into a trusty weapon. Then follows Siegfried’s "Wander Song," so full of joyous abandon. Once the sword welded, he will leave the hated Mime for ever. As the fish through the water, as the bird flies so free, he will flee from the repulsive dwarf. With joyous exclamations he runs from the cave into the forest.

The frank, boisterous nature of Siegfried is charmingly portrayed. His buoyant vivacity finds capital expression in the Motives of Siegfried the Fearless, Siegfried the Impetuous, and his "Wander Song," while the vein of tenderness in his character seems to run through the Love-Life Motive. His harsh treatment of Mime is not brutal; for Siegfried frankly avows his loathing for the dwarf, and we feel, knowing Mime’s plotting against the young Wälsung, that Siegfried’s hatred is the spontaneous aversion of a frank nature for an insidious one.

Mime has a gloomy soliloquy. It is interrupted by the entrance of Wotan, disguised as a wanderer. At the moment Mime is in despair because he cannot weld the pieces of Siegmund’s sword. When the wanderer departs, he has prophesied that only he who does not know what fear is -- only a fearless hero-- can weld the fragments, and that through this fearless hero Mime shall lose his life. This prophecy is reached through a somewhat curious process which must be unintelligible to any one who has not made a study of the libretto. The Wanderer, seating himself, wagers his head that he can correctly answer any three questions which Mime may put to him. Mime then asks: "What is the race born in the earth’s deep bowels?" The Wanderer answers: "The Nibelungs." Mime’ second question is: "What race dwells on the earth’s back?" The Wanderer replies: "The race of giants." Mime finally asks: "What race dwells on cloudy heights?" The Wanderer answers: "The race of the gods." The Wanderer, having thus answered correctly Mime’s three questions, now put three questions to Mime: "What is that noble race which Wotan ruthlessly dealt with, and yet which he deemeth most dear?" Mime answers correctly: "The Wälsungs." Then the Wanderer asks: "What sword must Siegfried then strike, with, dealing to Fafner death?" Mime answers correctly: "With Siegmund’s sword." "Who," asks the Wanderer, "can weld its fragments?" Mime is terrified, for he cannot answer. Then Wotan utters the prophecy of the fearless hero.

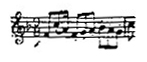

The scene is musically most eloquent. It is introduced by two motives, representing Wotan as the Wanderer. The mysterious chords of the former seem characteristic of Wotan’s disguise.

The latter, with its plodding, heavily-tramping movement, is the motive of Wotan’s wandering.

The third new motive found in this scene is characteristically expressive of the Cringing Mime.

Several motives familiar from "The Rhinegold" and "The Valkyr" are heard here. The Motive of Compact so powerfully expressive of the binding force of law, the Nibelung and Walhalla motives from "The Rhinegold," and thre Wälsungs’ Heroism motives from the first act of "The Valkyr," are among these.

When the Wanderer has vanished in the forest Mime sinks back on his stool in despair. Staring after Wotan into the sunlit forest, the shimmering rays flitting over the soft green mosses with every movement of the branches and each tremor of the leaves seem to him like flickering flames and treacherous will-o’-the-wisps. We hear the Loge Motive (Loge being the god of fire) familiar from "The Rhinegold" and the finale of "The Valkyr." At last Mime rises to his feet in terror. He seems to see Fafner in his serpent’s guise approaching to devour him, and in a paroxysm of fear he falls with a shriek behind the anvil. Just then Siegfried bursts out of the thicket, and with the fresh, buoyant "Wander Song" and the Motive of Siegfried the Fearless, the weird mystery which hung over the former scene is dispelled. Siegfried looks about him for Mime until he sees the dwarf lying behind the anvil.

Laughingly the young Wälsung asks the dwarf if he has thus been welding the sword. "The sword? The sword?" repeats Mime confusedly, as he advances, and his mind wanders back to Wotan’s prophecy of the fearless hero. Regaining his senses he tells Siegfried there is one thing he has yet to learn, namely, to be afraid; that his mother charged him (Mime) to teach fear to him (Siegfried). Mime asks Siegfried if he has never felt his heart beating when in the gloaming he heard strange sounds and saw weirdly glimmering lights in the forest. Siegfried replies that he never has. He knows not what fear is. If it is necessary before he goes forth in quest of adventure to learn what fear is he would like to be taught. But how can Mime teach him?

The Magic Fire Motive and Brünnhilde’s Slumber Motive familiar from Wotan’s farewell, and the Magic Fire scene in the third act of "The Valkyr" are heard here, the former depicting the weirdly glimmering lights with which Mime has sought to infuse dread into Siegfried’s breast, the latter prophesying that, penetrating fearlessly the fiery circle, Siegfried will reach Brünnhilde. Then Mime tells Siegfried of Fafner, thinking thus to strike terror into the young Wälsung’s breast. But far from it! Siegfried is incited by Mime’s words to meet Fafner in combat. Has Mime welded the fragments of Siegfried’s sword, asks Siegfried. The dwarf confesses his impotency. Siegfried seizes the fragment. He will forge his own sword. Here begins the great scene of the forging of the sword. Like a shout of victory the Motive of Siegfried the Fearless rings out and the orchestra fairly glows as Siegfried heaps a great mass of coal on the forge-hearth, and fanning the heat, begins to file away at the fragments of the sword.

The roar of the fire, the sudden intensity of the fierce white heat to which the young Wälsung fans the glow-these we would respectively hear and see were the music given without scenery or action, so graphic is Wagner’s score. The Sword Motive leaps like a brilliant tongue of flame over the heavy thuds of a forceful variant of the Motive of Compact, till brightly gleaming runs add to the brilliancy of the score, which reflects all the quickening, quivering effulgence of the scene. How the music flows like a fiery flood and how it hisses as Siegfried pours the molten contents of the crucible into a mould and then plunges the latter into water! The glowing steel lies on the anvil and Siegfried swings the hammer. With every stroke his joyous excitement is intensified. At last the work is done. He brandishes the sword and with one stroke splits the anvil from top to bottom. With the crash of the Sword Motive, united with the Motive of Siegfried the Fearless, the orchestra dashes into a furious prestissimo, and Siegfried shouting with glee, holds aloft the sword!

Act II. The second act opens with a darkly portentous Vorspiel. On the very threshold of it we meet Fafner in his motive, which is so clearly based on the Giant Motive that there is no necessity for quoting it. Through themes which are familiar from earlier portions of the work, the Vorspiel rises to a crashing fortissimo.

The curtain lifts on a thick forest. At the back is the entrance to Fafner’s cave, the lower part of which is hidden by rising ground in the middle of the stage, which slopes down toward the back. In the darkness the outlines of a figure are dimly discerned. It is the Nibelung Alberich, haunting the domain which hides the treasures of which he was despoiled. From the forest comes a gust of wind. A bluish light gleams from the same direction. Wotan, still in the guise of a Wanderer, enters.

The ensuing scene between Alberich and the Wanderer is from a dramatic point of view, episodical. Suffice it to say that the fine self-poise of Wotan and the maliciously restless character of Alberich are superbly contrasted. When Wotan has departed the Nibelung slips into a rocky crevice, where he remains hidden when Siegfried and Mime enter. Mime endeavours to awaken dread in Siegfried’s heart by describing Fafner’s terrible form and powers. But Siegfried’s courage is not weakened. On the contrary, with heroic impetuosity, he asks to be at once confronted with Fafner. Mime, well knowing that Fafner will soon awaken and issue from his cave to meet Siegfried in mortal combat, lingers on in the hope that both may fall, until the young Wälsung drives him away.

Now begins a beautiful lyric episode. Siegfried reclines under a linden-tree, and looks through the branches. The rustling of the trees is heard. Over the tremulous whispers of the orchestra-known from concert programs as the "Waldweben" (forest-weaving) -- rises a lovely variant of the Wälsung Motive. Siegfried is asking himself how his mother many have looked, and this variant of the theme which was first heard in "The Valkyr," when Sieglinde told Siegmund that her home was the home of woe, rises like a memory of her image. Serenely the sweet strains of the Love-Life Motive soothe his sad thoughts. Siegfried, once more entranced by forest sounds, listens intently. Bird’s voices greet him. A little feathery songster, whose notes mingle with the rustling leaves of the linden-tree, especially charms him.

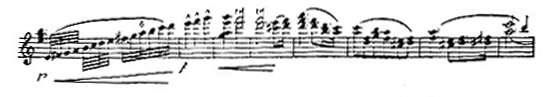

The forest voices -- the humming of insects, the piping of the birds, the amorous quiver of the branches -- quicken his half-defined aspirations. Can the little singer explain his longing? He listens, but cannot catch the meaning of the song. Perhaps, if he can imitate it he may understand it. Springing to a stream hard by, he cuts a reed with his sword and quickly fashions a pipe from it. He blows on it, but it sounds shrill. He listens again to the birds. He may not be able to imitate his song on the reed, but on his silver horn he can wind a woodland tune. Putting the horn to his lips he makes the forest ring with its notes:

The notes of the horn have awakened Fafner who now in the guise of a huge serpent or dragon, crawls toward Siegfried. Perhaps the less said about the combat between Siegfired and Fafner the better. This scene, which seems very spirited in the libretto, is ridiculous on the stage. To make it effective it should be carried out very far back-best of all out of sight -- so that the magnificent music will not be marred by the sight of an impossible monster. The music is highly dramatic. The exultant force of the Motive of Siegfried the Fearless, which rings out as Siegfried rushes upon Fafner, the crashing chord as the serpent roars when Siegfried buries the sword in its heart, the rearing, plunging music as the monster rears and plunges with agony -- these are some of the most graphic features of the score.

Siegfried raises his fingers to his lips and licks the blood from them. Immediately after the blood has touched his lips he seems to understand the bird, which has again begun its song, while the forest voices once more weave their tremulous melody. The bird tells Siegfried of the ring and helmet and of the other treasures in Fafner’s cave, and Siegfried enters it in quest of them. With his disappearance the forest-weaving suddenly changes to the harsh, scolding notes heard in the beginning of the Nibelheim scene in "The Rhinegold." Mime slinks in and timidly looks about him to make sure of Fafner’s death. At the same time Alberich issues forth from the crevice in which he was concealed. This scene, in which the two Nibelungs berate each other, is capitally treated, and its humours affords a striking contrast to the preceding scenes.

As Siegfried comes out of the cave and brings the ring and helmet from darkness to the light of day, there are heard the Ring Motive, the Motive of the Rhinedaughters’ Shout of Triumph, and the Rhinegold Motive. The forest-weaving again begins, and the birds bid the young Wälsung beware of Mime. The dwarf now approaches Siegfried with repulsive sycophancy. But under a smiling face lurks a plotting heart. Siegfried is enabled through the supernatural gifts with which he has become endowed to fathom the purpose of the dwarf, who unconsciously discloses his scheme to poison Siegfried. The young Wälsung slays Mime, who, as he dies, hears Alberich’s mocking laugh. Though the Motive of Siegfried the Fearless predominates at this point, we also hear the Nibelung Motive and the Motive of the Curse -- indicating Alberich’s evil intent toward Siegfried.

Siegfried again reclines under the linden. His soul is tremulous with an undefined longing. As he gazes in almost painful emotion up to the branches and asks if the bird can tell him where he can find a friend, his being seems stirred by awakening passion.

The music quickens with an impetuous phrase, which seems to define the first joyous thrill of passion in the youthful hero. It is the Motive of Love’s Joy:

[Music excerpt]

It is interrupted by a beautiful variant of the Motive of Love-Life, which continues until above the forest-weaving the bird again thrills him with its tale of a glorious maid who has so long slumbered upon the fire-guarded rock. With the Motive of Love’s Joy coursing through the orchestra, Siegfried bids the feathery songster continue, and, finally, to guide him to Brünnhilde. In answer, the bird flutters from the linden branch, hovers over Siegfried, and hesitatingly flies before him until it takes a definite course toward the background. Siegfried follows the little singer, the Motive of Love’s Joy, succeeded by that of Siegfried the Fearless, bringing the act to a close.

Act III. The third act opens with a stormy introduction in which the Motive of the Ride of the Valkyrs accompanies the Motive of the Gods’ Stress, the Compact, and the Erda motives. The introduction reaches its climax with the Motive of the Dusk of the Gods:

[Music excerpt]

[Music excerpt]

Then to the sombre, questioning phrase of the Motive of Fate, the action begins to disclose the significance of this Vorspiel. A wild region at the foot of a rocky mountain is seen. It is night. A fierce storm rages. In dire distress and fearful that through Siegfried and Brünnhilde the rulership of the world may pass from the gods to the human race, Wotan summons Erda from her subterranean dwelling. But Erda has no counsel for the storm-driven, conscience-stricken god.

The scene reaches its climax in Wotan’s noble renunciation of the empire of the world. Weary of strife, weary of struggling against the decree of fate, he renounces his sway. Let the era of human love supplant this dynasty, sweeping away the gods and the Nibelungs in its mighty current. It is the last defiance of all-conquering fate by the ruler of a mighty race. After a powerful struggle against irresistible forces, Wotan comprehends that the twilight of the gods will be the dawn of a more glorious epoch. A phrase of great dignity gives force of Wotan’s utterances. It is the Motive of the World’s Heritage:

[Music excerpt]

Siegfried enters, guided to the spot by the bird; Wotan checks his progress with the same spear which shivered Siegmund’s sword. Siegfried must fight his way to Brünnhilde. With a mighty blow the young Wälsung shatters the spear and Wotan disappears amid the crash of the Motive of Compact -- for the spear with which it was the chief god’s duty to enforce compacts is shattered. Meanwhile the gleam of fire has become noticeable. Fiery clouds float down from the mountain. Siegfried stands at the rim of the magic circle. Winding his horn he plunges into the seething flames. Around the Motive of Siegfried the Fearless and the Siegfried Motive flash the Magic Fire and Loge motives.

The flames, having flashed forth with dazzling brilliancy, gradually pale before the red flow of dawn till a rosy mist envelops the scene. When it rises, the rock and Brünnhilde in deep slumber under the fir-tree, as in the finale of "The Valkyr," are seen. Siegfried appears on the height in the background. As he gazes upon the scene there are heard the Fate and Slumber motives and then the orchestra weaves a lovely variant of the Freia Motive. This is followed by the softly caressing strains of the Fricka Motive. Fricka sought to make Wotan faithful to her by bonds of love, and hence the Fricka Motive in this scene does not reflect her personality, but rather the awakening of the love which is to thrill Siegfried when he has beheld Brünnhilde’s features. As he sees Brünnhilde’s charger slumbering in the grove we hear the Motive of the Valkyr’s Ride, and when his gaze is attracted by the sheen of Brünnhilde’s armour, the theme of Wotan’s farewell. Approaching the armed slumberer under the fir-tree, Siegfried raises the shield and discloses the figure of the sleeper, the face being almost hidden by the helmet.

Carefully he loosens the helmet. As he takes it off Brünnhilde’s face is disclosed and her long curls flow down over her bosom. Siegfried gazes upon her enraptured. Drawing his sword he cuts the rings of mail on both sides, gently lifts off the corselet and greaves, and Brünnhilde, in soft female drapery, lies before him. He starts back in wonder. Notes of impassioned import -- the Motive of Love’s Joy --express feelings that well up from his heart as for the first time he beholds a woman. the fearless hero is infused with fear by a slumbering woman. The Wälsung Motive, afterwards beautifully varied with the Motive of Love’s Joy, accompanies his utterances, the climax of his emotional excitement being expressed in a majestic crescendo of the Freia Motive. A sudden feeling of awe gives him at least the outward appearance of calmness. With the Motive of Fate he faces his destiny; and then, while the Freia Motive rises like a vision of loveliness, he sinks over Brünnhilde, and with closed eyes presses his lips to hers.

Brünnhilde awakens. Siegfried starts up. She rises, and with a noble gesture greets in majestic accents her return to the sight of earth. Strains of loftier eloquence than those of her greeting have never been composed. Brünnhilde rises from her magic slumbers in the majesty of womanhood:

With the Motive of Fate she asks who is the hero who has awakened her. The superb Siegfried Motive gives back the proud answer. In rapturous phrases they greet one another. It is the Motive of Love’s Greeting,

which unites their voices in impassioned accents until, as if this motive no longer sufficed to express their ecstasy, it is followed by the Motive of Love’s Passion.

which, with the Siegfried Motive, rises and falls with the heaving of Brünnhilde’s bosom.

These motives course impetuously through this scene. Here and there we have others recalling former portions of the cycle -- the Wälsung Motive, when Brünnhilde refers to Siegfried’s mother; Sieglinde; the Motive of Brünnhilde’s Pleading, when she tells him of her defiance of Wotan’s behest; a variant of the Walhalla Motive when she speaks of herself in Walhalla; and the Motive of the World’s Heritage, with which Siegfried claims her, this last leading over to a forceful climax of the Motive of Brünnhilde’s Pleading, which is followed by a lovely, tranquil episode introduced by the Motive of Love’s Peace,

succeeded by a motive, ardent yet tender-the Motive of Siegfried the Protector:

These motives accompany the action most expressively. Brünnhilde still hesitates to cast off for ever the supernatural characteristics of the Valkyr and give herself up entirely to Siegfried. The young hero’s growing ecstasy finds expression in the Motive of Love’s Joy. At last it awakens a responsive note of purely human passion in Brünnhilde and, answering the proud Siegfried Motive with the jubilant Shout of the Valkyrs and the ecstatic measures of Love’s Passion, she proclaims herself his.

With a love duet -- nothing puny and purring, but rapturous and proud -- the music-drama comes to a close. Siegfried, a scion of the Wälsung race has won Brünnhilde for his bride, and upon her finger has placed the ring fashioned of Rhinegold by Alberich in the caverns of Niebelheim, the abode of the Niebelungs. Clasping her in his arms and drawing her to his breast, he has felt her splendid physical being thrill with a passion wholly responsive to his. Will the gods be saved through them, or does the curse of Alberich still rest on the ring worn by Brünnhilde as a pledge of love?

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-25 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |