Music with Ease > 19th Century Italian Opera > La Bohème (Puccini) - Synopsis

La Bohème -

Synopsis

An Opera by Giacomo Puccini

CHARACTERS

RUDOLPH, a poet………………………………………. Tenor

MARCEL, a painter…………………………………….. Baritone

COLLINE, a philosopher……………………………….. Bass

SCHAUNARD, a musician…………………………….. Baritone

BENOIT, a landlord……………………………………. Bass

ALCINDORO, a state councilor and follower of Musetta. Bass

PARPIGNOL, an itinerant toy vendor……………………. Tenor

CUSTOM-HOUSE SERGEANT………………………… Bass

MUSETTA, a grisette……………………………………. Soprano

MIMI, a maker of embroidery…………………………… Soprano

Students, workgirls, citizens, shopkeepers, street venders, soldiers, waiters, boys, girls, etc.

Time: About 1830.

Place: Latin Quarter, Paris.

"La rappezzatrice" (the clothes mender) in Act II of the world premiere performance Puccini's opera, La bohème, at the Teatro Regio di Torino, Turin, Italy, on 1 February 1893. The costume of the clothes mender was designed by: Adolf Hohenstein (1854-1928).

"La Bohème" is considered by many Puccini’s finest score. There is little to choose, however, between it, "Tosca," and "Madama Butterfly." Each deals successfully with its subject. It chances that, as "La Bohème" is laid in the Quartier Latin, the students’ quartet of Paris, where gayety and pathos touch elbows, it laughs as well as weeps. Authors and composers who can tear passion to tatters are more numerous than those who have the light touch of high comedy. The latter, a distinguished gift, confers distinction upon many passages in the score of "La Boheme," which anon sparkles with merriment, anon is eloquent of love, anon is stressed by despair.

Act I. The garret in the Latin Quartet, where live the inseparable quartet -- Rudolph, poet; Marcel, painter; Colline, philosopher; Schaunuard, musician, who defy hunger with cheerfulness and play pranks upon the landlord of their meager lodging, when he importunes them for his rent.

When the act opens, Rudolph is at a table writing, and Marcel is at work on a painting, "The Passage of the Red Sea." He remarks that, owing to lack of fuel for the garret stove, the Red Sea is rather cold.

"Questo mar rosso" (This Red Sea), runs the duet, in the course of which Rudolph says that he will sacrifice the manuscript of his tragedy to the needs of the stove. They tear up the first act, throw it into the stove, and light it. Colline comes in with a bundle of books he has vainly been attempting to pawn. Another act of the tragedy goes into the fire, by which they warm themselves, still hungry.

But relief is nigh. Two boys enter. They bring provisions and fuel. After them comes Schaunard. He tosses money on the table. The boys leave. In vain Schaunard tries to tell his friends the ludicrous details of his three days’ musical engagement to an eccentric Englishman. It is enough for them that it has yielded fuel and food, and that some money is left over for the immediate future. Between their noise in stoking the stove and unpacking the provisions, Schaunard cannot make himself heard.

Rudolph locks the door. Then all go to the table and pour out wine. It is Christmas eve. Schaunard suggests that, when they have emptied their glasses, they repair to their favourite resort, the Café Momus, and dine. Agreed. Just then there is a knock. It is Benoit, their landlord, for the rent. They let him in and invite him to drink with them. The sight of the money on the table reassures him. He joins them. The wine loosens his tongue. He boasts of his conquests of women at shady resorts. The four friends feign indignation. What! He, a married man, engaged in such disreputable proceedings! They seize him, lift him to his feet, and eject him, locking the door after him.

The money on the table was earned by Schaunard, but, according to their custom, they divide it. Now, off for the Café Momus -- that is, all but Rudolph, who will join them soon -- when he has finished an article he has to write for a new journal, the Beaver. He stands on the landing with a lighted candle to aid the others in making their way down the rickety stairs.

With little that can be designated as set melody, there nevertheless has not been a dull moment in the music of these scenes. It has been brisk, merry and sparkling, in keeping with the careless gayety of the four dwellers in the garret.

Re-entering the room, and closing the door after him, Rudolph clears a space on the table for pens and paper, then sits down to write. Ideas are slow in coming. Moreover, at that moment, there is a timid knock at the door.

"Who’s there?" he calls.

It is a woman’s voice that says, hesitatingly. "Excuse me, my candle has gone out."

Rudolph runs to the door, and opens it. On the threshold stands a frail, appealingly attractive young woman. She has in one hand an extinguished candle, in the other a key. Rudolph bids her come in. She crosses the threshold A woman of haunting sweetness in aspect and manner has entered Bohemia.

She lights her candle by his, but, as she is about to leave, the draught again extinguishes it. Rudolph’s candle also is blown out, as he hastens to relight hers. The room is dark, save for the moonlight that, over the snow-clad roofs of Paris, steals in through the garret window. Mimi exclaims that she has dropped the key to the door of her room. They search for it. He finds it but slips it into his pocket. Guided by Mimi’s voice and movements, he approaches. As she stoops, his hand meets hers. He clasps it.

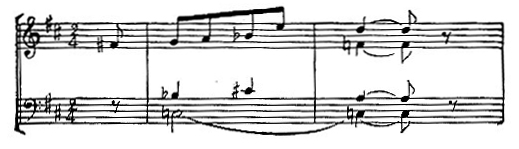

"Che gelida manina" (How cold your hand), he exclaims with tender solicitude. "Let me warm it into life." He then tells her who he is, in what has become known as the "Racconto di Rodolfo" (Rudolph’s Narrative), which, from the gentle and solicitous phrase. "Che gelida manina," followed by the proud exclamation, "Sono un poeta" (I am a poet), leads up to an eloquent avowal of his dreams and fancies. Then comes the girl’s charming "Mi chiamano Mimi" (They call me Mimi), in which she tells of her work and how the flowers she embroiders for a living transport her from her narrow room out into the broad fields and neadows. "Mi chiamano Mimi" is as follows: -

Her frailty, which one can see is caused by consumption in its early stages, makes her beauty the more appealing to Rudolph.

His friends call him from the street below. Their voices draw Mimi to the window. In the moonlight she appears even lovelier to Rudolph. "O soave fanciulla" (Thou beauteous maiden), he exclaims, as he takes her to his arms. This is the beginning of the love duet, which, though it be sung in a garret, is as impassioned as any that, in opera, has echoed through the corridors of palaces, or the moonlit colonnades of forests by historic rivers. The theme is quoted here in the key, in which it occurs, like a premonition, a little earlier in the act.

The theme of the love duet is used by the composer several times in the course of the opera, and always in association with Mimi. Especially in the last act does it recur with poignant effect.

Act II. A meeting of streets, where they form a square, with shops of all sorts, and the Café Momus. The square is filled with a happy Christmas eve crowd. Somewhat aloof from this are Rudolph and Mimi. Colline stands near the shop of a clothes dealer. Schaunard is haggling with a tinsmith over the price of a horn. Marcel is chaffing the girls who jostle against him in the crowd.

There are street vendors crying their wares; citizens, students, and work girls, passing to and fro and calling to each other; people at the café giving orders -- a merry whirl, depicted in the music by snatches of chorus, bits of recitative, and an instrumental accompaniment that runs through the scene like a many-coloured thread, and holds the pattern together.

Rudolph and Mimi enter a bonnet shop. The animation outside continues. When the two lovers come out of the shop, Mimi is wearing a new bonnet trimmed with roses. She looks about.

"What is it?" Rudolph asks suspiciously.

"Are you jealous?" asks Mimi.

"The man in love is always jealous."

Rudolph’s friends are at a table outside the café. Rudolph joins them with Mimi. He introduces her to them as one who will make their party complete, for he "will play the poet, while she’s the muse incarnate."

Parpignol, the toy vendor, crosses the square and goes off, followed by children, whose mothers try to restrain them. The toy vender is heard crying his wares in the distance. The quartet of Bohemians, now a quintet through the accession of Mimi, order eatables and wine.

Shopwomen, who are going away, look down one of the streets, and exclaim over someone whom they see approaching.

"’Tis Musetta! My, she is gorgeous! -- Some stammering old dotard is with her."

Musetta and Marcel have loved, quarreled, and parted. She has recently put up with the aged but wealthy Alcindoro de Mittoneaux, who, when she comes upon the square, is out of breath trying to keep up with her.

Despite Musetta’s and Marcel’s attempt to appear indifferent to each other’s presence, it is plain that they are not so. Musetta has a chic waltz song, "Quando me ‘n vo soletta per la via" (As through the streets I wander onward merrily), one of the best known numbers of the score, which she deliberately sings at Marcel, to make him aware, without arousing her aged gallant’s suspicions, that she still loves him.

Feigning that a shoe hurts her, she makes the ridiculous Alcindoro unlatch and remove it, and trot off with it to the cobbler’s. She and Marcel then embrace, and she joins the five friends at their table, and the expensive supper ordered by Alcindoro is served to them with their own.

The military tattoo is heard approaching from the distance. There is great confusion in the square. A waiter brings the bill for the Bohemians’ order. Schaunard looks in vain for his purse. Musetta comes to the rescue. "Make one bill of the two orders. The gentleman who was with me will pay it."

The patrol enters, headed by a drum major. Musetta, being without her shoe, cannot walk, so Marcel and Colline lift her between them to their shoulders, and carry her through the crowd, which, sensing the humour of the situation, gives her an ovation, then swirls around Alcindoro, whose foolish, senile figure, appearing from the direction of the cobbler’s shop with a pair of shoes for Musetta, it greets with jeers. For his gay ladybird has fled with her friends from the Quartier, and left him to pay all the bills.

Act III. A gate to the city of Paris on the Orleans road. A toll house at the gate. To the left a tavern, from which, as a signboard hangs Marcel’s picture of the Red Sea. Several plane trees. It is February. Snow is on the ground. The hour is that of dawn. Scavengers, milk women, truckmen, peasants with produce, are waiting to be admitted to the city. Custom-house officers are seated, asleep, around a brazier. Sounds of revelry are heard from the tavern. These, together with characteristic phrases, when the gate is opened and people enter, enliven the first scene.

Into the small square comes Mimi from the Rue d’Enfer, which leads from the Latin Quarter. She looks pale, distressed, and frailer than ever. A cough racks her. Now and then she leans against one of the bare, gaunt plane trees for support.

A message from her brings Marcel out of the tavern. He tells her he finds it more lucrative to paint signboards than pictures. Musetta gives music lessons. Rudolph is with them. Will not Mimi join them? She weeps, and tells him that Rudolph is so jealous of her she fears they must part. When Rudolph, having missed Marcel, comes out to look for him, Mimi hides behind a plane tree, from where she hears her lover tell his friend that he wishes to give her up because of their frequent quarrels. "Mimi è una civetta" (Mimi is a heartless creature) is the burden of his song. Her violent coughing reveals her presence. They decide to part -- not angrily, but regretfully: "Addio, senza rancore" (Farewell, then, I wish you well), sings Mimi.

Meanwhile Marcel, who has re-entered the tavern, has caught Musetta flirting with a stranger. This starts a quarrel, which brings them out into the street. Thus the music becomes a quartet: "Addio, dolce svegliare" (Farewell, sweet love), sing Rudolph and Mimi, while Marcel and Musetta upbraid each other. The temperamental difference between the two women, Mimi gentle and melancholy, Musetta aggressive and disputatious, and the difference in the effect upon the two men, are admirably brought out by the composer. "Viper!" "Toad!" Marcel and Musetta call out to each other, as they separate; while the frail Mimi sighs, "Ah! that our winter night might last forever," and she and Rudolph sing, "Our time for parting’s when the roses blow."

Act IV. The scene is again the attic of the four Behomians. Rudolph is longing for Mimi, of whom he has heard nothing, Marcel for Musetta, who, having left him, is indulging in one of her gay intermezzos with one of her wealthy patrons. "Ah, Mimi, tu piu" (Ah, Mimi, fickle-hearted), sings Rudoplh, as he gazes at the little pink bonnet he bought her at the milliner’s shop Christmas eve. Schaunard thrusts the water bottle into Colline’s hat as if the latter were a champagne cooler. The four friends seek to forget sorrow and poverty in assuming mock dignities and then indulging in a frolic about the attic. When the fun is at its height, the door opens and Musetta enters. She announces that Mimi is dying and, as a last request, has asked to be brought back to the attic, where she had been so happy with Rudolph. He rushes out to get her, and supports her feeble and faltering footsteps to the cot, on which he gently lowers her.

She coughs; her hands are very cold. Rudolph takes them in his to warm them. Musetta hands her earrings to Marcel, and bids him go out and sell them quickly, then buy a tonic for the dying girl. There is no coffee, no wine. Colline takes off his overcoat, and, having apostrophized it in the "Song of the Coat," goes out to sell it, so as to be able to replenish the larder. Musetta runs off to get her muff for Mimi, her hands are still so cold.

Rudolph and the dying girl are now alone. This tragic moment, when their love revives too late, finds expression, at once passionate and exquisite, in the music. The phrases "How cold your hand," "They call me Mimi," from the love scene in the first act, recur like mournful memories.

Mimi whispers of incidents from early in their love. "Te lo rammenti" (Ah! do you remember).

Musetta and the others return. There are tender touches in the good offices they would render the dying girl. They are aware before Rudolph that she is beyond aid. In their faces he reads what has happened. With a cry, "Mimi! Mimi!" he falls sobbing upon her lifeless form. Musetta kneels weeping at the foot of the bed. Schaunard, overcome sinks back into a chair. Colline stands dazed at the suddenness of the catastrophe. Marcel turns away to hide his emotion.

Mi chiamano Mimi!

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-25 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |