Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > Music of The Flying Dutchman (Wagner)

The Music of 'The Flying Dutchman'

(German title: Der fliegende Holländer)

An Opera by Richard Wagner

In listening to "The Flying Dutchman," we do not need to trouble ourselves much about Wagner’s essential art theories as these were developed later in "Tannhäuser" and its successors. It is true that, unlike its predecessor, "Rienzi" -- an opera in the old sense of the term -- "The Flying Dutchman" was definitely a music-drama. Wagner had already revolted against the conventional stage characters who advanced to the footlights and poured out roulades at the audience. He must now have his characters "move, act, and sing in a way that suited the situation, according to the laws of ordinary common-sense." He describes his method in connection especially with the "Dutchman." Thus:

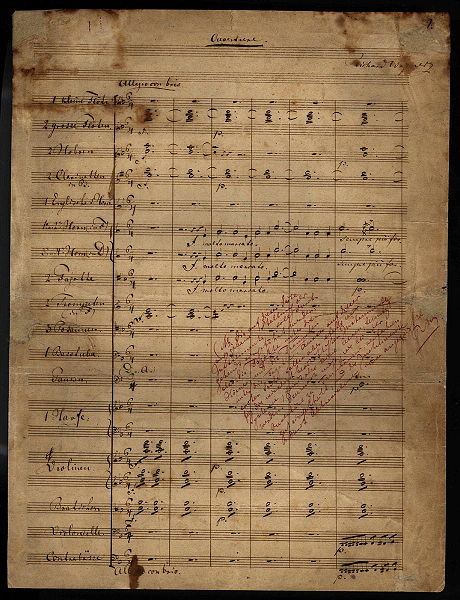

Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman) Overture by Richard Wagner. This is a manuscript copy (circa 1843) in Wagner's own handwriting and contains notes to his publisher.

The modern division into arias, duets, finales, and so on, I had at once to give up, and in their stead narrate the Saga in one breath, just as should be done in a good poem. In this wise I brought forth an opera, of which, now that it has been performed, I cannot conceive how it could have pleased. For in its every external feature it is so completely unlike that which one now calls opera, that I see indeed how much I demanded of the public, namely, that they should with one blow dissever themselves from all that which had hitherto entertained and appealed to them in the theatre.

It was not quite such a severance as that, as Wagner himself in another place, admitted. He admitted that (as regards the poetical form at least) his "Dutchman" was by no means " a fixed and finished entity." On the contrary, he asked his friends to take it as showing himself in the process of "becoming." He added, however, that the form of the "Dutchman," as of all his later poems, down to even the minutiae of their musical setting, was "dictated to me by the subject matter alone, insomuch as that had become absorbed into a definite colouring of my life, and in so far as I had gained by practice and experience on my own adopted path any general aptitude for artistic construction."

For all this, Wagner did not, in "The Flying Dutchman," entirely abandon the traditional forms of the Italian singing-opera. For here are solos, duets, choruses, &c., just as in other operas of the time. Not yet, moreover, was he entirely possessed by the leitmotiv or guiding-theme system which later became the characteristic feature of his works, though the germ of the system is certainly embedded in the score.

In "The Flying Dutchman" Wagner is only feeling his way towards this essential principle of his art. Hence the work (its unity somewhat impaired on that account) is half old style, half new, with, on the whole, the balance in favour of the old. Spohr summed it up very well when he wrote, apropos of that early performance under his direction at Cassel:

This work, though it comes near the boundary of the new romantic school à la Berlioz, and is giving me unheard-of trouble with its immense difficulties, yet interests me in the highest degree since it is obviously the product of pure inspiration, and does not, like so much of our modern operatic music, betray in every bar the striving to make a sensation or to please. There is much creative imagination in it; its invention is thoroughly noble, and it is well written for the voices, while the orchestral part, though enormously difficult, and somewhat overladen, is rich in new effects and will certainly, in our large theatre, be perfectly clear and intelligible.

Even better, perhaps, is Mr. Henderson’s estimate in his introduction to the Schirmer vocal score of the drama. He says:

Wagner divined clearly the necessity of subordinating mere pictorial movement to the play of emotion, and it will easily be discerned that the three acts of "The Flying Dutchman" reduce themselves to a few broad emotional episodes. In the first our attention is centred upon the longing of the Dutchman, and in the second upon the love of Senta. In the third we have the inevitable and hopeless struggle of the passion of Erik against Senta’s love. All music not designed to embody these broad emotional states is scenic, such as the storm music and choruses of the sailors and the women.

Coming to details of the music, we have first of all to consider the Overture, a piece so familiar in the concert-room that it may be worth while summarizing Wagner’s own description of it, long as even a summary must be. The summary repeats, to a great extent, the outline already given of the several Acts, but that will only further impress the story upon the mind of the listener. Here, then, is Wagner’s explanation of the poetical purport of this very fine piece of orchestral writing:

Driven along by the fury of the gale, the terrible ship of the "Flying Dutchman" approaches the shore, and reaches the land, where its captain has been promised he shall one day find salvation and deliverance; we hear the compassionate tones of this saving promise, which affect us like prayers and lamentations. Gloomy in appearance and bereft of hope, the doomed man is listening to them also; weary, and longing for death, he paces the strand; while his crew, worn out and tired of life, are silently employed in "making all taut" on board. How often has he, ill-fated, already gone through the same scene! How often has he steered his ship o’er ocean’s billows to the inhabited shores, on which, at each seven years’ truce, he has been permitted to land! How many times has he fancied that he has reached the limit of his torments, and, alas! how repeatedly has he, terribly undeceived, been obliged to betake himself again to his wild wanderings at sea! In order that he may secure release by death, he has made common cause in his anguish with the floods and tempests against himself; his ship he has driven into the gaping gulf of the billows, yet the gulf has not swallowed it up; through the surf of the breakers he has steered it upon the rocks, yet the rocks have not broken it in pieces. All the terrible dangers of the sea, at which he once laughed in his wild eagerness for energetic action, now mock at him. They do him no injury; under a curse he is doomed to wander o’er ocean’s wastes, for ever in quest of treasures which fail to re-animate him, and without finding that which alone can redeem him! Swiftly a smart-looking ship sails by him; he hears the jovial familiar song of its crew, as, returning from a voyage, they make jolly on their nearing home. Enraged at their merry humour, he gives chase, and coming up with them in the gale, so scares and terrifies them, that they become mute in their fright, and take to flight. From the depth of his terrible misery he shrieks out for redemption; in his horrible banishment from mankind it is a woman that alone can bring him salvation. Where and in what country tarries his deliverer? Where is there a feeling heart to sympathetise with his woes? Where is she who will not turn away from him in horror and fright, like those cowardly fellows who in their terror hold up the cross at his approach! A lurid light now breaks through the darkness; like lighting it pierces his tortured soul. It vanishes, and again beams forth; keeping his eye upon this guiding star, the sailor steers towards it, o’er waves and floods. What is it that so powerfully attracts him, but the gaze of a woman, which, full of sublime sadness and divine sympathy, is drawn towards him! A heart has opened its lowest depths to the awful sorrows of this ill-fated one; it cannot but sacrifice itself for his sake, and breaking in sympathy for him, annihilate itself in his woes. The unhappy one is overwhelmed at this divine appearance; his ship is broken in pieces and swallowed up in the gulf of the billows; but he, saved and exalted, emerges from the waves, with his victorious deliverer at his side, and ascends to heaven, led by the rescuing hand of sublimest love.

Thus is this fresh and picturesque composition, this magic and tempestuous "foreword" to a great drama outlined by its composer.

The Overture thus disposed of, one can only note briefly the general musical characteristics of the opera itself. Commonplaces and conventionalities there are in it; but the score contains many passages of persuasive beauty and many points of vital dramatic force. Wagner was always happily inspired by the sea, and the music of the First Act could not be more picturesquely and originally weird. Indeed it may be said that the atmosphere of the Northern Sea breathes throughout, from the Overture to the Sailors’ Chorus in the last Act. This has often been remarked as especially notable in a man born and living for the greater part of his days hundreds of miles away from the sea. No one can fail to be struck with the ghostly music which accompanies the various entries of the demon ship. "The shrilling of the north wind, the roaring of the waves, the breaking of cordage, the banging of booms, an uncanny sound in a dismal night at sea" -- these are all suggested with the most vivid realism. The pilot’s song is excellent, and the stormy. "Ho! e Ho!" chorus is in a popular, rhythmical, melodic style.

The Spinning Song, one of the most popular numbers, is a purely lyric composition, a real "home-melody." Its drowsy hum is exactly what is required to put the listener in the mood for sympathising with Senta and her dreams. The Sailors’ Choruses are all bright and tuneful. Senta’s ballad in the second act is written in a plain-song form, yet is intensely dramatic in its expression. I have indicated that in "The Flying Dutchman" only the germ of the leitmotiv system is to be found. There are, in fact, only two principal guiding themes in the whole drama, and both are heard in this ballad. The first is a somber phrase expressive of the eternal unrest of the Dutchman --

The second is a tender melody intended to portray the "salvation principle" which animates the self-sacrificing Senta --

Here, again, Wagner himself may be quoted with illuminative interest. Speaking of Senta’s ballad, he says:

In this piece I unconsciously laid the thematic germ of the whole music of the opera: it was the picture in petto of the whole drama such as it stood before soul; and when I was about to betitle the finished work, I felt strongly tempted to call it a "dramatic ballad." In the eventual composition of the music the thematic picture, thus evoked, spread itself quite instinctively over the whole drama as one continuous tissue. I had only without further initiative to take the various thematic germs included in the ballad and develop them to their legitimate conclusions, and I had all the chief moods of this poem, quite of themselves, in definite shapes before me. I should have had stubbornly to follow the example of the self-willed opera-composer had I chosen to invent a fresh motive for each recurrence of one and the same mood in different senses; a course whereto I naturally did not feel the smallest inclination, since I had only in mind the most intelligible portrayal of the subject-matter and not a mere conglomerate of operatic numbers.

The Third Act is, musically, perhaps the least satisfactory as a whole. Here "the paucity of the material forced Wagner to spin his web very thin indeed." The contrasted choruses of joyous wedding guests and phantom wanderers on the waves are, no doubt, somewhat theatrical, though one generous critic has declared that they bear the hall-mark of genius. At any rate, the Act ends effectively; and the intelligent listener comes away feeling that it was worth while hearing "The Flying Dutchman" at once for its intrinsic merits and as a medium for a study of the embryonic Wagner. It shows the development of his musical style -- marks the transition period in his career.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-25 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |