Music with Ease > 19th Century Italian Opera > Cavalleria Rusticana - Music (Mascagni)

The Music of 'Cavalleria Rusticana'

An Opera by Pietro Mascagni

"Cavalleria Rusticana" (Rustic Chivalry) has had much adverse criticism as well as generous appreciation; as to its success there can be only one opinion. Since its first performance in 1890 it has been given all over the world, and has never failed anywhere. Still a favourite with the music-loving public, it is likely for many a day to come to retain its position in the operatic repertoire.

There are several qualities necessary for the writing of grand opera, but the two most essential are the gift of melody and the dramatic sense. Both of these Mascagni has in abundance. In "Cavalleria" the melody is not always original, it is occasionally reminiscent of other composers; but there is quite enough true inspiration to show that the composer need borrow from no one, while dramatic force and power of declamation are prominent features of the work.

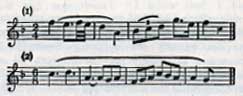

The orchestral prelude at once sounds the note of tragedy, preparing the listener for the stormy drama to follow. It begins with a solemn melody, used later as accompaniment when Santuzza begs Lucia to pray for her. Then two striking themes from the deut between Santuzza and Turiddu are introduced, which may be called the motives of entreaty:

At that part of the first theme where, in the duet, Santuzza beseeches him most passionately to take her back to his heart, the orchestra is suddenly silent and the charming and characteristic Siciliana is sung behind the curtain to a harp accompaniment. This is Turiddu’s answer to Santuzza’s pleading. It dies away pianissimo, and once more the orchestra blazes forth in continuation of the phrase interrupted by the love song. After a connecting figure, the second theme from the duet is given out; and finally the repetition of the first brings the introduction to a close.

The opening chorus, with its piquant waltz rhythm and fresh, spring-like melody, is brimful of life and sunlight, suggesting the resurrection of nature and the consequent joy and gratitude of man. In marked contrast to this number is the largo passage for the orchestra, which foreshadows, Santuzza’s entrance. Its first phrase must be specially noted -- the motive of her despair -- for we shall hear it again and again:

![]()

Now Santuzza appears, and Mascagni’s gift of declamation is at once apparent in her opening phrases, in which she is musically characterised. At the end of the scena the despair motive is again introduced in the orchestra, when she declares herself accursed. Alfio’s song which follows is bright and lively, in keeping with the joyous, happy-go-lucky nature of the carrier.

The prayer, though not markedly original and not particularly "churchy" in feeling, is a telling piece of writing, and its stage effect is impressive, though somewhat artificial. At its conclusion the tragic element once more reasserts itself in the very fine Romance in which Santuzza tells Lucia the sad story of unfaithful love. It is direct and simple in style and full of character. The insistent theme in the bass is typical of her jealousy and of Lola’s treachery:

![]()

It is heard several times in the orchestra during the recital, and again later in the work. The phrase in E major is descriptive of Santuzza’s absorbing love for Turiddu:

![]()

At the end of the narrative the music assumes a gentle, tender character, when the distracted girl begs Lucia to pray for her; while at the same time the opening theme of the prelude is heard in the orchestra.

The duet for Santuzza and Turiddu contains, besides the two motives given out in the prelude, another arresting melody sung first by Turiddu and then taken up by Santa. Towards the close of the duet Santa’s love-theme is heard pianissimo in the orchestra accompanying her entreaties. The light, dainty Stornello ( a sort of improvised Italian folk-song), in waltz rhythm, sung by Lola behind the scenes, enhances the grim despair of this number, throughout which the composer shows a wonderful power of musical characterization. Lola, the heartless flirt; Santa, the deserted; and Turiddu, the fickle -- all are described in the music allotted to them. From the dramatic point of view it is a strong scene of passionate realism, and the music has certainly played its part in heightening the emotional effect.

As Turiddu rushes into the church and Santa curses him, the despair motive is heard in the orchestra fortissimo; then gradually the tension relaxes, the music softens to pianissimo, and a few bars reminiscent of Alfio’s song of the road herald the entrance of the carrier. When Santa tells Alfio that his wife is false, the theme in the bass typical of her jealousy and of Lola’s treachery rises from the orchestra again and again. A short, marked phrase associated with Alfio’s revenge, and a plaintive wailing theme suggestive of his despair are also heard repeatedly. At the close of the number a striking effect is produced by a whirling chromatic passage in unison, apparently indicating the impending catastrophe.

The conception of the Intermezzo was a happy thought. Mascagni wished to show that, while the quartet of Sicilian peasants were living at white heat, so to speak, the great world outside was rolling on just as usual, quietly and serenely, all unconscious of this struggle to the death of human passions. He intended to create the feeling of largeness and peaceful repose, which should come as a relief after a scene of concentrated love, hatred, and revenge. And he has succeeded.

The opening, a phrase from the prayer, is adequately conceived, but unfortunately in the second part the means Mascagni has thought fit to use scarcely recommend themselves to a musician. The melody is cheap, and so is the combination of instruments. Probably no one could have made much more out of a passage for the violins in unison, with a harp and organ accompaniment. This movement is not on the same level as the rest of the opera, and it is indeed curious that the weakest part should have become the most popular number. In spite, however, of its barrel-organ fame, and in spite of what musicians may think of its banal character, the Intermezzo still has the effect desired by the composer. Thus has he fulfilled his intention.

In the beginning of the second part the music which accompanied the peasants on their way to church is once more heard, and as they turn their steps homeward they are again singing of Easter. The "Brindisi," or drinking song, with its stirring chorus, has the requisite verve, and though somewhat reminiscent of other songs of the same class, serves its purpose well. Then with the entrance of Alfio and on to the end the audience is once more at high tension.

Turiddu’s farewell to his mother is full of tenderness. Particularly beautiful is the broad phrase in which he commends Santa to her care, and entreats her to pray for him. When he has gone, an agitated figure in the bass, beginning piano and increasing to fortissimo, seems to indicate the terror-stricken condition of his wretched mother. With the entrance of Santuzza, her love motive is thundered forth from the orchestra, merging into a phrase from the prayer, and culminating in a crash ffff. A roll of the drums is then heard ppp, with a weird chord for the brass – "Turiddu is killed!" When both women faint away, the theme of despair rises solemnly for the last time, and as the curtain falls tranquilly the tragedy ends with a rushing chromatic passage in unison.

In his treatment of the orchestra Mascagni does not show any special originality, but he has a fine idea of light and shade, though his contrasts are now and again too violent. Sometimes he is noisy -- more so than the occasion would seem to demand -- at other times lacking in fulness; but on the whole his scoring is musicianly, highly coloured, and dramatically effective.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-25 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |