Music with Ease > 19th Century Italian Opera > The Barber of Seville (Rossini) - Synopsis

The Barber of Seville - Synopsis

(Italian title: Il barbiere di Siviglia)

An Opera by Gioacchino Antonio Rossini

CHARACTERS

COUNT ALMAVIVA……………………………….. Tenor

DOCTOR BARTOLO……………………………….. Bass

BASILIO, a Singing Teacher……………………….. Bass

FIGARO, a Barber…………………………………… Baritone

FIORELLO, servant to the Count…………………… Bass

AMBROSIO, servant to the Doctor…………………. Bass

ROSINA, the Doctor’s ward………………………… Soprano

BERTA (or MARCELLINA), Rosina’s Governess…. Soprano

Notary, Constable, Musicians and Soldiers.

Time: Seventeenth Century.

Place: Seville, Spain.

Upon episodes in Beaumarvchais’s trilogy of "Figaro" comedies two composers, Mozart and Rossini, based operas that have long maintained their hold upon the repertoire. The three Neaumarchais comedies are "Le Barbiere de Sevilla," "Le Marriage de Figaro," and "La Mère Coupable." Mozart selected the second of these, Rossini the first; so that although in point of composition Mozart’s "Figaro" (May, 1786) antedates Rossini’s "Barbiere" (February, 1816) by nearly thirty years. "Il Barbiere di Siviglia" precedes "Le Nozze di Figaro" in point of action. In both operas Figaro is a prominent characters, and, while the composers were of wholly different nationality and race, their music is genuinely and equally sparkling and witty. To attempt to decide between them by the flip of a coin would be "heads I win, tails you lose."

There is much to say about the first performance of "Il Barbiere di Siviglia"; also about the overture, the origin of Almaviva’s graceful solo, "Ecco redente il cielo," and the music selected by prima donnas to sing in the "lesson scene" in the second act. But these details are better preceded by some information regarding the story and the music.

Figaro, the general factotum [servant who manages his master's affairs], busybody and barber in Rossini's opera, The Barber of Seville

Act I, Scene I. A street by Dr. Bartolo’s house. Count Almaviva, a Grandee of Spain, is desperately in love with Rosina, the ward of Doctor Bartolo. Accompanied by his servant Fiorello and a band of lutists, he serenades her with the smooth, flowing measures of "Ecco ridente il cielo," (Lo, smiling in the Eastern sky).

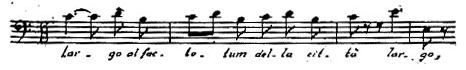

Just then Figaro, the barber, the general factotum and busybody of the town, dances in, singing the famous patter air, "Largo al factotum della città" (Room for the city’s factotum).

He is Dr. Bartolo’s barber, and, learning from the Count of his heart’s desire, immediately plots with him to bring about his introduction to Rosina. There are two clever duets between Figaro and the Count -- one in which Almaviva promises money to the Barber; the other in praise to love and pleasure.

Rosina is strictly watched by her guardiam, Doctor Bartolo, who himself plans to marry his ward, since she has both beauty and money. In this he is assisted by Basilio, a music-master. Rosina, however, returns the affection of the Count, and, in spite of the watchfulness of her guardian, she contrives to drop a letter from the balcony to Almaviva, who is still with Figaro below, declaring her passion, and at the same time requesting to know her lover’s name.

Scene 2. Room in Dr. Bartolo’s house. Rosina enters. She sings the brilliant "Una voce poco fa" (A little voice I heard just now),

followed by "Io sono decile" (With mild and docile air).

Figaro, who has left Almaviva and come in from the street, tells her that the Count is Signor Lindor, claims him as cousin, and adds that the young man is deeply in love with her. Rosina is delighted. She gives him a note to convey to the supposed Signor Lindor. (Duet, Rosina and Figaro: "Dunque io son, tu non m’ingani?" – Am I his love, or dost thou mock me?)

Meanwhile Bartolo has made known to Basilio his suspicions that Count Almaviva is in love with Rosina. Basilio advises to start a scandal about the Count and, in an aria ("La calumnia") remarkable for its descriptive crescendo, depicts how calumny may spread from the first breath to a tempest of scandal.

To obtain an interview with Rosina, the Count disguises himself as a drunken soldier, and forces his way into Bartolo’s house. The disguise of Almaviva is penetrated by the guardian, and the pretended solider is placed under arrest, but is at once released upon secretly showing the officer his order as a Grandee of Spain. Chorus, preceded by the trio, for Rosina, Almaviva and Bartoloa -- "Fredda ed immobile" (Awestruck and immovable).

Act II. The Count again enters Bartolo’s house. He is now disguised as a music-teacher, and pretends that he has been sent by Basilio to give a lesson in music, on account of the illness of the latter. He obtains the confidence of Bartolo by producing Rosina’s letter to himself, and offering to persuade Rosina that the letter has been given him by a mistress of the Count. In this manner he obtains the desired opportunity, under the guise of a music lesson -- the "music lesson" scene, which is discussed below -- to hold a whispered conversation with Rosina. Figaro also manages to obtain the keys of the balcony, an escape is determined on at midnight, and a private marriage arranged. Now, however, Basilio makes his appearance. The lovers are disconcerted, but manage, by persuading the music master that he really is ill -- an illness accelerated by a full purse slipped into his hand by Almaviva -- to get rid of him. Duet for Rosina and Almaviva, "Buona sera, mio Signore" (Fare you well then, good Signore).

When the Count and Figaro have gone, Bartolo, who possesses the letter Rosina wrote to Almaviva, succeeds, by producing it, and telling her he secured it from another lady-love of the Count, in exciting the jealousy of his ward. In her anger she disclosed the plan of escape and agrees to marry her guardian. At the appointed time, however, Figaro and the Count make their appearance-the lovers are reconciled, and a notary, procured by Bartolo for his own marriage to Rosina, celebrates the marriage of the loving pair. When the guardian enters, with officers of justice, into whose hands he is about to consign Figaro and the Count, he is too late, but is reconciled by a promise that he shall receive the equivalent of his ward’s dower.

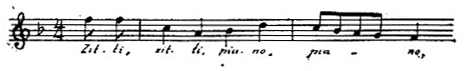

Besides the music that has been mentioned, there should be reference to "the big quintet" of the arrival and departure of Basilio. Just before Almaviva and Figaro enter for the elopement there is a storm. The delicate trio for Almaviva, Rosina and Figaro, "Zitti, zitti, piano" (Softly, softly and in silence), bears probably without intention, a resemblance to a passage in Haydn’s "Seasons."

The first performance of "Il Barbiere di Siviglia," an opera that has held its own for over a century, was a scandalous failure, which, however, was not without its amusing incidents. Castil-Blaze, Giuseppe carpani in his "Rossiniane," and Stendhal in "Vie de Rossini" (a lot of it "cribbed" from Carpani) have told the story. Moreover the Rosina of the evening, Mme. Giorgi-Righetti, who was both pretty and popular, has communicated her reminiscences.

December 26, 1815, Duke Cesarini, manager of the Argentine Theatre, Rome, for whom Rossini had contracted to write two operas, brought out the first of these, "Torvaldo e Dorliska," which was poorly received. Thereupon Cesarini handed to the composer the libretto of "Il Barbiere di Siviglia," which Paisiello, who was still living, had set to music more than half a century before. A pleasant memory of the old master’s work still lingered with the Roman public. The honorarium was 400 Roman crowns (about $400) and Rossini also was called upon to preside over the orchestra at the pianoforte at the first three performances. It is said that Rossini composed his score in a fortnight. Even if not strictly true, from December 26th to the February 5th following is but little more than a month. The young composer had too much sense not to honour Paisiello; or, at least, to appear to. He hastened to write to the old composer. The latter, although reported to have been intensely jealous of the young maestro (Rossini was only twenty-five) since the sensational success of the latter’s "Elisabetta, Regina d’Inghilterra" (Elizabeth, Queen of England), Naples, 1815, replied that he had no objection to another musician dealing with the subject of his opera. In reality, it is said, he counted on Rossini’s making a glaring failure of the attempt. The libretto was rearranged by Sterbini, and Rossini wrote a preface, modest in tone, yet not without a hint that he considered the older score out of date. But he took the precaution to show Paisiello’s letter to all the music lovers of Rome, and insisted on changing the title of the opera to "Almaviva, ossia l'Inutile Precauzione" (Almaviva, or the Useless Precautions).

Nevertheless, as soon as the rumour spread that Rossini was making over Paisiello’s work, the young composer’s enemies hastened to talk in the cafés about what they called his "underhand action." Paisiello himself, it is believed, was not foreign to these intrigues. A letter in his handwriting was shown to Rossini. In this he is said to have written from Naples to one of his friends in Rome urging him to neglect nothing that would make certain the failure of Rossini’s opera.

Mme. Giorgi-Righetti reports that "hot-headed enemies" assembled at their posts as soon as the theatre opened, while Rossini’s friends, disappointed by the recent ill luck of "Torvaldo e Dorliska" were timid in their support of the new work. Furthermore, according to Mme. Giorgi Righetti, Rossini weakly yielded to a suggestion from Garcia, and permitted that artist, the Almaviva of the première, to substitute for the air which is sung under Rosina’s balcony, a Spanish melody with guitar accompaniment. The scene being laid in Spain, this would aid in giving local colour to the work -- such was the idea. But it went wrong. By an unfortunate oversight no one had tuned the guitar with which Almaviva was to accompany himself, and Garcia was obliged to do this on the stage. A string broke. The singer had to replace it, to an accompaniment of laughter and whistling. This was followed by Figaro’s entrance air. The audience had settled down for this. But when they saw Zamboni, as Figaro, come on the stage with another guitar, another fit of laughing and whistling seized them, and the racket rendered the solo completely inaudible. Rosina appeared on the balcony. The public greatly admired Mme. Giorgi-Righetti and was disposed to applaud her. But, as if to cap the climax of absurdity, she sung: "Segui, o caro, d’segui cosi" (Continue my dear, do always so). Naturally the audience immediately thought of the two guitars, and went on laughing, whistling, and hissing during the entire duet between Almaviva and Figaro. The work seemed doomed. Finally Rosina came on the stage and sang the "Una voce poco fa" (A little voice I heard just now) which had been awaited with impatience (and which today is still considered an operatic tour de force for soprano). The youthful charm of Mme. Girogi-Righetti, the beauty of her voice, and the favour with which the public regarded, her, "won her a sort of ovation" in this number. A triple round of prolonged applause raised hopes for the fate of the work. Rossini rose from his seat at the pianoforte, and bowed. But realizing that the applause was chiefly meant for the singer, he called to her in a whisper, "Oh, natura!" (Oh, human nature!)

"Give her thanks," replied the artiste, "since without her you would not have had occasion to rise from your seat."

What seemed a favorable turn of affairs did not, however, last long. The whistling was resumed louder than ever at the duet between Figaro and Rosina. "All the whistlers of Italy," says Castil-Blaze, "seemed to have given themselves a rendervous for his performance." Finally, a stentorian voice shouted: "This is the funeral of Don Pollione," words which doubtless had much spice for Roman ears, since the cries, the hisses, the stamping, continued with increased vehemence. When the curtain fell on the first act Rossini turned toward the audience, slightly shrugged his shoulders, and clapped his hands. The audience, though greatly offended by this show of contemptuous disregard for its opinion -- reserved its revenge for the second act, not a note of which it allowed to be heard.

At the conclusion of the outrage, for such it was, Rossini left the theatre with as much nonchalance as if the row had concerned the work of another. After they had gotten into their street clothes the singers hurried to his lodgings to condole with him. He was sound asleep!

There have been three historic failures of opera. One was the "Tannhäuser" fiasco, 1861; another, the failure of "Carmen," Paris, 1875. The earliest I have just described.

For the second performance of "Il Barbiere" Rossini replaced the unlucky air introduced by Garcia with the "Ecco ridente il cielo," as it now stands. This cavatina he borrowed from an earlier opera of his own, "Aureliano in Palmira" (Aurelian in Palmyra). It also had figured in a cantata (not an opera) by Rossini, "Ciro in Babilonia" (Cyrus in Babylon) -- so that measures first sung by a Persian king in the ancient capital of Nebuchadnezzar, and then by a Roman emperor and his followers in the city which fourished in an oasis in the Syrian desert, were found suitable to be intoned by a love-sick Spanish count of the seventeenth century as a serenade to his lady of Seville. It surely is amusing to discover in tracing this air to its original source, that "Ecco ridente il cielo" (Lo, smiles the morning in the sky) figured in "Aureliano in Palmira" as an address to Isis -- "Sposa del grande Osiride" (Spouse of the great Osiris).

Equally amusing is the relation of the overture to the opera. The original is said to have been lost. The present one has nothing to do with the ever-ready Figaro, the coquettish Rosina, or the sentimental Almaviva, although there have been writers who have dilated upon it as reflecting the spirit of the opera and its characters. It came from the same source as "Lo, smiles the morning in the sky" -- from "Aureliano," and, in between had figured as the overture to "Elisabetta, Regina d’Inghilterra." It is thus found to express in "Elisabetta" the conflict of love and pride in one of the most haughty souls of whom history records the memory, and in "Il Barbiere" the frolics of Figaro. But the Italians, prior to Verdi’s later period, showed little concern over such unfitness of things, for it is recorded that this overture, when played to "Il Barbiere," was much applauded.

"Ecco ridente il cielo," it is gravely pointed out by early writers on Rossini, is the "first example of modulation into the minor key later so frequently used by this master and his crowd of imitators." Also that "this ingenious way of avoiding the beaten path was not really a discovery of Rossini's, but belongs to Majo (an Italian who composed thirteen operas) and was used by several musician before Rossini." What a delightful pother over a modulation that the veriest tyro wound now consider hackneyed! However, "Ecco ridente," adapted in such haste to "Il Barbiere" after the failure of Garcia Spanish ditty, was sung by that artist the evening of the second performance, and loudly applauded. Moreover, Rossini had eliminated from his score everything that seemed to him to have been reasonably disapproved of. Then, pretending to be indisposed, he went to bed in order to avoid appearing at the pianoforte. The public, while not over-enthusiastic, received the work well on this second evening; and before long Rossini was accompanied to his rooms in triumph several evenings in succession, by the light of a thousand torches in the hands of the same Romans who had hissed his opera but a little while before. The work was first given under the title Rossini had insisted on, but soon changed back to that of the original libretto, "Il Barbiere di Siviglia."

It is a singular fact that the reception of "Il Baribiere" in Paris was much the same as in Rome. The first performance in the Salle Louvois was coldly received. Newspapers compared Rossini’s "Barber" unfavourably with that of Paisello. Fortunately the opposition demanded a revival of Paisiello’s work. Paer, musical director at the Théâtre Italien, not unwilling to spike Rossini’s guns, pretended to yield to a public demand, and brought out the earlier opera. But the opposite of what had been expected happened. The work was found to be superannuated. It was voted a bore. It scored a fiasco. Rossini triumphed . The elder Garcia, the Almaviva of the production in Rome, played the same role in Paris, as he also did in London, and at the first Italian performance of the work in New York.

Rossini had the reputation of being indolent in the extreme -- when he had nothing to do. We have seen that when the overture to "Il Barbiere di Siviglia" was lost (if he really ever composed one), he did not take the trouble to compose another, but replaced it with an earlier one. In the music lesson scene in the second act the original score is said to have contained a trio, presumably for Rosina, Almaviva, and Bartolo. This is said to have been lost with the overture. As with the overture, Rossini did not attempt to recompose this number either. He simply let his prima donna sing anything she wanted to. "Rosina sings an air, ad libitum, for the occasion," reads the direction in the libretto. Perhaps it was Giorgi-Righetti who first selected "La Biondina in gondoletta," which was frequently sung in the lesson scene by Italian prima donnas. Later there was substituted the air "Di tanti palpiti" from the opera "Tancredi," which is known as the "aria dei rizzi," or "rice aria," because Rossini, who was a great gourmet, composed it while cooking his rice. Pauline Viardot-Garcia (Garcia’s daughter), like her father in the unhappy première of the opera, sang a Spanish song. This may have been "La Calesera," which Adelina Patti also sang in Paris about 1867. Patti’s other selections at this time included the laughing song, the so-called "L’Eclat de Rire" (Burst of Laughter) from Auber’s "Manon Lescaut," as highly esteemed in Paris in years gone by as Massenet’s "Manon" now is. In New York I have heard Patti sing, in this scene, the Arditi waltz. "Il Bacio" (The Kiss); the bolero of Hélène, from "Les Vêpres Siciliennes" (The Sicilian Vespers), by Verdi; the "Shadow Dance" from Meyerbeer’s "Dinorah"; and, in concluding the scene, "Home, Sweet Home," which never failed to bring down the house, although the naïveté with which she sang it was more affected than affecting.

Among prima donnas much earlier than Patti there were at least two, Grisi and Alboni (after whom boxes were named at the Academy of Music) who adapted a brilliant violin piece, Rode’s "Air and Variations," to their powers of vocalization and sang it in the lesson scene. I mention this because the habit of singing an air with variations persisted until Mme Sembrich’s time. She sang those by Proch, a teacher of many prima donnas, among them Tietjens and Peschka-Leutner, who sang at the Peace Jubilee in Boston (1872) and was the first to make famous her teacher’s colorature variations, with ‘flauto concertante." Besides these variation, Mme. Sembrich sang Strauss’s "Voce di Primavera" waltz, "Ah! Non giunge," from "La Sonnambula," the bolero from "The Sicilian Vespers" and "O luce di quest anima," from "Linda di Chamounix." The scene was charmingly brought to an end by her seating herself at the pianoforte and singing, to her own accompaniment, Chopin’s "Maiden’s Wish." Mme. Melba sang Arditi’s waltz, "Se Saran Rose," Massenet’s "Sevillana," and the mad scene from "Lucia," ending, like Mme. Sembrich, with a song to which she played her own accompaniment, her choice being Tosti’s "Mattinata." Mme. Galli-Curci is apt to begin with the brilliant vengeance air from "The Magic Flute," her encores being "L’Eclat de Rire" by Auber and "Charmante Oiseau" (Pretty Bird) from David’s "La Perle du Brésil" (The Pearl of Brazil). "Home, Sweet Home" and "The Last Rose of Summer," both sung by her to her own accompaniment, conclude this interesting "lesson," in which every Rosina, although supposedly a pupil receiving a lesson, must be a most brilliant and accomplished prima donna.

The artifices of opera are remarkable. The most incongruous things happen. Yet because they do not occur in a drawing-room in real life, but on a stage separated from us by footlights, we lose all sense of their incongruity. The lesson scene occurs, for example, in an opera composed by Rossini in 1816. But the composition now introduced into that scene not only are not by Rossini but, for the most, are modern waltz songs and compositions entirely different from the class that a voice pupil, at the time the opera was composed, could possibly have sung. But so convincing is the fiction of the stage, so delightfully lawless its artifices, that these things do not trouble us at all. Mme. Galli-Curci, however, by her choice of the "Magic Flute" aria shows that it is entirely possible to select a work that already was a classic at the time "Il Barbiere" was composed, yet satisfies the demand of a modern audience for brilliant vocalization in this scene.

There is evidence that in the early history of "Il Barbiere," Rossini’s "Di tanti palpiti" (Ah! These heartbeats) from his opera "Tancredi" (Tancred), not only was invariably sung by prima donnas in the lesson scene, but that it almost became a tradition to use it in this scene. In September, 1821, but little more than five years after the work had its première, it was brought out in France (Grand Théâtre, Lyons) with French text by Castil-Blaze, who also superintended the publication of the score.

"I give this score," he says, "as Rossini wrote it. But as several pieces have been transposed to favour certain Italian opera singers, I do not consider it useless to point out these transpositions here . . . Air No. 10, written in G, is sung in A." Air No. 10 published by Castil-Blaze as an integral part of the score of "Il Barbiere," occurs in the lesson scene. It is "Di tanti palpiti" from "Tancredi."

Readers familiar with the history of opera, therefore aware that Alboni was a contralto, will wonder at her having appeared as Rosina, when that role is associated with prima donnas whose voices are extremely high and flexible. But the role was written for low voice. Giorgi-Righetti, the first Rosina, was a contralto. As it now is sung by high sopranos, the music of the role is transposed from the original to higher keys in order to give full scope for brilliant vocalization on high notes.

Many liberties have been taken by prima donnas in the way of vocal flourishes and a general decking out of the score of "Il Barbiere" with embellishments. The story goes that Patti once sang "Una voce poco fa," with her own frills added, to Rossini, in Paris.

"A very pretty song! Whose is it?" is said to have been the composer’s cutting comment.

There is another anecdote about "Il Barbiere" which brings in Donizetti, who was asked if he believed that Rossini really had composed the opera in thirteen days.

"Why not? He’s so lazy," is the reported reply.

If the story is true, Donizetti was a very forward young man. He was only nineteen when. "Il Barbiere" was produced, and had not yet brought out his first opera.

The first performance in America of "The Barber of Seville" was in English at the Park Theatre, New York; May 3, 1819. (May 17th, cited by some authorities, was the date of the third performance, and is so announced in the advertisements.) Thomas Philips was Almaviva and Miss Leesugg Rosina. "Report speaks in loud terms of the new opera called ‘The Barber of Seville’ which is announced for this evening. The music is said to be very splendid and is expected to be most effective." This primitive bit of "publicity," remarkable for its day, appeared in The Evening Post, New York, Monday, May 3, 1819. The second performance took place May 7th. Much music was interpolated. Phillips, as Almaviva, introduced "The Soldier’s Bride," "Robin Adair," "Pomposo, or a Receipt for an Italian Song," and "the favourite duet with Miss Leesugg, of ‘I love thee." (One wonders what was left of Rossini’s score). In 1821 he appeared again with Miss Holman as Rosina.

That Phillips should have sung Figaro, a baritone role in "Le Nozze di Figaro," and Almaviva, a tenor part, in "Il Barbiere," may seem odd. But in the Mozart opera he appeared in Bishop’s adaptation, in which the Figaro role is neither too high for a baritone, nor too low for a tenor. In fact the liberties Bishop took with Mozart’s score are so great (and so outrageous) that Phillips need have hesitated at nothing.

On Tuesday, November 22, 1825, Manuel Garcia, the elder, issued the preliminary announcement of his season of Italian opera at the Park Theatre, New York. The printers appear to have had a struggle with the Italian titles of operas and names of Italian composers. For The Evening Post announces that "The Opera of ‘H. Barbiora di Seviglia,’ by Rosina, is now in rehearsal and will be given as soon as possible." That "soon as possible" was the evening of November 29th, and is regarded as the date of the first performance in this country of opera in Italian.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-25 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |