Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > Die Walküre (Wagner) - Synopsis

Die Walküre - Synopsis

(English title: The Valkyrie)

An Opera by Richard Wagner

CHARACTERS

SIEGMUND……………………………….. Tenor

HUNDING………………………………… Bass

WOTAN………………………………….. Baritone-Bass

SIEGLINDE……………………………… Soprano

BRUNNHILDE………………………….. Soprano

FRICKA…………………………………. Mezzo-Soprano

Valkyrs (Sopranos and Mezzo-Sopranos): Gerhilde, Ortlinde, Waltraute, Schwertleite, Helmwige, Siegrune, Grimgerde, Rossweisse.

Time: Legendary.

Place: Interior of Hunding’s hut; a rocky height; the peak of a rocky mountain (the Brünnhilde rock).

Wotan’s enjoyment of Walhalla was destined to be shortlived. Filled with dismay by the death of Fasolt in the combat of the giants for the accursed ring, and impelled by a dread presentiment that the force of the curse would be visited upon the gods, he descended from Walhalla to the abode of the all-wise woman, Erda, who bore him nine daughters. These were the Valkyrs, headed by Brünnhilde -- the wild horsewomen of the air, who on winged steeds bore the dead heroes to Walhalla, the warriors’ heaven. With the aid of the Valkyrs and the heroes they gathered to Walhalla, Wotan hoped to repel any assault upon his castle by the enemies of the gods.

But though the host of heroes grew to a goodly number, the terror of Alberich’s curse still haunted the chief of gods. He might have freed himself from it had he returned the ring and helmet made of Rhinegold to the Rhinedaughters, from whom Alberich filched it; but in his desire to persuade the giants to relinquish Freia, whom he had promised to them as a reward for building Walhalla, he having wrested the ring from Alberich, gave it to the giants instead of returning it to the Rhinedaughters. He saw the giants contending for the possession of the ring and saw Fasolt slain -- the first victim of Alberich’s curse. He knows that the giant Fafner, having assumed the shape of a huge serpent, now guards the Nibelung treasure, which includes the ring and the Tarnhelmet, in a cave in the heart of a dense forest. How shall the Rhinegold be restored to the Rhinedaughters?

Wotan hopes that this may be consummated by a human hero who, free from the lust for power which obtains among the gods, shall, with a sword of Wotan’s own forging, slay Fafner, gain possession of the Rhinegold and restore it to its rightful owners, thus righting Wotan’s guilty act and freeing the gods from the curse. To accomplish this Wotan, in human guise as Wälse, begets, in wedlock with a human, the twins Siegmund and Sieglinde. How the curse of Alberich is visited upon these is related in "The Valkyr."

The dramatic personae in "The Valkyr" are Brünnhilde, the Valkyr, and her eight sister Valkyrs; Fricka, Sieglinde, Siegmund, Hunding (the husband of Sieglinde), and Wotan. The action begins after the forced marriage of Sieglinde to Hunding. The Wälsungs are in ignorance of the divinity of their father. They know him only as Wälse.

Act I. In the introduction to "The Rhinegold," we saw the Rhine flowing peacefully toward the sea and the innocent gambols of the Rhinedaughters. But "The Valkyr" opens in storm and stress. The peace and happiness of the first scene of the cycle seem to have vanished from the earth with Alberich’s abjuration of love, his theft of the gold, and Wotan’s equally treacherous acts.

This "Valkyr" Vorspiel is a masterly representation in tone of a storm gathering for its last infuriated onslaught. The elements are unleashed. The wind sweeps through the forest. Lightning flashes in jagged streaks across the black heavens. There is a crash of thunder and the storm has spent its force.

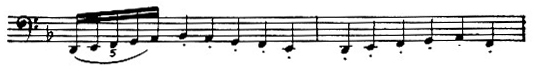

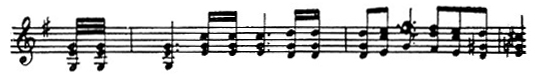

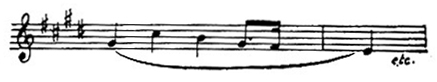

Two leading motives are employed in this introduction. They are the Storm Motive and the Donner Motive. The Storm Motive is as follows:

These themes are elemental. From them Wagner has composed storm music of convincing power.

In the early portion of this vorspiel only the string instruments are used. Gradually the instrumentation grows more powerful. With the climax we have a tremendous fortissimo on the contra tuba and two tympani, followed by the crash of the Donner Motive on the wind instruments.

The storm then gradually dies away. Before it has quite passed over, the curtain rises, revealing the large hall of Hunding’s dwelling. This hall is built around a huge ash-tree, whose trunk and branches pierce the roof, over which the foliage is supposed to spread. There are walls of rough-hewn boards, here and there hung with large plaited and woven hangings. In the right foreground is a large open hearth; back of it in a recess is the larder, separated from the hall by a woven hanging, half drawn. In the background is a large door. A few steps in the left foreground lead up to the door of an inner room. The furniture of the hall is primitive and rude. It consists chiefly of a table, bench, and stools in front of the ash-tree. Only the light of the fire on the hearth illumines the room; though occasionally its fitful gleam is slightly intensified by a distant flash of lightning from the departing storm.

The door in the background is opened from without. Siegmund, supporting himself with his hand on the bolt, stands in the entrance. He seems exhausted. His appearance is that of a fugitive who has reached the limit of his powers of endurance. Seeing no one in the hall, he staggers toward the hearth and sinks upon a bearskin rug before it, with the exclamation:

Whose hearth this may be,

Here I must rest me.

Wagner’s treatment of this scene is masterly. As Siegmund stands in the entrance we hear the Siegmund Motive. This is a sad, weary strain on ‘cellos and basses. It seems the wearier for the burden of an accompanying figure on the horns, beneath which it seems to stagger as Siegmund staggers toward the hearth. Thus the music not only reflects Siegmund’s weary mien, but accompanies most graphically his weary gait. Perhaps Wagner’s intention was more metaphysical. Maybe the burden beneath which the Siegmund Motive staggers is the curse of Alberich. It is through that curse that Siegmund’s life has been one of storm and stress.

When the storm-beaten Wälsung has sunk upon the rug the Siegmund Motive is followed by the Storm Motive, pianissimo -- and the storm has died away. The door of the room to the left opens and a young woman -- Sieglinde --- appears. She has heard someone enter, and, thinking her husband returned, has come forth to meet him-not impelled to this by love, but by fear. For Hunding had, while her father and kinsmen were away on the hunt, laid waste their dwelling and abducted her and fotrcibly married her. Ill-fated herself, she is moved to compassion at sight of the storm-driven fugitive before the hearth, and bends over him.

Her compassionate action is accompanied by a new motive, which by Wagner’s commentators has been entitled the Motive of Compassion. But it seems to me to have a further meaning as expressing the sympathy between two souls, a tie so subtle that it is at first invisible even to those who it unites. Siegmund and Sieglinde, it will be remembered, belong to the same race; and though they are at this point of the action unknown to one another, yet, as Sieglinde bends over the hunted, storm-beaten Siegmund, that subtle sympathy causes her to regard him with more solicitude than would be awakened by any other unfortunate stranger. Hence, I have called this motive the Motive of Sympathy -- taking sympathy in its double meaning of compassion and affinity of feeling.

The beauty of this brief phrase is enhanced by its unpretentiousness. It wells up from the orchestra as spontaneously as pity mingled with sympathetic sorrow wells up from the heart of a gentle woman. As it is Siegmund who has awakened these feelings in Sieglinde, the Motive of Sympathy is heard simultaneously with the Siegmund Motive.

Siegmund, suddenly raising his head, ejaculates, "Water, water!" Sieglinde hastily snatches up a drinking-horn and, having quickly filled it at a spring near the house, swiftly returns and hands it to Siegmund. As though new hope were engendered in Siegmund’s breast by Sieglinde’s gentle ministration, the Siegmund Motive rises higher and higher, gathering passion in its upward sweep and then, combined again with the Motive of Sympathy, sinks to an expression of heartfelt gratitude. This passage is scored entirely for strings. Yet no composer, except Wagner, has evoked from a full orchestra sounds richer or more sensuously beautiful.

Having quaffed from the proffered cup the stranger lifts a searching gaze to her features, as if they awakened within him memories the significance of which he himself cannot fathom. She, too, is strangely affected by his gaze. How has fate interwoven their lives that these two people, a man and a woman, looking upon each other apparently for the first time, are so thrilled by a mysterious sense of affinity?

Here occurs the Love Motive played throughout as a violoncello solo, with accompaniment of eight violoncellos and two double basses; exquisite in tone colour and one of the most tenderly expressive phrases ever penned.

The Love Motive is the mainspring of this act. For this act tells the story of love from its inception to its consummation. Similarly in the course of this act the Love Motive rises by degrees of intensity from an expression of the first tender presentiment of affection to the very ecstasy of love.

Siegmund asks with whom he has found shelter. Sieglinde replies that the house is Hunding’s, and she his wife, and requests Siegmund to await her husband’s return.

Weaponless am I:

The wounded guest,

He will surely give shelter,

is Siegmund’s reply. With anxious celerity, Sieglinde asks him to show her his wounds. But, refreshed by the draught of cool spring water and with hope revived by her sympathetic presence, he gathers force and, raising himself to a sitting posture, exclaims that his wounds are but slight; his frame is still firm, and had sword and shield held half so well, he would not have fled from his foes. His strength was spent in flight through the storm, but the night that sank on his vision has yielded again to the sunshine of Sieglinde’s presence. At these words the Motive of Sympathy rises like a sweet hope. Sieglinde fills the drinking-horn with mead and offers it to Siegmund. He asks her to take the first sip. She does so and then hands it to him. His eyes rest upon her while he drinks. As he returns the drinking-horn to her there are traces of deep emotion in his mien. He sighs and gloomily bows his head. The action at this point is most expressively accompanied by the orchestra. Specially noteworthy is an impassioned upward sweep of the Motive of Sympathy as Siegmund regards Sieglinde with traces of deep emotion in his mien

In a voice that trembles with emotion, he says: "You have harboured one whom misfortune follows wherever he wends his footsteps. Lest through me misfortune enter this house, I will depart." With firm, determined strides he already has reached the door, when she, forgetting all in the vague memories that his presence have stirred within her, calls after him:

"Tarry! You cannot bring sorrow to the house where sorrow already reigns!"

Her words are followed by a phrase freighted as if with sorrow, the Motive of the Wälsung Race, or Wälsung

Motive: Siegmund returns to the hearth, while she, as if shamed by her outburst of feeling, allows her eyes to sink toward the ground. Leaning against the hearth, he rests his calm, steady gaze upon her, until she again raises her eyes to his, and they regard each other in long silence and with deep emotion. The woman is the first to start. She hears Hunding leading his horse to the stall, and soon afterward he stands upon the threshold looking darkly upon his wife and the stranger. Hunding is a man of great strength and stature, his eyes heavy-browed, his sinister features framed in thick black hair and beard, a sombre, threatful personality boding little good to whonever crosses his path.

With the approach of Hunding there is a sudden change in the character of the music. Like a premonition of Hunding’s entrance we hear the Hunding Motive, pianissimo. Then as Hunding, armed with spear and shield, stands upon the threshold, this Hunding Motive -- as dark, forbidding, and portentous of woe to the two Wälsung as Hunding’s somber visage -- resounds with dread power on the tubas:

Although weaponless, and Hunding armed with spear and shield, the fugitive meets his scrutiny without flinching, while the woman, anticipating her husband’s inquiry, explains that she had discovered him lying exhausted at the hearth and given him shelter. With an assumed graciousness that makes him, if anything, more forbidding, Hunding orders her prepare the meal. While she does so he glances repeatedly from her to the stranger whom she has harboured, as if comparing their features and finding in them something to arouse his suspicions. "How like unto her," he mutters.

"Your name and story?" he asks, after they have seated themselves at the table in front of the ash-tree, and when the stranger hesitates, Hunding points to the woman’s eager, inquiring look.

"Guest," she urges, little knowing the suspicions her husband harbours, "gladly would I know whence you come."

Slowly, as if oppressed by heavy memories, he begins his story, carefully, however, continuing to conceal his name, since for all he knows, Hunding may be one of the enemies of his race. Amid incredible hardships, surrounded by enemies against whom he and his kin constantly were obliged to defend themselves, he crew up in the forest. He and his father returned from one of their hunts to find the hut in ashes, his mother a corpse, and no trace of his twin sister. In one of the combats with their foes he became separated from his father.

At this point you hear the Walhalla Motive, for Siegmund’s father was none othr than Wotan, known to his human descendants, however, only as Wälse. In Wotan’s narrative in the next act it will be discovered that Wotan purposedly created these misfortunes for Siegmund, in order to strengthen him for his task.

Continuing his narrative Siegmund says that, since losing track of his father, he has wandered from place to place, ever with misfortune in his wake. That very day he has defended a maid whom her brothers wished to force into marriage. But when, in the combat that ensued, he had slain her brothers, she turned upon him and denounced him as a murderer, while the kinsmen of the slain, summoned to vengeance, attacked him from all quarters. He fought until shield and sword were shattered, then fled to find chance shelter in Hunding‘s dwelling.

The story of Siegmund is told in melodious recitative. It is not a melody in the old-fashioned meaning of the term, but it fairly teems with melodiousness. It will have been observed that incidents very different in kind are related by Siegmund. It would be impossible to treat this narrative with sufficient variety of expression in a melody. But in Wagner’s melodious recitative the musical phrases reflect every incident narrated by Siegmund. For instance, when Siegmund tells how he went hunting with his father there is joyous freshness and abandon in the music, which, however, suddenly sinks to sadness as he narrates how they returned and found the Wälsung dwelling devastated by enemies. We hear also the Hunding Motive at this point, which thus indicates that whose who brought this misfortune upon the Wälsung were none other than Hunding and his kinsmen. As Siegmund tells how, when he was separated from his father, he sought to mingle with men and women, you hear the Love Motive, while his description of his latest combat is accompanied by the rhythm of the Hunding Motive. Those whom Siegmund slew were Hunding’s kinsmen. Thus Siegmund’s dark fate has driven him to seek shelter in the house of the very man who is the arch-enemy of his race and is bound by the laws of kinship to avenge on Siegmund the death of kinsmen.

As Siegmund concludes his narrative the Wälsung Motive is heard. Gazing with ardent longing toward Sieglinde, he says:

Now know’st thou, questioning wife,

Why "Peaceful" is not my name.

These words are sung to a lovely phrase. Then, as Siegmund rises and strides over to the hearth, while Sieglinde, pale and deeply affected by his tale, bows her head, there is heard on the horns, bassoons, violas, and ‘cellos a motive expressive of the heroic fortitude of the Wälsungs in struggling against their fate. It is the Motive of the Wälsung’s Heroism, a motive steeped in the tragedy of futile struggle against destiny.

The sombre visage at the head of the table has grown even darker and more threatening. Hunding arises. "I know a ruthless race to whom nothing is sacred, and hated of all," he says. "Mime were the kinsmen you slew. I too, was summoned from my home to take blood vengeance upon the slayer. Returning, I find him here. You have been offered shelter for the night, and for the night you are safe. But to-morrow be prepared to defend yourself."

Alone, unarmed, and in the house of his enemy! And yet the same roof harbours a friend -- the woman. What strange affinity has brought them together under the eye of the pitiless savage with whom she has been forced into marriage? The embers on the hearth collapse. The glow that for a moment pervades the room seems to his excited senses a reflection from the eyes of the woman to whom he has been so unaccountably yet to strongly drawn. Even the spot on the old ash-tree, where he saw her glance linger before she left the room, seems to have caught its sheen. Then the embers die out. All grows dark.

The scene is eloquently set to music., Siegmund’s gloomy thoughts are accompanied by the threatening rhythm of the Hunding Motive and the Sword Motive in a minor key, for Siegmund is still weaponless.

A sword my father did promise

Wälse! Wälse! Where is thy sword!

The Sword Motive rings out like a shout of triumph. As the embers of the fire collapse, there is seen in the glare, that for a moment falls upon the ash-tree, the gilt of a sword whose blade is buried in the trunk of the tree at the point upon which Sieglinde’s look last rested. While the Motive of the Sword gently rises and falls, like the coming and going of a lovely memory, Siegmund apostrophizes the sheen as the reflection of Sieglinde’s glance. And although the embers die out, and night falls upon the scene, in Siegmund’s thoughts the memory of that pitying, loving look glimmers on.

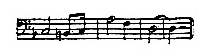

Is it his excited fancy that makes him hear the door of the inner chamber softy open and light footsteps coming in his direction? No; for he becomes conscious of a form, her form, dimly limned upon the darkness. He springs to his feet. Sieglinde is by his side. She has given Hunding a sleeping-potion. She will point out a weapon to Siegmund -- a sword. If he can wield it she will call him the greatest hero, for only the mightiest can wield it. The music quicknens with the subdued excitement in the breast of the two Wälsungs. You hear the Sword Motive and above it, on horns, clarinet, and oboe, a new motive -- that of the Wälsungs’ Call to Victory:

for Sieglinde hopes that with the sword the stranger, who has awakened so quickly love in her breast, will overcome Hunding. This motive has a resistless, onward sweep. Sieglinde, amid the strains of the stately Walhalla Motive, followed by the Sword Motive, narrates the story of the sword. While Hunding and his kinsmen were feasting in honour of her forced marriage with him, an aged stranger entered the hall. The men knew him not and shrank from his fiery glance. But upon her his look rested with tender compassion. With a mighty thrust he buried a sword up to its hilt in the trunk of the ash-tree. Whoever drew it from its sheath to him it should belong. The stranger went his way. One after another the strong men tugged at the hilt -- but in vain. Then she knew who the aged stranger was and for whom the word was destined.

The Sword Motive rings out like a joyous shout, and Sieglinde’s voice mingles with the triumphant notes of the Wälsung’s Call to Victory as she turns to Siegmund:

O, found I in thee

The friend in need!

The Motive of the Wälsung’s heroism, now no longer full of tragic import, but forceful and defiant -- and Siegmund holds Sieglinde in his embrace.

There is a rush of wind. The woven hangings flap and fall. As the lovers turn, a glorious sight greets their eyes. The landscape is illuminated by the moon. Its silver sheen flows down the hills and quivers along the meadows whose grasses tremble in the breeze. All nature seems to be throbbing in unison with the hearts of the lovers, and, turning to the woman, Siegmund greets her with the Love Song:

The Love Motive, impassioned, irresistible, sweeps through the harmonies -- and Love and Spring are united. The Love Motive also pulsates through Sieglinde’s ecstatic reply after she has given herself fully up to Siegmund in the Flight Motive -- for before his coming her woes have fled as winter flies before the coming of spring. With Siegmund’s exclamation:

Oh, wondrous vision!

Rapturous woman!

there rises from the orchestra like a vision of loveliness the Motive of Freia, the Venus of German mythology. In its embrace it folds this pulsating theme:

It throbs on like a love-kiss until it seemingly yields to the blandishments of this caressing phrase:

This throbbing, pulsating, caressing music is succeeded by a moment of repose. The woman again gazes searchingly into the man’s features. She has seen his face before. When? Now she remembers. It is when she has seen her own reflection in a brook! And his voice? It seems to her like an echo of her own. And his glance; has it never before rested on her? She is sure it has, and she will tell him when.

She repeats how, while Hunding and his kinsmen were feasting at her marriage, an aged man entered the hall and, drawing a sword thrust it to the hilt in the ash-tree. The first to draw it out, to him it should belong. One after another the men strove to loosen the sword, but in vain. Once the aged man’s glance rested on her and shone with the same light as now shines in his who has come to her through night and storm. He who thrust the sword into the tree was of her own race, the Wälsungs. Who is he?

"I, too, have seen that light, but in your eyes!" exclaimed the fugitive. "I, too, am of your race. I, too, am a Wälsung, my father none other than Wälse himself."

"Was Wälse your father?" she cries ecstatically. "For you, then, this sword was thrust in the tree! Let me name you, as I recall you from far back in my childhood, Siegmund -- Siegmund -- Siegmund!"

"Yes, I am Siegmund; and you, too, I now know well. You are Sieglinde. Fate has willed that we two of our unhappy race, shall meet again and save each other or perish together."

Then, leaping upon the table, he grasps the sword-hilt which protrudes from the trunk of the ash-tree where he has seen that strange glow in the light of the dying embers. A mighty tug, and he draws it from the tree as a blade from its scabbard. Brandishing it in triumph, he leaps to the floor, and, clasping Sieglinde, rushes forth with her into the night.

And the music? It fairly seethes with excitement. As Siegmund leaps upon the table, the Motive of the Wälsung’s Heroism rings out as if in defiance of the enemies of the race. The Sword Motive -- and he has grasped the hilt; the Motive of Compact, ominous of the fatality which hangs over the Wälsungs; the Motive of Renunciation, with its threatening import; then the Sword Motive -- brilliant like the glitter of refulgent steel -- and Siegmund has unsheathed the sword. The Wälsungs’ Call to Victory, like a song of triumph; a superb upward sweep of the Sword Motive; the Love Motive, now rushing onward in the very ecstasy of passion, and Siegmund holds in his embrace, Sieglinde, his bride -- of the same doomed race as himself!

Act II. In the Vorspiel the orchestra, with an upward rush of the Sword Motive, resolved into 9-8 time, the orchestra dashes into the Motive of Flight. The Sword Motive in this 9-8 rhythm closely resembles the Motive of the Valkyr’s Ride, and the Flight Motive in the version in which it appears is much like the Valkyr’s Shout. The Ride and the Shout are heard in the course of the Vorspiel, the former with tremendous force on trumpets and trombones as the curtain rises on a wild, rocky mountain pass, at the back of which, through a natural rock-formed arch, a gorge slopes downward.

In the foreground stands Wotan, armed with spear, shield, and helmet. Before him is Brünnhilde in the superb costume of the Valkyr. The stormy spirit of the Vorspiel pervades the music of Wotan’s command to Brünnhilde that she bridle her steed for battle and spur it to the fray to do combat for Siegmund against Hunding. Brünnhilde greets Wotan’s commands with the weirdly joyous Shout of the Valkyrs.

Hojotoho! Heiaha-ha.

It is the cry of the wild horsewomen of the air, coursing through storm-clouds, their shields flashing back the lightning, their voices mingling with the shrieks of the tempest. Weirder, wilder joy has never found expression in music. One seems to see the steeds of the air and streaks of lightning playing around their riders, and to hear the whistling of the wind.

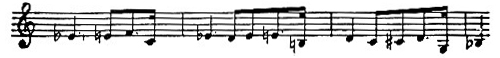

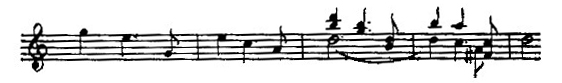

The accompanying figure is based on the Motive of the Ride of the Valkyrs:

Brünnhilde, having leapt from rock to rock to the highest peak of the mountain, again faces Wotan, and with delightful banter calls to him that Fricka is approaching in her ram-drawn chariot. Fricka has appeared, descended from her chariot, and advances toward Wotan, Brünnhilde having meanwhile disappeared behind the mountain height,

Fricka is the protector of the marriage vow, and as such she has come in anger to demand from Wotan vengeance in behalf of Hunding. As she advances hastily toward Wotan, her angry, passionate demeanour is reflected by the orchestra, and this effective musical expression of Fricka’s ire is often heard in the course of the scene. When near Wotan she moderates her pace, and her angry demeanour gives way to sullen dignity.

Wotan, though knowing well what has brought Fricka upon the scene, feigns ignorance of the cause of her agitation and asks what it is that harasses her. Her reply is preceded by the stern Hunding motive. She tells Wotan that she, as the protectress of the sanctity of the marriage vow, has heard Hunding’s voice calling for vengeance upon the Wälsung twins. Her words, "His voice for vengeance is raised," are set to a phrase strongly suggestive of Alberich’s curse. It seems as though the avenging Nibelung were pursuing Wotan’s children and thus striking a blow at Wotan himself through Fricka. The Love Motive breathes through Wotan’s protest that Siegmund and Sieglinde only yielded to the music of the spring night. Wotan argues that Siegmund and Sieglinde are true lovers, and Fricka should smile instead of venting her wrath on them. The motive of the Love Song, the Love Motive, and the caressing phrase heard in the love scene are beautifully blended with Wotan’s words. In strong contrast to these motives is the music in Fricka’s outburst of wrath, introduced by the phrase reflecting her ire, which is repeated several times in the course of this episode. Wotan explains to her why he begat the Wälsung race and the hopes he has founded upon it. But Fricka mistrusts him. What can mortals accomplish that the gods, who are far mightier than mortals, cannot accomplish? Hunding must be avenged on Siegmund and Sieglinde. Wotan must withdraw his protection from Siegmund. Now appears a phrase which expresses Wotan’s impotent wrath -- impotent because Fricka brings forward the unanswerable argument that if the Wälsungs go unpunished by her, as guardian of the marriage vow, she, the Queen of the Gods, will be held up to the scorn of mankind.

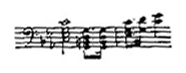

Wotan would fain save the Wälsungs. But Fricka’s argument is conclusive. He cannot protect Siegmund and Sieglinde, because their escape from punishment would bring degradation upon the queen-goddess and the whole race of the gods, and result in their immediate fall. Wotan’s wrath rises at the thought of sacrificing his beloved children to the vengeance of Hunding, but he is impotent. His far-reaching plans are brought to nought. He sees the hope of having the Ring restored to the Rhinedaughters by the voluntary act of a hero of the Wälsung race vanish. The curse of Alberich hang over him like a dark, threatening cloud. The Motive of Wotan’s Wrath is as follows:

Brünnhilde’s joyous shouts are heard from the height. Wotan exclaims that he had summoned the Valkyr to do battle for Siegmund. In broad, stately measures, Fricka proclaims that her honour shall be guarded by Brünnhilde’s shield and demands of Wotan an oath that in the coming combat the Wälsung shall fall. Wotan takes the oath and throws himself dejectedly down upon a rocky seat. Fricka strides toward the back. She pauses a moment with a gesture of queenly command before Brünnhilde, who has led her horse down the height and into a cave to the right, then departs.

In this scene we have witnessed the spectacle of a mighty god vainly struggling to avert ruin from his race. That it is due to irresistible fate and not merely to Fricka that Wotan’s plans succumb, is made clear by the darkly ominous notes of Alberich’s Curse, which resounds as Wotan, wrapt in gloomy brooding, leans back against the rocky seat, and also when, in a paroxysm of despair, he gives vent to his feelings, a passage which, for overpowering intensity of expression, stands out even from among Wagner’s writings. The final words of this outburst of grief:

The saddest I among all men.

are set to this variant of the Motive of Renunciation; the meaning of this phrase having been expanded from the renunciation of love by Alberich to cover the renunciation of happiness which is forced upon Wotan by avenging fate:

Brünnhilde casts away shield, spear, and helmet, and sinking down at Wotan’s feet looks up to him with affectionate anxiety. Here we see in the Valkyr the touch of tenderness, without which a truly heroic character is never complete.

Musically it is beautifully expressed by the Love Motive, which, when Wotan, as if awakening from a reverie, fondly strokes her hair, goes over into the Siegmund Motive. It is over the fate of his beloved Wälsungs Wotan has been brooding. Immediately following Brünnhilde’s words,

What am I were I not thy will,

is a wonderfully soft yet rich melody on four horns. It is one of those beautiful fetails in which Wagner’s works abound.

In Wotan’s narrative, which now follows, the chief of the gods tells Brünnhilde of the events which have brought this sorrow upon him, of his failure to restore the stolen gold to the Rhinedaughters; of his dread of Alberich’s curse; how she and her sister Valkyrs were born to him by Erda; of the necessity that a hero should without aid of the gods gain the Ring and Tarnhelmet from Fafner and restore the Rhinegold to the Rhinedaughters; how he begot the Wälsungs and inured them to hardships in the hope that one of the race would free the gods from Alberich’s curse.

The motives heard in Wotan’s narrative will be recognized, except one, which is new. This is expressive of the stress to which the gods are subjected through Wotan’s crime. It is first heard when Wotan tells of the hero who alone can regain the ring. It is the Motive of the Gods’ Stress.

Excited by remorse and despair Wotan bids farewell to the glory of the gods. Then he in terrible mockery blesses the Nibelung’s heir -- for Alberich has wedded and to him has been born a son, upon whom the Nibelung depends to continue his death struggle with the gods. Terrified by this outburst of wrath, Brünnhilde asks what her duty shall be in the approaching combat. Wotan commands her to do Fricka’s bidding and withdraw protection from Siegmund. In vain Brünnhilde pleads for the Wälsung whom she knows Wotan loves, and wished a victor until Fricka exacted a promise from him to avenge Hunding. But her pleading is in vain. Wotan is no longer the all-powerful chief of the gods -- through his breach of faith he has become the slave of fate. Hence we hear, as Wotan rushes away, driven by chagrin, rage, and despair, chords heavy with the crushing force of fate.

Slowly and sadly Brünnhilde bends down for her weapons, her actions being accompanied by the Valkyr Motive. Bereft of its stormy impetuosity it is as trist as her thoughts. Lost in sad reflections, which find beautiful expression in the orchestra, she turns toward the background.

Suddenly the sadly expressive phrases are interrupted by the Mnotive of Flight. Looking down into the valley the Valkyr perceives Siegmund and Sieglinde approaching in hasty flight. She then disappears in the cave. With a superb crescendo the Motive of Flight reaches its climax and the two Wälsungs are seen approaching through the natural arch. For hours they have toiled forward; often Sieglinde’s limbs have threatened to fail her, yet never have the fugitives been able to shake off the dread sound of Hunding winding his horn as he called upon his kinsmen to redouble their efforts to overtake the two Wälsungs. Even now, as they come up the gorge and pass under a rocky arch to the height of the divide, the pursuit can be heard. They are human quarry of the hunt. Terror has begun to unsettle Sieglinde’s reason. When Siegmund bids her rest the stares wildly before her, then gazes with growing rapture into his eyes and throws her arms around his neck, only to shriek suddenly: "Away, away!" as she hears the distant horn-calls, then to grow rigid and stare vacantly before her as Siegmund announces to her that here he proposes to end their flight, here await Hunding, and test the temper of Wälse’s sword. Then she tries to thrust him away. Let him leave her to her fate and save himself. But a moment later, although she still clings to him, she apparently is gazing into vacancy and crying out that he has deserted her. At last, utterly overcome by the strain of flight with the avenger on the trail, she faints, her hold on Siegmund relaxes, and she would have fallen had he not caught her form in his arms. Slowly he lets himself down on a rocky seat, drawing her with him, so that when he is seated her rests on his lap. Tenderly he looks down upon the companion of his flight, and, while like a mournful memory, the orchestra intones the Love Motive, he presses a kiss upon her brow -- she of his own race, like him doomed to misfortune, dedicated to death, should the sword which he has unsheathed from Hunding’s ash-tree prove traitor. As he looks up from Sieglinde he is startled. For there stands on the rock above them a shining apparition in flowing robes, breast-plate, and helmet, and leaning upon a spear. It is Brünnhilde, the Valkyr, daughter of Wotan.

The Motive of Fate -- so full of solemn import -- is heard.

While her earnest look rests upon him, there is heard the Motive of the Death-Song, a tristly prophetic strain.

Brünnhilde advances and then, pausing again, leans with one hand on her charger’s neck, and, grasping shield and spear with the other, gazes upon Siegmund. Then there rises from the orchestra, in strains of rich, soft, alluring beauty, an inversion of the Walhalla Motive. The Fate, Death-Song and Walhalla motives recur, and Siegmund, raising his eyes and meeting Brünnhilde’s look, questions her and receives her answers. The episode is so fraught with solemnity that the shadow of death seems to have fallen upon the scene. The solemn beauty of the music impresses itself the more upon the listener, because of the agitated, agonized scene which preceded it. To the Wälsung, who meets her gaze so calmly, Brünnhilde speaks in solemn tones:

"Siegmund, look on me. I am she whom soon you must prepare to follow." Then she paints for him in glowing colours the joys of Walhalla, where Wälse, his father, is awaiting him and where he will have heroes for his companions, himself the hero of many valiant deeds. Siegmund listens unmoved. In reply he frames but one question: "When I enter Walhalla, will Sieglinde be there to greet me?"

When Brünnhilde answers that in Walhalla he will be attended by valkyrs and wishmaidens, but that Sieglinde will not be there to meet him, he scorns the delights she has held out. Let her greet Wotan from him, and Wälse, his father, too, as well as the wishmaidens. He will remain with Sieglinde.

Then the radiant Valkyr, moved by Siegmund’s calm determination to sacrifice even a place among the heroes of Walhalla for the woman he loves, makes known to him the fate, to which he has been doomed. Wotan desired to give him victory over Hunding, and she had been summoned by the chief of the gods and commanded to hover above the combatants, and by shielding Siegmund from Hunding’s thrusts, render the Wälsung’s victory certain. But Wotan’s spouse, Fricka, who, as the first among the goddesses, is guardian of the marriage vows, has heard Hunding’s voice calling for vengeance, and has demanded that vengeance be his. Let Siegmund therefore prepare for Walhalla, but let him leave Sieglinde in her care. She will protect her.

"No other living being but I shall touch her," exclaims the Wälsung, as he draws his sword. "If the Wälsung sword is to be shattered on Hunding’s spear, to which I am to fall a victim, it first shall bury itself in her breast and save her from a worse fate!" He poises the sword ready for the thrust above the unconscious Sieglinde.

"Hold!" cries Brünnhilde, thrilled by his heroic love. "Whatever the consequences which Wotan, in his wrath, shall visit upon me, to-day, for the first time I disobey him. Sieglinde shall live, and with her Siegmund! Yours the victory over Hunding. Now Wälsung, prepare for battle!"

Hunding’s horn-calls sound nearer and nearer. Siegmund judges that he has ascended the other side of the gorge, intending to cross the rocky arch. Already Brünnhilde has gone to take her place where she knows the combatants must meet. With a last look and a last kiss for Sieglinde, Siegmund gently lays her down and begins to ascend toward the peak. Mist gathers’ storm-clouds roll over the mountain; soon he is lost to sight. Slowly Sieglinde regains her scenes. She looks for Siegmund. Instead of seeing him bending over her she hears Hunding’s voice as if from among the clouds, calling him to combat; then Siegmund’s accepting the challenge. She staggers toward the peak. Suddenly a bright light pierces the clouds. Above her she sees the men fighting, Brünnhilde protecting Siegmund who is aiming a deadly stroke at Hunding.

At that moment, however, the light is diffused with a reddish glow. In it Wotan appears. As Siegmund’s sword cuts the air on its errand of death, the god interposes his spear, the sword breaks in two and Hunding thrusts his spear into the defenceless Wälsung’s breast. The second victim of Alberich’s curse has met his fate.

With a wild shriek, Sieglinde falls to the ground, to be caught up by Brünnhilde and swung upon the Valkyr’s charger, which, urged on by its mistress, now herself a fugitive from Wotan’s anger, dashes down the defile in headlong flight for the Valkyr rock.

Act III. The third act opens with the famous "Ride of the Valkyrs," a number so familiar that detailed reference to it is scarcely necessary. The wild maidens of Walhalla coursing upon winged steeds through storm-clouds, their weapons flashing in the gleam of lightning, their weird laughter mingling with the crash of thunder, have come to hold tryst upon the Valkyr rock.

When eight of the Valkyrs have gathered upon the rocky summit of the mountain, they espy Brünnhilde approaching. It is with savage shouts of "Hojotoho! Heiha!" those who already have reached their savage eyrie, watch for the coming of their wild sisters. Fitful flashes of lightning herald their approach as they storm fearlessly through the wind and cloud, their weird shouts mingling with the clash of thunder. "Hojotoho! Heihe! -- Hojotoho! Heiha!"

But, strange burden! Instead of a slain hero across her pommel, Brünnhilde bears a woman, and instead of urging her horse to the highest crag, she alights below. The Valkyrs hasten down the rock, and there the wild sisters of the air stand, curiously awaiting the approach of Brünnhilde.

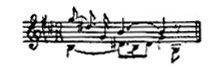

In frantic haste the Valkyr tells her sisters what has transpired, and how Wotan is pursuing her to punish her for her disobedience. One of the Valkyrs ascends the rock and, looking in the direction from which Brünnhilde has come, calls out that even now she can descry the red glow behind the storm-clouds that denotes Wotan’s approach. Quickly Brünnhilde bids Sieglinde seek refuge in the forest beyond the Valkyr rock. The latter, who has been lost in gloomy brooding, starts at her rescuer’s supplication and in strains replete with mournful beauty begs that she may be left to her fate and follow Siegmund in death. The glorious prophecy in which Brünnhilde now foretells to Sieglinde that she is to become the mother of Siegfried, is based upon the Siegfried Motive:

Sieglinde, in joyous frenzy, blesses Brünnhilde and hastens to find safety in a dense forest to the eastward, the same forest in which Fafner, in the form of a serpent, guards the Rhinegold treasures.

Wotan, in hot pursuit of Brünnhilde, reaches the mountain summit. In vain her sisters entreat him to spare her. He harshly threatens them unless they cease their entreaties, and with wild cries of fear they hastily depart.

In the ensuing scene between Wotan and Brünnhilde, in which the latter seeks to justify her action, is heard one of the most beautiful themes of the cycle.

It is the Motive of Brünnhilde’s Pleading, which finds its loveliest expression when she addresses Wotan in the passage beginning:

Thou, who this love within my breast inspired.

Brünnhilde is Wotan’s favourite daughter, but instead of the loving pride with which he always has been wont to regard her, his features are dark with anger at her disobedience of his command. He had decreed Siegmund’s death. She has striven to give victory to the Wälsung. Throwing herself at her father’s feet, she pleads that he himself had intended to save Siegmund and had been turned from his purpose only by Fricka’s interference, and that he had yielded only most grudgingly to Fricka’s insistent behest. Therefore, when she, his daughter, profoundly moved by Siegmund’s love for Sieglinde, and her sympathies aroused by the sad plight of the fugitives, disregarded his command, she nevertheless acted in accordance with his real inclinations. But Wotan is obdurate. She has reveled in the very feelings which he was obliged, at Fricka’s behest, to forego -- admiration for Siegmund’s heroism and sympathy for him in his misfortune. Therefore she must be punished. He will cause her to fall into a deep sleep upon the Valkyr rock, which shall become the Brünnhilde rock, and to the first man who finds her and awakens her, she no longer a Valkyr, but a mere woman, shall fall prey.

This great scene between Wotan and Brünnhilde is introduced by an orchestral passage. The Valkyr lies in penitence at her father’s feet. In the expressive orchestral measures the Motive of Wotan’s Wrath mingles with that of Brünnhilde’s Pleading. The motives thus form a prelude to the scene in which the Valkyr seeks to appease her father’s anger, not through a specious plea, but by laying bare the prompting of a noble heart, which forced her, against the chief god’s command, to intervene for Siegmund. The Motive of Brünnhilde’s Pleading is heard in its simplest form at Brünnhilde’s words:

Was it so shameful what I have done,

and it may be noticed that as she proceeds the Motive of Wotan’s Wrath, heard in the accompaniment, grows less stern, until with her plea,

Soften they wrath,

it assume a tone of regretful sorrow.

Wotan’s feeling toward Brünnhilde have softened for the time from anger to grief that he must mete out punishment for the disobedience. In this reply excitement subsides to gloom. It would be difficult to point to other music more touchingly expressive of deep contrition than the phrase in which Brünnhilde pleads that Wotan himself taught her to love Siegmund. It is here that the Motive of Brünnhilde’s Pleading assumes the form in the notation given above. Then we hear from Wotan that he had abandoned Siegmund to his fate, because he had lost hope in the cause of the gods and wished to end his woe in the wreck of the world. The weird terror of the Curse Motive hangs over this outburst of despair. In broad and beautiful strains Wotan then depicts Brünnhilde yielding to her emotions when she intervened for Siegmund.

Brünnhilde makes her last appeal. She tells her father that Sieglinde has found refuge in the forest, and that there she will give birth to a son, Siegfried, - -- the hero of whom the gods have been waiting to overthrow their enemies. If she must suffer for her disobedience, let Wotan surround her sleeping form with a fiery circle which only such a hero will dare penetrate. The Motive of Brünnhilde’s Pleading and the Siegfried Motive vie with each other in giving expression to the beauty, tenderness, and majesty of this scene.

Gently the god raises her and tenderly kisses her brow: and thus bids farewell to the best beloved of his daughters. Slowly she sinks upon the rock. He closes her helmet and covers her with her shield. Then, with his spear, he invokes the god of fire. Tongues of flame leap from the crevices of the rock. Wildly fluttering fire breaks out on all sides. The forest beyond glows like a furnace, with brighter streaks shooting and throbbing through the mass, as Wotan, with a last look at the sleeping form of Brünnhilde, vanishes beyond the fiery circle.

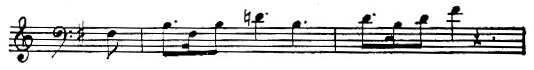

A majestic orchestral passage kopens Wotan’s farewell to Brünnhilde. In all music for bass voice this scene has no peer. Such tender, mournful beauty has never found expression in music -- and this, whether we regard the vocal part or the orchestral accompaniment in which the lovely Slumber Motive:

As Wotan leads Brünnhilde to the rock, upon which she sinks, closes her helmet, and covers her with her shield, then invokes Loge, and, after gazing fondly upon the slumbering Valkyr, vanishes amid the magic flames, the Slumber Motive, the Magic Fire Motive, and the Siegfried Motive combine to place the music of the scene with the most brilliant and beautiful portion of our heritage from the great master-musician. But here, too, lurks Destiny. Towards the close of this glorious finale we hear again the ominous muttering of the Motive of Fate. Brünnhilde may be saved from ignominy, Siegfried may be born to Sieglinde -- but the crushing weight of Alberich’s curse still rests upon the race of the gods.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-25 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |