Music with Ease > 19th Century French Opera > Faust (Gounod)

Faust

An Opera by Charles François Gounod

Many versions of the Faust legend exist, but only two count as literature -- those of Christopher Marlowe and Goethe. Goethe’s is the incomparable creation. The spell of the ancient apologue laid hold of him before he was well out of his teens. "The marionette fable of Faust," he says, "murmured with many voices in my soul. I, too, had wandered into every department of knowledge, and had returned early enough satisfied with the vanity of science. And life, too, I had tried under various aspects, and always came back sorrowing and unsatisfied." The first part of his great work was published in 1808, the second in 1831. From it the "Faust" of Gounod, a work equally great in its own way, is essentially derived.

A French statistician has proved that more composers have been inspired by Goethe’s master creation than by any other secular piece of literature whatsoever. He gives a list of no fewer than nineteen operas written on the subject, beginning with the 1810 setting of Spohr (a "conscientious work," now forgotten), and ending with the "Faust" of Lassen, produced at Weimar in 1876. To these might be added Berlioz’s fantastic La Damnation de Faust, Schumann’s mystic symphonic work, Liszt’s "Faust" symphony, and a "Faust" overture written by Wagner in 1849. It is said that Beethoven thought of crowning his career by a "Faust" -- and what a "Faust" that would have been! Rossini, too, had hoped to measure himself with Goethe, and Alexandre Dumas was to have written the words. To opera-goers, however, there is but one "Faust," and it is that which figures in the Frenchman’s list as by "Charles Gounod, Paris, 1859."

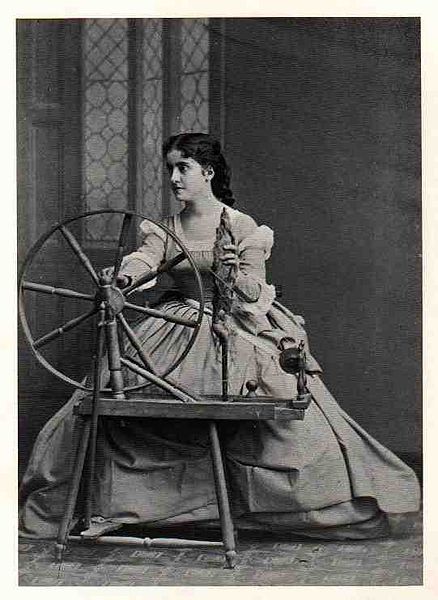

Soprano opera singer, Adelina Patti (1843-1919), as Marguerite in Charles Gounod's Faust

THE LIBRETTO

No composer could hope to deal with the entire Faust legend as it is enshrined in Goethe’s vast and complex conception. One composer will fix on this, another will fix on that, according as his genius and his personal fancy dictate. Gounod and his librettists fixed on the single episode of Gretchen, as illustrating the eternal legend of love, its allurements, betrayals, ardours, and tortures, and practically discarded the rest of the mighty drama. The fantastic element was purposely, and rightly, subordinated to the human. In Madame de Bovet’s "Life of Gounod" there is a very interesting passage giving, in effect, the result of a conversation which the writer had with Jules Barbier, the chief librettist. What in his eyes, we gather, made this particular episode of "Faust" the paragon of dramatic plots was its simplicity and its very ordinary action, which is the only eternal one.

It is the drama of the heart which, since the beginning of the world, has been enacted between three characters, the man, the woman, and the devil; the last being the personification of original sin, if we use the Christian phraseology, or to place the question on freer ground, of passion implanted by nature in the heart and senses of the two other ones. The man attracted to the woman by the strength of desire; the woman falling into his arms under the impulse of the Satanic tempter; the selfishness of the one, the self-abnegation of the other, are the elements of the drama. The idealisation, the transfiguration by love of a lowly being -- for Margaret is but a serving-wench, says M. Barbier, with a roughness of expression which is strictly true -- is the second; the third is the purification by suffering of a soul stained by the baseness of humanity.

The subject is sufficiently grand. Who will seriously affirm, the objectors notwithstanding, that it would be improved by additional philosophical developments in which poetry might be submerged and music wrecked, or by the fanciful additions which after all are manipulations rather than inspirations and more ostentatious than valuable? Gounod’s librettists made no pretensions to high literary skill, but they knew what was required of them. Their task was to adapt Goethe’s work to the requirements of lyric drama, and they performed the task with equal taste and intelligence. "A well-constructed and thoroughly comprehensible libretto, with plenty of love-making and floods of cheap sentiment," is the verdict of one who may claim to speak as an authority. Let us see, then, what the story exactly is as it unwinds itself in association with Gounod’s music.

ACT 1. -- One the soul of Faust has fallen a mood of deep depression. We see him seated in his study, sick to death of the learned lore he has been pursuing, weary and disillusioned of the pettiness and the triviality of life; ready to "take arms" against himself and end it all by the poison which has stood forgotten on his shelf for years. He is just about to raise the vial to his lips when the distant chorus of the angels breaks on his ear. Softer and better thoughts come back to him, and he drops the fatal draught. But melancholy soon supervenes. In despair he invokes the aid of the infernal powers. Somewhat to his surprise, Mephistopheles, the embodiment of the Evil One, promptly appears, arrayed in the garb of a travelling student, which is presently replaced by the scarlet dress and cap with the cock’s feather so familiar to us on the stage. The Evil One promises to endow Faust with all sorts of good fortune -- with youth, and elegance of form, and fine adornments, and love, and a host of other things -- if only Faust will give himself, body and soul, in exchange. To hasten his decision, the tempter shows Faust, as an earnest of future "favours," a mirror-vision of the lovely village maiden, seated at her spinning-wheel, who is to play such a tragic part in his history. Margaret’s charms take complete possession of Faust’s heart, and, with his own blood, he signs the contract drawn by the Prince of Darkness. After drinking a magic philtre which endows him with youth and beauty and splendid attire, he hurries away with his demon-companion, and the Act closes.

ACT 2. -- his Act we find that Mephistopheles has carried Faust to a Kermesse in the market-place of a country town. Valentine now goes off to the wars, distressed at leaving, "alone and young," his sister Margaret. His friend Siebel, a boyish admirer, promises to "guard her like a brother." Valentine leaves her, however, to the care of Dame Martha, a kindly, but vulgar, commonplace woman, who proved a by no means vigilant person. Faust now pleads with Mephistopheles to see Margaret, "that darling child whom I saw in a dream." Mephistopheles agrees to his request; and so, during a break in the dances, Faust is enabled to salute Margaret for the first time as she returns from church. He offers her his escort, which she declines; whereupon Mephistopheles observes that he must teach Faust how to woo, and the dance is resumed.

ACT 3. -- This Act takes place in Margaret’s garden. Siebel has left a floral offering for Margaret. Faust and Mephistopheles enter secretly and place "something a little rarer, to adorn a too willing wearer," namely, a casket of jewels, on the doorstep. The beauty of the jewels overcomes her woman’s weakness. As Mephistopheles says, "If yonder flowers this casket do outshine, never will I trust a woman more." Never in her sleep did Margaret dream of anything so lovely. She cannot resist putting on the jewels. Faust and Mephistopheles find her adorned with them, and while Mephistopheles keeps Martha, the convenient neighbour in whose house Margaret is often found, out of the way, Faust passionately pleads his love with Margaret. The Act ends by Margaret "yielding to Faust’s prayers and entreaties," as the euphemism is. In plain terms, Margaret has lost her virtue.

ACT 4. -- We now see Margaret left alone, disconsolate, shunned by her friends, haunted by remorse. Faust has thrown her aside. He has, however, to reckon with Valentine, who returns from his military service to learn, from the scandal of the town, of his sister’s love affair. His sister has been his pride, and he must be revenged. Discovering, in the grey of the morning, the false Faust skulking under Margaret’s window, he challenges the seducer to a duel. The white blades cross in the faint light. Faust’s Satanic second lends strength to his arm, and Valentine falls. He dies in Margaret’s arms, denouncing her secret guilt to the crowd that has gathered around. It is during this Act that the "church scene" occurs -- sometimes performed after Valentine’s death, sometimes before it. Margaret is on her knees in the dim religious light of the minster, striving to direct her thoughts in prayer, a guilty conscience stifling her half-formed utterances. The madness of love has passed; the pain of betrayal has cooled the ardour of passion, leaving the soul of Margaret crushed under the weight of sin, tortured by regret and remorse. She is forsaken by the Deity so that she may wash the stain of her guilt in the waters of repentance. The "gentle creature," as the poem calls her, struggles against the demon bent on his prey.

ACT 5. -- Margaret’s reason is unseated; grief has driven her insane. In her frenzy she has murdered her babe. She is thrown into prison, condemned to death. Faust, aided by Mephistopheles, finds her there, and urges her to fly with him. Weak as she is in every sense, she refuses, and in an excess of agony and grief expires, passionately imploring pardon. Nothing can go beyond this scene in pathos and truth to nature. Ophelia alone compares with Gretchen in her last hour of trial. When the Evil One is fiendishly gloating over the consummation of the wretched catastrophe, celestial voices are suddenly heard welcoming the repentant sinner. Then Mephistopheles, startled at the unexpected turn taken in the ill-success of his subtle devices, becomes a suppliant himself, in which posture he figures as Margaret’s soul is borne by heavenly messengers to its lasting rest.

Such, in barest outline, is the story -- a story probably the most human in interest of any associated with a great opera. It emphasises -- if one is serious enough to seek for its meaning -- the eternally applicable lesson expressed in words: "No man liveth to himself, and no man dieth to himself." The whirlpool of destruction that engulfs Margaret, her babe, and her soldier brother, sets toward Faust as a centre. Through the grand tragedy runs the feeling that sensual pleasure can never satisfy the human soul. But neither -- and that again is emphasised by the lonely student Faust in his cell -- neither can selfish self-absorption and one-sided development. If a man is to fill his place rightly in the world some ideal he must have -- Love, Friendship, or Humanity. Carlyle, Goethe’s great disciple, put it all in a nutshell when he said: "Love not pleasure, love God; this is the Everlasting Yea in which whosoever walketh and worketh it is well with him." If he should walk and work otherwise, better for him, as it had been better for Faust, to drain the fatal beaker at once.

People sometimes ask if there was a real Faust, just as children ask if there was a real Blue Beard. The question is as easily answered in the one case as in the other. The Faust round whom such a wealth of halo and legend has gathered, the "black doctor" whose story assumed literary form before the sixteenth century was out, was an actual personage. He "flourished," as the saying is, about the time that Martin Luther was preaching the Reformation in Germany. Luther, indeed, spoke freely of him as an awful example of the subtlety and wickedness of the devil, and of the prudence of avoiding perilous dealings with him. He can be traced in references of contemporaries from 1507 to 1540. Melancthon, most precise of Reformers, records having conversed with him. Manlius, too, a pupil of Melancthon, tells, in a work of 1562, how Faust had "studied magic at Cracow, worked many vain wonders throughout Germany," and was at last carried off by the enemy of mankind. The doctor is said, in fact, to have entered into a compact with the Prince of Darkness, by which he undertook, in return for twenty-five years’ unrestrained enjoyment, to surrender himself entirely at the end of the term to "the party of the second part." According to the traditional tale, the contract was fulfilled with remarkable promptitude in the October of 1538, when Faust, lying at a country inn, was torn to pieces by his spirit friend during the night. His name lived on in tradition and romance until the form of the mythus was fixed for all time in the Frankfort Volksbuch of 1587. Even yet Dr. Faust and his familiar, Wagner, play a conspicuous part in the puppet-shows of Germany.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |