Music with Ease > Classical Music > Ludwig Van Beethoven

Ludwig Van Beethoven

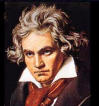

-- Beethoven

What musician, going up the Rhine, would fail to make a call at the pretty university town of Bonn, where Ludwig van Beethoven was born in the December of 1770? There, to-day, stands a memorial monument, on the pedestal of which is engraved, in all its rugged simplicity and appropriateness, the one word "BEETHOVEN." And there, too, in a side street known as the Bonngasse, one may see the identical house whose lowly walls echoed to the infant cries of this musical giant who bound the eighteenth to the nineteenth century. For many years the house was given over to common and even ignoble uses; but at last, in 1889, it was purchased (for nearly £3000) by a number of Beethoven enthusiasts, and now it is filled with relics of Beethoven interest, which every admirer of the great master loves to see.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Beethoven came of a musical family, for his grandfather was a kapellmeister, while his father, a tenor singer, filled a small musical post in the establishment of the Elector of Cologne. The grandfather was born in Antwerp, but he quarreled with his parents there, and went off to Bonn in 1732. His wife, Beethoven’s grandmother, took to drink, and Beethoven’s father did the same. The father was, in fact, a confirmed sot, loafing about the beer-houses, and boasting to his muddled companions about his boy’s gifts and his bright future. He had heard of the prodigy Mozart and the money he brought to his parents, and he conceived the idea of exploiting his own son for the same purpose.

True, his son was no prodigy: on the contrary, he early showed a positive dislike for music. Nevertheless, the father kept him slaving away at the piano, and would often give him a beating when he evinced a disinclination to practice. We read of the little fellow being dragged from bed and set down to the instrument when the drunken father would come home late at night. The parent’s conduct cast a deep gloom over Beethoven’s youth; and it can hardly be doubted that the drudgery he imposed and the misery he caused in the house formed the germs of suspicion and misanthropy which afterwards so markedly showed themselves in Beethoven’s character. The miserable toper ended his life at last by his own hand, but not before Beethoven, at the age of nineteen, had been officially appointed head of the family.

In process of time the future composer’s musical sensibilities awakened, and having been sent to the Court organist for lessons, he made such progress that before he was twelve he was deputizing for his master at the Court chapel. At thirteen he became a "cembalist" -- a pianist, as we would say -- in the are orchestra. And thereby hangs a tale. One of the singers, a man named Keller, had been boasting of his correct ear, and declaring that Beethoven could not "throw him out." A wager was ultimately accepted on the point. During an interlude in one piece, Beethoven modulated to a key so remote that, though he struck the note which Keller should have taken up, Keller was defeated, and came to a dead stand. Exasperated by the laughter of the audience, he complained of Beethoven to the Elector, who gave the cembalist "a most gracious reprimand," and told him not to play any more clever tricks of that sort.

Beethoven seems to have had no regular course of theoretical instruction in his native town; but when he was seventeen he managed to get to Vienna, where he met Mozart and had some lessons from him. "Mind, you will hear that boy talked of," said Mozart to a friend after Beethoven had played to him. Beethoven subsequently met Haydn, who first encouraged him to persevere with his studies, and then took him for a pupil. Beethoven refused to describe himself as Haydn’s pupil on the title-pages of his early works because, as he said, "I never learnt anything from him." But this was mere perversity. The truth was that he and Haydn did not pull well together. How could they? Their natures were totally different; and Beethoven, self-willed and passionate, must have been an unmanageable pupil with any master. Besides, Haydn was now an old man, and he may not have had time or inclination to attend o his pupil as the pupil thought necessary. At any rate, Beethoven left Haydn and put himself under Albrechtsberger, then organist of Vienna Cathedral, who conducted him through the "arid wastes of ingenuity," and made him write as many exercises as would have served for a generation of young composers.

In the meantime Beethoven had lost his sweet, patient mother, who died of consumption at the age of forty-one, leaving the young musician, on his return to Bonn, to manage as best he could his dissipated father and the domestic concerns of the family. Happily he made friends of several influential people, who helped him in his home struggles, and did kindly offices of various kinds for him. And Bonn soon saw him for the last time. He left it when he was twenty-two, and he never went back. There were no family ties to recall him, and the fulfilment of his manifest destiny required that he should live in Vienna.

So, then, to Vienna we go with him. There he gradually made name and fame for himself among the dilettante aristocracy, in whose houses he was a frequent and favoured guest. As a player he never showed any extraordinary facility and dexterity, but his style was arresting, and as an extemporiser he was unrivalled. When he played, his muscles swelled and his eyes rolled wildly. He "seemed like a magician overmastered by the spirit that he conjured up." He began to appear in public; and in 1796 he got as far as Berlin, where he played before the King and was treated with appreciative distinction.

So far, he had not composed much; and indeed it was not till close on thirty that he produced his first symphony, the great C major. Nearly all his earlier works were roundly abused by the critics. One spoke of a certain composition as "the confused explosions of a talented young man’s overweening conceit." Another compared the second symphony with a monster, "a dragon wounded to death and unable to die, threshing around with its tail in impotent rage." Of the seventh symphony even Weber declared that "the extravagances of this genius have reached the ne plus ultra, and Beethoven is quite ripe for the madhouse." It is really amusing to turn up some of the old newspaper notices and read them now. This, for example: "Mr. Van Beethoven goes his own path, and a dreary, eccentric, and tiresome path it is: learning, learning, and nothing but learning, but not a bit of nature or melody. And, after all, it is but a crude and undigested learning, without method or arrangement, a seeking after curious modulations, a hatred of ordinary progressions, a heaping up of difficulties, until all the pleasure and patience are lost." That was how Beethoven’s contemporaries regarded his earlier works. Then, of course, when deafness came upon him, they turned still more sarcastic. He could not hear, they said: how could he understand what horrors of sound he was evolving? When his Fidelio was first performed in 1805, they declared that never before had anything so incoherent, coarse, wild, and ear-splitting been heard; and they attributed it largely to his physical defect. They had not yet learnt, apparently, that the really great composer is always in advance of his time.

Once having got the rush, Beethoven’s musical inspiration came so profusely that he soon had several works going on at the same time, and had no little difficulty in keeping separate the several developments. His ideas poured forth like volcanic eruptions. His usual practice was to jot them down roughly, as they came into his head, in little sketch books, which were filled up in a most eccentric way -- notes scribbled down as often as not without any stave at all, and at certain distances apart, which were evidently intended as vague substitutes for lines and spaces. In his younger days he spent much time in the woods and the open country, and it was there that the "raptus" would most generally find him. "No man on earth can love the country as I do," he said. But the country was not the same to him when he could not hear the birds. Then he would stamp and stride about his room like a caged lion, singing and shouting the themes that were coursing through his brain, and thrashing them out in a wild way on the piano.

And this brings us to the great tragic fact of Beethoven’s career -- his deafness, which came upon him in 1800, after he had published the thirty-two sonatas, three concertos, two symphonies, nine trios, and numerous smaller works. In all musical biography there is nothing so terrible to read about as the deafness of Beethoven. For a musician to lose his sight is calamity enough, and several musicians besides Bach and Handel have suffered it. But the blind musician can still hear his own creations. The deaf musician may write, as Beethoven wrote, some of the grandest inspirations ever given to the world, but while others are hearing these inspirations, he cannot hear. Such was Beethoven’s painful experience. It is staggering to reflect that he never himself felt the thrill of that noble music of his own, produced in his later years.

Yet it is thus, and ever thus --

The glory is in giving;

Those monarchs taste a deathless joy

That agonised while living.

This distressing affliction of Beethoven’s life had begun to show itself as early as 1778, but it was two years later before it became acute. When he awoke to his danger, a cry of woe went forth that touched the hearts of all his friends, who, alas! with the most skillful aurists, were powerless to help.

"How miserable my future life will be," he exclaims, -- "to have to shun all that is most dear to me! Oh, how happy I should be if I had my perfect hearing; but as it is, my best years will fly away without my being able to do all that may talent and power would have bid me do. I can say that I spend a most miserable life; for two years I have been shunning all society, because I find it impossible to tell the people ‘I am deaf.’ If I were of any other profession, this deficiency would not be felt, but with my music, it is a terrible condition to be in. Add to this, my enemies -- not a few in number -- what will they say to it?"

In the theatre he had to lay his ears close to the orchestra in order to understand the actors; and the higher notes of the instruments and voices he could not hear at all when only a little distance away. "When in conversation," he says, "I often wonder that some people never get acquainted with my state, but, having much amusement, their attention is drawn away. Some sounds but no words; however, as soon a some one screams out to me -- this is unbearable." Who can gauge the mental anguish of a musician thus tortured. Read this: "He softly struck a full chord. Never will another so woefully, with such a melancholy effect, pierce my soul. With his right hand he held the chord of C major, and in the bass he struck B, looking at me and repeating -- in order to let the sweet tone if his piano fully come out-the wrong chord -- and the greatest musician in the world did not hear the dissonance!" These are the words of an eye-witness, written in the year 1825. The "greatest musician in the world" struck a wrong chord, and he had no hearing to acquaint him with the fact!

Several efforts were made by the surgeons to alleviate the malady, but while some of these gave a little temporary relief, the clouds gathered thicker and darker than ever, and in the end every ray of hope became obscured. Need we be surprised that Beethoven took to debating with himself whether life was really worth living? He did indeed discuss the question seriously in his own mind, and it was only after a keen struggle that virtue and art prevailed. "I will meet my fate fearlessly, and it shall not wholly overwhelm me," he said. It was about this time that he wrote that pitiful letter to his brothers which was to be opened only after his death. It begins: "Oh, ye who think or declare me to be hostile, morose, and misanthropical, how unjust you are, and how little you know the secret cause of what appears to you! My heart and mind were ever from childhood prone to the most tender feelings of affection, and I was always disposed to accomplish something great. But you must remember that six years ago I was attacked by an incurable malady, aggravated by unskillful physicians, deluded from year to year, too, by the hope of relief, and at length forced to the conviction of a lasting affliction."

Proceeding to detail, he says: "Alas! how could I proclaim the deficiency of a sense which ought to have been more perfect with me than with other men? Alas! I cannot do this. Forgive me, therefore, when you see me withdraw from you with whom I would so gladly mingle. Completely isolated, I only enter society when compelled to do so. I must live like an exile." In the country he was thrown into the deepest melancholy. "What humiliation when any one beside me heard a flute in the far distance, and I heard nothing; or when others heard a shepherd singing, and I heard nothing. Such things brought me to the verge of desperation, and well-nigh caused me to put an end to my life. Art, art alone deterred me." Was there ever such a wail of despair? "I joyfully hasten to meet death," he writes at another time. "If death come before I have had the opportunity of developing my artistic powers, then, notwithstanding my cruel fate, he will come too early for me, and I should wish for him at a more distant period. But even then I shall be content, for his advent will release me from a state of endless suffering."

In that birth-house museum at Bonn we have the most melancholy signs of Beethoven’s deafness. There are ear-trumpets and the pianoforte by whose help he strove so long and so hopeless to remain in communion with the world of sound. The piano was made specially for him, with extra strings. So long as he could hear a tone, Beethoven used this instruments. Then Maelzel, the metronome man, who invented and made the ear-trumpets for him, built a resonator for the piano. It was fixed on the instrument so that it covered a portion of the sounding-board and projected over the keys. "Seated before the piano, his head all but inside the wooden shell, one of the ear-trumpets held in place by an encircling brass band, Beethoven would pound upon the keys till the strings jangled discordantly with the violence of the percussion, or flew asunder with shrieks as of mortal despair." Though the ear-trumpets had been useless for five years, they were kept in Beethoven’s study till his death. Then they found their way into the Royal Library at Berlin, where they remained until Emperor William II. presented them to the Bonn collection.

The deafness affected Beethoven in other than professional affairs. Directly or indirectly, it prevented him marrying, as he had wished to do. As a young man he had been very sensible to the charms of female society. Ladies would knit him comforters and make him light puddings, and he would even condescend to lie on their sofas after dinner while they played his sonatas. His early friend Wegeler says that he was never without a love affair; and these affairs took, in more than one case, the serious form of an offer of marriage. But no bride was Beethoven destined to bring to the altar. Writing to his pupil Ries in 1816 he says: "May best wishes to your wife. Unfortunately I have none. I found One only, and her I have no chance of ever calling mine." The "one only" was most likely the "immortal beloved" of the passionate letters found in the composer’s desk after his death -- the beautiful Giulietta, Countess Guicciardi, to whom the so-called "Moonlight" sonata is dedicated. The Countess married a Count Gallenberg, and Beethoven said of the marriage: "Heaven forgive her, for she did not know what she was doing!" He wrote further: "I was much loved by her -- far better than she ever loved her husband." But Beethoven was poor, in bad health, and -- deaf; and marriage in his case was out of the question. One does not fancy that he would commend himself as a possible husband. A man who afterwards threw books and even chairs at the head of a stupid, dishonest servant, was a trifle too tempestuous for a domestic companion. And, indeed, he came to realise this himself, for he said he was "excessively glad that not one of the girls had become his wife, whom he had passionately loved in former days, and thought at the time it would be the highest joy on earth to possess." Alas! poor Beethoven.

And this may serve us as a suggestion for introducing some details of Beethoven’s character as a man, and of his general relations towards life and his fellows. On his younger years he was rather particular about his appearance. Before he left Bonn, we find him wearing a sea-green dress coat, green short-clothes with buckles, silk stocking, white flowered waistcoat with gold lace, white cravat, frizzed hair tied in a queue behind, and a sword. When he went first to Vienna he dressed in the height of fashion, sported a seal ring, and carried a double eyeglass. Later, he became extremely negligent about his person. An artist who painted his portrait in 1815 described him as wearing a pale-blue dress coat with yellow buttons, white waistcoat and necktie, but his whole aspect bespeaking disorder. Even if he did dress neatly, nothing could prevent him removing his coat if it were warm, not even in the presence of princes or ladies. Geniuses are generally Bohemian, often outré. Beethoven was no exception. He began by disdaining to have his hair cut. He wanted a servant, and one applicant mentioned the accomplishment of hair-dressing. "It is no object to me to have my hair dressed," growled Beethoven. Remembering the characteristic portraits, one agrees with him. Fancy a portrait of Beethoven with those fine Jupiter Olympus locks reduced to order!

But it was not his hair only that he refrained from dressing: he hardly, even, as we would say, dressed himself. When Czerny first saw him in his rooms, he found him clad in a loose, hairy, stuff, which made him rather more like Robinson Crusoe than the leading musician in Europe. His ears were filled with wool, which he had soaked in some yellow substance; his beard showed more than half an inch of growth; and his hair stood up in a thick shock that betokened an unacquaintance with comb and brush for many a day. Moscheles tells that he could not be made to understand clearly why he should not stand in his night-shirt at the open window; and when he attracted a crowd of juveniles by this eccentricity, he inquired with perfect simplicity "what those confounded boys were hooting at."

He seems to have been rather fond of the open window, for he generally shaved there. He "cut himself horribly," according to one biographer, and doing it at the window he enabled the people in the street to share in the diversion. He had none of the graces of deportment which we expect from the modern artist. It was dangerous for him to touch anything fragile, for he was sure to break it. More than once, in a fit of passion, he flung his inkstand among the wires of the piano. He had a habit, when composing, of pouring cold water over his hands, and the people below him often suffered from a miniature flood in consequence. When he first arrived in Vienna he took dancing lessons, but, curiously enough in a musician, could never dance in time. He was absent-minded to the point of insanity. Whether he dined or not was immaterial to him, and there is one authentic instance of his having urged on the waiter payment for a meal which he had neither ordered nor eaten. Somebody once presented him with a horse, but he forgot all about the animal, and had its existence recalled to him only when the bill for its keep was sent in. At one time he forgot his own name and the date of his birth! A friend, not having seen him for days, asked if he had been ill. "No," he said, "but my boots have, and as I have only one pair, I was condemned to house arrest." As a matter of fact he had a pair for every day of the week, though he forgot all about that too.

He was in perpetual trouble about his rooms and his servants. He would flit on the merest pretext, and usually it was himself who was in fault. He had no patience with any sort of conventional etiquette; and thus it often happened that he would prefer the discomforts of a bachelor’s apartments to the free and luxurious housing offered him by more than one noble family. Baron Pronay prevailed upon him one summer to stay with him at Hetzendorf. But the Baron persisted in raising his hat to him whenever they met, and Beethoven was so annoyed by this that he took up his lodgings with a poor clockmaker near by. He seems to have been specially opposed to this act of courtesy. Once when he was walking along the street, he met a group of society notables, among whom he observed a particular friend of his own; but the revulsion against empty formalities was so strong in him that he kept hat tight on his head and passed by on the other side.

Every lodging turned out worse than its predecessor. Either the chimneys smoked, or the rain came through the roof, or the chairs were rickety, or the doors creaked on their hinges, or something else interfered with the comfort of the occupant. And then the servants-oh, the servants! But really Beethoven was over-exacting here. Nancy might indeed be "too uneducated for a housekeeper," but surely the fact of her telling a lie did not imply, as Beethoven said it implied, that she could not make good soup. "The cook’s off again," he tells one of his correspondents, who could hardly be surprised at the news when he learned that Beethoven had punished the cook for the staleness of the eggs by throwing the whole batch, one by one, at her head. This habit of throwing the dishes at the heads of domestics who displeased him had its comic aspect for the onlookers, but it cannot have been pleasant for the domestic. And the waiters suffered too. On one occasion when he was dining at a restaurant the waiter brought him a wrong dish. Beethoven has no sooner uttered some words of reproof (to which the offender retorted in no very polite fashion) than he took the dish of stewed beef and gravy and discharged it at the waiter’s head. The poor man was heavily loaded with plates full of different viands, so that he could not move his arms. The gravy meanwhile trickled down his face. Both he and Beethoven swore and shouted, while the rest of the party roared with laughter. At last Beethoven himself joined in the merriment at the sight of the waiter, who was hindered from uttering any more invectives by the streams of gravy that found their way into his mouth.

It was probably after the cook went "off again" that Beethoven determined to try cooking for himself. Early in the morning he went off to the market, and the astonished neighbours saw him return home with a loaf of bread and piece of meat, while greens and other vegetables peeped out of the pockets of his overcoat. Now for a time he left off playing and writing music, and devoted himself to the study of a popular cookery book. One day, when he thought himself sufficiently advanced in his new studies, he took it into his head to invite his best friends to a dinner prepared by himself. Everybody was naturally curious as to the result, and the guests were punctual to the minute. They found Beethoven busy in the kitchen with a nightcap on his head and a white apron before him.

After considerable waiting, they at length sat down to table. The composer himself was the waiter, but it is impossible to picture the dismay of the visitors and the horrors of that meal. A soup not unlike the famous black porridge of the Spartan, in which floated some shapeless and nondescript substances, a piece of boiled beef as tough as shoe-leather, half-cooked vegetables, a roast joint burnt to a cinder, and pudding like a lump of soapstone swimming in train oil -- such was the Beethoven dinner. The guests were unable to swallow a morsel. Beethoven alone ate with a keen appetite, praised every dish, and declared that the whole thing was a gigantic success. When they got into the street two hours afterwards with empty stomach, his friends gave vent to their hilarity, and never, we may be sure, did they forget that Beethoven dinner.

The composer’s behaviour to his pupils, even to ladies, was often atrocious. He would sometimes tear the music in shreds, and scatter it on the floor, or even smash the furniture. Once when an aristocratic pupil struck a wrong note he fled into the street without taking his hat from the hall. If he did consent to play in company he must have perfect silence and attention. On one occasion when this was denied him, he rose from the keyboard declaring that he would no longer play for "such hogs." He called Prince Lobkowitz an ass, and he called Hummel a "false dog." In Mme. Ertman’s drawing-room he took up the snuffers and used it as a tooth-pick.

As a conductor he was little more use than to raise a laugh. We read that "now he would vehemently spread out his arms; then when he wanted to indicate soft passages, he would bend down lower and lower until he disappeared from sight. Then as the music grew louder he would emerge, and at the fortissimo he would spring up into the air." One time when playing a concerto he forgot himself, jumped from his seat, and began to conduct. At the very outset he knocked the two candles from the piano. The audience roared. Beethoven, quite beside himself, began the piece again. The director now stationed a boy on each side of the piano to hold the candles. The same scene was reenacted. One of the boys dodged the outstretched arm; the other, interested in the music, did not notice, and received the full blow in the face, falling in a heap, candle and all! "The audience," says Siegfried, who conducted, "broke out into a truly bacchanal howl of delight, and Beethoven was so enraged that when he started again, he smashed half a dozen strings at a single chord." Such was this Colossus of music when he lost his temper.

But he had a sense of humour, too, and now and again would indulge in the most boyish of horse-play and practical jokes. He could even make fun of his troubles with servants. Writing to Holz a note of invitation to dinner, he says: "Friday is the only day on which the old witch, who certainly would have burned two hundred years ago, can cook decently, because on that day the devil has no power over her." In one letter he has a sly dig at the Vienna musicians when he tells of having made a certain set of variations "rather difficult to play" that he may "puzzle some of the pianoforte teachers here," who, he feels sure, will occasionally be asked to play the said variations! He was often sarcastic to brother artists of a lesser order. One day he found himself in the company of Himmel, when he asked Himmel to extemporize on the piano. After Himmel had played for some time, Beethoven suddenly exclaimed: "Well, when are you going to begin in good earnest?" Himmel, who had no mean opinion of his own powers, naturally started up in a rage; but Beethoven only added to his offence by remarking to those present: "I thought Himmel had just been preluding." In revenge for his insult, Himmel shortly after played Beethoven a trick. Beethoven was always eager to have the latest news from Berlin, and Himmel took advantage of this curiosity to write to him: "The latest piece of news is the invention of a lantern for the blind." Beethoven was completely taken in by the childish joke, repeated it to his acquaintances, and wrote to Himmel to demand full particulars of the remarkable invention. The answer received was such as to bring both the correspondence and the friendship to a close. Beethoven never enjoyed a joke at his own expense.

In this respect he did not always do to others as he would have others do to him. A certain lady admirer was very anxious to have a lock of Beethoven’s hair. A common friend undertook to approach the master on the subject, and the result was that Beethoven sent a tuft of hair cut from a goat’s beard! The lady was overjoyed at possessing her treasure, but, unfortunately, the secret soon leaked out. Her husband wrote a letter of expostulation to Beethoven, who, conscious of his offence, at once cut off a lock of his own hair, and enclosed it in a note in which he asked the lady’s forgiveness for what had occurred. Even when he was dying his sense of humour did not forsake him. When he had to be "tapped," he remarked to the doctor: "Better water from the body than from the body than from the pen." Two days before his death, Schindler, one of his biographers, who was then with him, wrote to a friend: "He feels that his end is near, for yesterday he said to Breuning and me: ‘Clap your hands, friends; the play is over.’ He advances towards death with really Socratic wisdom and exampled equanimity."

And what a weary, tragic advance it had been, all these years! From the time of his deafness onwards, he was constantly adding to the world’s stores of the highest and best in music, and the legacy we now enjoy as the result of his genius is the most universal gift of music that has ever come from human hand and human head. The years, as they passed, brought nothing very eventful; and in December 1826 Beethoven found himself on a sick-bed, in great poverty, and unable to compose a single line. On the afternoon of March 26, 1827, he was seized with his last mortal faintness. "Thick clouds were hanging about the sky; outside, the snow lay on the ground; towards evening the wind rose; at nightfall a terrific thunder storm burst over Vienna, and whilst the storm was still raging, the spirit of the sublime master departed." He died in his fifty-seventh year, and was buried in the cemetery of Wahring, near Vienna.

It was generally felt that a man of the most powerful character and of unique genius had been lost to the world. And yet, to the public of that day, his music was not a tithe of what it is to us now. Nay, we can say more than that, for Beethoven is one of the few creators of art whom one, ever so blessed with musical intelligence, may study for a lifetime and never exhaust. Beethoven speaks a language no composer before him had spoken, and treats of things no one had dreamt of before. Yet it seems as if he were speaking of matters long familiar in one’s mother tongue -- as though he touched upon emotions one had lived through in some former existence. The warmth and depth of his ethical sentiment is now felt all the world over, and it will ere long be universally recognised that he has leaved and widened the sphere of human emotions in a manner akin to that in which the conceptions of great philosophers and poets have widened the sphere of men’s intellectual activity.

Beethoven might be described as the Carlyle of music. Wagner said of him that he faced the world with a defiant temperament, and kept an almost savage independence. Like Carlyle, he detested sham, and humbug, and conventionality above all things. He believed that "a man’s man for a’ that" whether he be prince or plebeian, so that he be honest, and true, and good. There is a capital story of him in connection with the visit of a bumptious, ignorant brother who had amassed a fortune and purchased a fine estate. The brother had called when Beethoven was from home, and had left a card inscribed "Johann van Beethoven, Land Proprietor." This enraged the composer, who simply wrote on the other side, "Ludwig van Beethoven, Brain Proprietor," and returned the card without comment.

Of Beethoven’s personal, appearance we have several descriptions. Thayer, his leading biographer, says he was small and insignificant-looking, dark-complexioned, pock-marked, black-eyes, and black-haired. The hair was luxuriant, and when he walked in the wind it gave him "a truly Ossianic and demoniac appearance." His fingers were short and nearly all of the same length. One lady said his forehead was "heavenly." Another once pointed to it and exclaimed: "How beautiful, how noble, how spiritual that brow!" Beethoven was silent for a moment and then said: "Well, then, kiss this brow." Which she did. But perhaps the best description is that of Sir Julius Benedict, who met Beethoven in 1823. Sir Julius writes: "Who could ever forget those striking features? The lofty vaulted forehead, with thick grey and white hair encircling it in the most picturesque disorder; that square lion’s nose, that broad chin, that noble and soft mouth. Over the cheeks, seamed with scars from the smallbox, was spread high colour. From under the bushy, closely compressed eyebrows flashed a pair of piercing eyes. His thick-set Cyclopean figures told of a powerful frame."

But who does not know that rugged-looking figure, which reminded Weber of King Lear? Truly a noble face, with "a certain severe integrity and passionate power and lofty sadness about it, seeming in its elevation and wideness of expression to claim kindred with a world of ideas out of all proportion to our own." In the world’s portraiture of great men there is nothing exactly like it.

Reader Feedback

Our thanks to Bob Rodes, a visitor to our website, who sent in the following comments and corrections regarding the above article.

(1) In your Beethoven biography, the following quote is incorrect:

"...the great tragic fact of Beethoven's career -- his deafness, which came upon him in 1800, after he had published the thirty-two sonatas..."

In fact, Beethoven had published only the first ten of his sonatas by 1800.

(2) Also, the identity of Countess Guicciardi as the "immortal beloved" has been fairly convincingly challenged, notably in Maynard Solomon's excellent biography of Beethoven. I tend to accept Solomon's point of view that it was a letter to one Countess Antonie Brentano, upon her expressing a willingness to divorce her husband in order to marry Beethoven. It's basically a "Dear Jane" letter: flagrant idealist that he was, he would have backed out of any real relationship.

Whether this is true or not, I would at least revise the text to say something like the "immortal beloved" was "thought to be" the Countess Guicciardi, rather than that she simply was.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |