Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > Parsifal (Wagner) - Synopsis

Parsifal - Synopsis

An Opera by Richard Wagner

At the Bayreuth performances there were alternating casts. Winckelmann was the Parsifal of the première, Gudehus to the second performance, Jäger of the third. The alternating Kundrys were Materna, Marianne Brandt, and Malten; Gurnemanz Scaria and Siehr; Amfortas Reichmann; Klingsor, Hill and Fuchs. Hermann Levi conducted.

In the New York cast Ternina was Kundry, Burgstaller Parsifal, Van Rooy Amfortas, Blass Gurnemanz, Gortiz Klingsor, Journet Titurel, Miss Moran and Miss Braendle the first and second, Harden and Bayer the third and fourth Esquires, Bayer and Muhlmann two Knights of the Grail, Homer a Voice.

CHARACTERS

AMFORTAS, son of TITUREL, ruler of the Kingdom of the Grail…. Baritone-Bass

TITUREL, former ruler……………………………………………….. Bass

GURNEMANZ, a veteran Knight of the Grail……………………….. Bass

KLINGSOR, a magician………………………………………………. Bass

PARSIFAL……………………………………………………………. Tenor

KUNDRY…………………………………………………………….. Soprano

FIRST AND SECOND KNIGHTS………………………………….. Tenor-Bass

FOUR ESQUIRES………………………………………………….. Sopranos & Tenors

SIX OF KLINGSOR’S FLOWER MAIDENS……………………… Sopranos

Brotherhood of the Knights of the Grail; Youths and Boys; Flower Maidens (two choruses of sopranos and altos).

Soprano Amalie Materna as Kundry in Wagner's opera, Parsifal, at Bayreuth in 1882.

Time: The Middle Ages.

Place: Spain, near and in the castle of the Holy Grail; in Klingsor’s enchanted castle and in the garden of castle.

"Parsifal" is a familiar name to those who have heard "Lohengrin." Lohengrin, it will be remembered, tells Elsa that he is Parsifal’s son and one of the knights of the Holy Grail. The name is written Percival in "Lohengrin," as well as in Tennyson’s "Idyls of the King." Now, however, Wagner returns to the quainter and more "Teutonic" form of spelling. "Parsifal" deals with an earlier period in the history of the Grail knighthood than "Lohengrin." But there is a resemblance between the Grail music in "Parsifal" and the "Lohengrin" music -- a resemblance not in melody, nor even in outline, but merely in the purity and spirituality that breathes through both.

Three legends supplied Wagner with the principal characters in this music-drama. They were "Percival le Galois; or Contes de Grail," by Chretien de Troyes (1190); "Parsifal," by Wolfram von Eschenbach, and a manuscript of the fourteenth century called by scholars the "Mabinogion." As usual, Wagner has not held himself strictly to any one of these, but has combined them all, and revivified them through the alchemy of his own genius.

Into the keeping of Titurel and his band of Christian knights has been given the Holy Grail, the vessel from which the Saviour drank when He instituted the Last Supper. Into their hands, too, has been placed, as a weapon if defence against the ungodly, the sacred Spear, the arm with which the Roman soldier wounded the Saviour’s side. The better to guard these sanctified relics Titurel, as King of the Grail knighthood, has reared a castle, Montsalvat, which from its forest-clad height, facing Arabian Spain, forms a bulwark of Christendom against the pagan world and especially against Klingsor, a sorcerer and an enemy of the good. Yet time and again this Klingsor, whose stronghold is near-by, has succeeded in enticing champions of the Grail into his magic garden, with its lure of flower-maidens and its arch-enchantress Kundry, a rarely beautiful woman, and in making them his servitors against their one-time brothers-in-arms.

Even Amfortas Titurel’s son, to whom Titurel, grown old in service and honour, has confided his reign and wardship, has not escaped the thrall of Klingsor’s sorcery. Eager to begin his reign by destroying Klingsor’s power at one stroke, he penetrated into the garden to attack and slay him. But he failed to reckon with human frailty. Yielding to the snare so skillfully laid by the sorcerer and forgetting, at the feet of the enchantress, Kundry, the mission upon which he had sallied forth, he allowed the sacred Spear to drop from his hand. It was seized by the evil-doer he had come to destroy, and he himself was grievously wounded with it before the knights who rushed to his rescue could bear him off.

This wound no skill has sufficed to heal. It is sapping Amforta’s strength. Indecision, gloom, have come over the once valiant brotherhood. Only the touch of the sacred Spear that made the wound will avail to close it, but there is only one who can regain it from Klingsor. For to Amfortas, prostrate in supplication for a sign, a mystic voice from the sanctuary of the Grail replied:

By pity guided,

The guileless fool;

Wait for him,

My chosen tool.

This prophecy the knights construe to signify that their king’s salvation can be wrought only by youth so "guileless," so wholly ignorant of sin, that, instead of succumbing to the temptations of Klingsor’s magic garden, he will become, through resisting them, cognizant of Amfortas’s guilt, and stirred by pity for him, make his redemption the mission of his life, regain the Spear and heal him with it. And so the Grail warders are waiting, waiting for the coming of the "guileless fool."

The working out of this prophecy forms the absorbing subject of the story of "Parsifal." The plot is allegorical. Parsifal is the personification of Christianity, Klingsor of Paganism, and the triumph of Parsifal over Klingsor is the triumph of Christianity over Paganism.

The character of Kundry is one of Wagner’s most striking creations. She is a sort of female Ahasuerus -- a wandering Jewess. In the Mabinogion manuscript she is no other than Herodias, condemned to wander for ever because she laughed at the head of John the Baptist. Here Wagner makes another change. According to him she is condemned for laughing in the face of the Saviour as he was bearing the cross. She seeks forgiveness by serving the Grail knights as messenger on her swift horse, but ever and anon she is driven by the curse hanging over her back to Klingsor, who changes her to a beautiful woman and places her in his garden to lure the Knights of the Grail. She can be freed only by one who resists her temptations. Finally she is freed by Parsifal and is baptized. In her character of Grail messenger she has much in common with the wild messengers of Walhalla, the Valkyrs. Indeed, in the Edda Saga, her name appears in the first part of the compound Gundryggja, which denotes the office of the Valkyrs.

The Vorspeil (Preface)

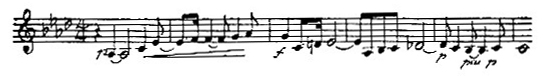

The Vorspiel to "Parsifal" is based on three of the most deeply religious motives in the entire work. It opens with the Motive of the Sacrament, over which, when it is repeated, arpeggios hover, as in the religious paintings of old masters angel forms float above the figure of virgin or saint.

Through this motive we gain insight into the office of the Knights of the Grail, who from time to time strengthen themselves for their spiritual duties by partaking of the communion, on which occasions the Grail itself is uncovered. This motive leads to the Grail Motive, effectively swelling to forte and then dying away in ethereal harmonies, like the soft light with which the Grail illumines the hall in which the knights gather to worship.

The trumpets then announce the Motive of Faith, severe but sturdy -- portraying superbly the immutability of faith.

The Grail Motive is heard again and then the Motive of Faith is repeated, its severity exquisitely softened, so that it conveys a sense of peace which "passeth all understanding."

The rest of the Vorspiel is agitated. That portion of the Motive of the Sacrament which appears later as the Spear Motive here assumes through a slight change a deeply sad character, and becomes typical throughout the work of the sorrow wrought by Amfortas’s crime. I call it the Elegiac Motive.

Thus the Vorspiel depicts both the religious duties which play to prominent a part in the drama, and unhappiness which Amfortas’s sinful forgetfulness of these duties has brought upon himself and his knights.

Act I. One of the sturdiest of the knights, the aged Gurnemanz, grey of head and beard, watches near the outskirts of the forest. One dawn finds him seated under a majestic tree. Two young Esquires lie in slumber at his feet. Far off, from the direction of the castle, sounds a solemn reveille.

"Hey! Ho!" Gurnemanz calls with brusque humour to the Esquires. "Not forest, but sleep warders I deem you!" The youths leap to their feet; then, hearing the solemn reveille, kneel in prayer. The Motive of Peace echoes their devotional thoughts. A wondrous peace seems to rest upon the scene. But the transgression of the King ever breaks the tranquil spell. For soon two Knights come in the van of the train that thus early bears the King from a bed of suffering to the forest lake near-by, in whose waters he would bathe his wound. They pause to parley with Gurnemanz, but are interrupted by outcries from the youths and sounds of rushing through air.

"Mark the wild horsewoman!" -- "The mane of the devil’s mare flies madly!" -- "Aye, ‘tis Kundry!" -- "She has swung herself off," cry the Esquires as they watch the approach of the strange creature that now rushes in -- a woman clad in coarse, wild garb girdled high with a snakeskin, her thick black hair tumbling about her shoulders, her features swarthy, her dark eyes now flashing, now fixed and glassy. Precipitately she thrusts a small crystal flask into Gurnemanz’s hand.

"Balsam -- for the king!" There is a savagery in her manner that seems designed to ward off thanks, when Gurnemanz asks her whence she has brought the flask, and she replies: "From farther away than your thought can travel. If it fail, Arabia bears naught else that can ease his pain. Ask no further. I am weary."

Throwing herself upon the ground and resting her face on her hands, she watches the King borne in, replies to his thanks for the balsam with a wild, mocking laugh, and follows him with her eyes as they bear on his litter toward the lake, while Gurnamanz and four Esquires remain behind.

Kundry’s rapid approach on her wild horse is accompanied by a furious gallop in the orchestra. Then as she

rushes upon the stage, the Kundry Motive -- a headlong descent of the string instruments through four octaves -- is heard.

Kundry’s action in seeking balsam for the King’s wound gives us insight into the two contradictory natures represented by her character. For here is the woman who has brought all his suffering upon Amfortas striving to ease it when she is free from the evil sway of Klingsor. She is at times the faithful messenger of the Grail; at times the evil genius of its defenders.

When Amfortas is borne in upon a litter there is heard the Motive of Amfortas’s Suffering, expressive of his physical and mental agony. It has a peculiar heavy, dragging rhythm, as if his wound slowly were sapping his life.

A beautiful idyl is played by the orchestra when he knights bear Amfortas to the forest lake.

One of the youths, who has remained with Gurnemanz, noting that Kundry still lies where she had flung herself upon the ground, calls out scornfully, "Why do you lie there like a savage beast?"

"Are not even the beasts here sacred?" she retorts, but harshly, and not as if pleading for sufferance. The other Esquires would have joined in harassing her had not Gurnemanz stayed them.

"Never has she done you harm. She serves the Grail and only when she remains long away, none knows in what distant lands, does harm come to us." Then, turning to where she lies, he asks: "Where were you wandering when our leader lost the sacred Spear? Why were you not here to help us then?"

"I never help!" is her sullen retort, although a tremor, as if caused by a pang of bitter reproach, passes over her frame.

"If she wants to serve the Grail, why not send her to recover the sacred Spear!" exclaims one of the esquires sarcastically; and the youths doubtless would have resumed their nagging of Kundry, had not mention of the holy weapon caused Gurnemanz to give voice to memories of the events that have led to its capture by Klingsor. Then, yielding to the pressing of the youths who gather at his feet beneath the tree, he tells them of Klingsor -- how the sorcerer has sued for admission to the Grail brotherhood, which was denied him by Titurel, how in revenge he has sought its destruction and now, through possession of the sacred Spear, hopes to compass it.

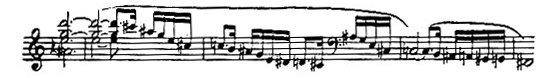

Prominent with other motives already heard, is a new one, the Klingsor Motive:

During this recital Kundry still lies upon the ground, a sullen, forbidding looking creature. At the point when Gurnemanz tells of the sorcerer’s magic garden and of the enchantress who has lured Amfortas to his downfall, she turns in quick, angry unrest, as if she would away, but is held to the spot by some dark and compelling power. There is indeed something strange and contradictory in this wild creature, who serves the Grail by ranging distant lands in search if balsam for the King’s wound, yet abruptly, vindictively almost, repels proffered thanks, and is a sullen and unwilling listener to Gurnemanz’s narrative. Furthermore, as Gurnemanz queried, where does she linger during those long absences, when harm has come to the warders of the Grail and now to their King? The Knights of the Grail do not know it, but it is none other than she who, changed by Klingsor into an enchantress, lures them into his magic garden.

Gurnemanz concludes by telling the Esquire that while Amfortas was praying for a sign as to who could heal him, phantom lips pronounced these words:

By pity lightened

The guileless fool;

Wait for him,

My chosen tool.

This introduces an important motive, that of the Prophecy, a phrase of simple beauty, as befits the significance of the words to which it is sung. Gurnemanz sings the entire motive and then the Esquires take it up.

They have sung only the first two lines when suddenly their prayerful voices are interrupted by shouts of dismay from the direction of the lake. A moment later a wounded swan, one of the sacred birds of the Grail brotherhood, flutters over the stage and falls dead near Gurnemanz. The knights follow in consternation. Two of them bring Parsifal, whom they have seized and accuse of murdering the sacred bird. As he appears the magnificent Parsifal Motive rings out on the horns:

It is a buoyant and joyous motive, full of the wild spirit and freedom of this child of nature, who knows nothing of the Grail and its brotherhood or the sacredness of the swan, and freely boasts of his skilful marksmanship. During this episode the Swan Motive from "Lohengrin" is effectively introduced. Then follows Gurnemanz’s noble reproof, sung to a broad expressive melody. Even the animals are sacred in the region of the Grail and are protected from harm. Parsifal’s gradual awakening to a sense of wrong is one of the most touching scenes of the music-drama. His childlike grief when he becomes conscious of the pain he has caused is so simple and pathetic that one cannot but be deeply affected.

After Gurnemanz has ascertained that Parsifal knows nothing of the wrong he committed in killing the swan he plies him with questions concerning his parentage. Parsifal is now gentle and tranquil. He tells or growing up in the woods, of running away from his mother to follow a cavalcade of knights who passed along the edge of the forest and of never having seen her since. In vain he endeavours to recall the many pet names she gave him. These memories of his early days introduce the sad motive of his mother, Herzeleid (Heart’s Sorrow) who has died in grief.

The old knight then proceeds to ply Parsifal with questions regarding his parentage, name and native land. "I do not know," is the youth’s invariable answer. His ignorance, coupled, however, with his naïve nobility of bearing and the fact that he has made his way to the Grail domain, engender in Gurnemanz the hope that here at last is the "guileless fool" for whom prayerfully they have been waiting, and the King, having been borne from the lake toward the castle where the holy rite of unveiling the Grail is to be celebrated that day, thither Gurnemanz in kindly accents bids the youth follow him.

Then occurs a dramatically effective change of scene. The scenery becomes a panorama drawn off toward the right, and as Parsifal and Gurnemanz face toward the left they appear to be walking in that direction. The forest disappears; a cave opens in rocky cliffs and conceals the two; they are then seen again in sloping passages which they appear to ascend. Long sustained trombone notes softly swell; approaching peals of bells are heard. At last they arrive at a mighty hall which loses itself overhead in a high vaulted dome, down from which alone the light streams in.

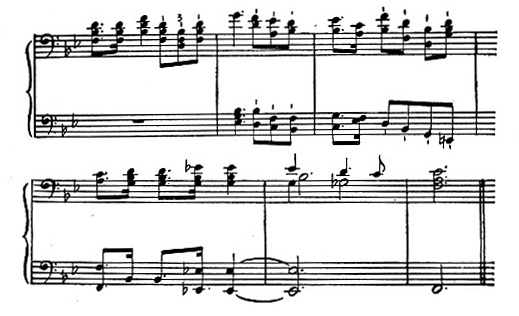

The change of scene is ushered in by the solemn Bell Motive, which is the basis of the powerful orchestral interlude accompanying the panorama, and also the scene in the hall of the Grail Castle.

As the communion, which is soon to be celebrated, is broken in upon by the violent grief and contrition of Amfortas, so, the majestic sweep of this symphony is interrupted by the agonized Motive of Contrition, which graphically portrays the spiritual suffering of the King.

This subtly suggests the Elegiac Motive and the Motive of Amfortas’s Suffering, but in greatly intensified degrees. For it is like an outcry of torture that effects both body and soul.

With the Motive of the Sacrament resounding solemnly upon the trombones, followed by the Bell Motive, sonorous and powerful, Gurnemanz and Parsifal enter the hall, the old knight giving the youth a position from which he can observe the proceedings. From the deep colonnades on either side in the rear the knights issue, march with stately tread, and arrange themselves at the horseshoe-shaped table, which incloses a raised couch. Then, while the orchestra plays a solemn processional based on the Bell Motive, they intone the chorus: "To the last love feast." After the first verse a line of pages crosses the stage and ascend into the dome. The graceful interlude here is based on the Bell Motive.

The chorus of knights closes with a glorious outburst of the Grail Motives as Amfortas is borne in, preceded by pages who bear the covered Grail. The King is lifted upon the couch and the holy vessel is placed upon the stone table in front of it. When the Grail Motive has died away amid the pealing of the bells, the youths in the gallery below the dome sing a chorus of penitence based upon the Motive of Contrition. Then the Motive of Faith floats down from the dome as an unaccompanied chorus for boys’ voices -- a passage of ethereal beauty -- the orchestra whispering a brief postludium like a faint echo. This is, when sung as it was at Bayreuth, where I heard the first performance of "Parsifal" in 1882, the most exquisite effect of the whole score. For spirituality it is unsurpassed. It is an absolutely perfect example of religious music -- a beautiful melody without the slightest worldly taint.

Titurel now summons Amfortas to perform his sacred office -- to uncover the Grail. At first, tortured by contrition for his sin, of which the agony from his wound is a constant reminder, he refuses to obey his aged father’s summons. In anguish he cries out that he is unworthy of the sacred office. But again ethereal voices float down from the dome. They now chant the prophecy of the "guileless fool" and, as if comforted by the hope of ultimate redemption, Amfortas uncovers the Grail. Dusk seems to spread over the hall. Then a ray of brilliant light darts down upon the sacred vessel, which shines with a soft purple radiance that diffuses itself through the hall. All are on their knees save the youth, who has stood motionless and obtuse to the significance of all he has heard and seen save that during Amfortas’s anguish he has clutched his heart as if he too felt the pang. But when the rite is over -- when the knights have partaken of communion -- and the glow has faded, and the King, followed by his knights, has been borne out, the youth remains behind, vigorous, handsome, but to all appearances a dolt.

"Do you know what you have witnessed?" Gurnemanz asks harshly, for he is grievously disappointed.

For answer the youth shakes his head.

"Just a fool, after all," exclaims the old knight, as he opens a side door to the hall. "Begone, but take my advice. In future leave our swans alone, and seek yourself, gander, a goose!" And with these harsh words he pushes the youth out and angrily slams the door behind him.

This jarring break upon the religious feeling awakened by the scene would be a rude ending for the act, but Wagner, with exquisite tact, allows the voices in the dome to be heard once more, and so the curtains close, amid the spiritual harmonies of the Prophecy of the Guileless Fool and of the Grail Motive.

Act II. This act plays in Klingsor’s magic castle and garden. The Vorspiel opens with the threatful Klingsor motive, which is followed by the Magic and Contrition Motives, the wild Kundry Motive leading over to the first scene.

In the inner keep of his tower, stone steps leading up to the battlemented parapet and down into a deep pit at the back, stands Klingsor, looking into a metal mirror, whose surface, through his necromancy, reflects all that transpires within the environs of the fastness from which he ever threatens the warders of the Grail. Of all that just has happened the warders of the Grail. Of all that just has happened in the Grail’s domain it has made him aware; and he knows that of which Gurnemanz is ignorant -- that the youth, whose approach the mirror divulges, once in his power, vain will be prophecy of the "guileless fool" and his own triumph assured. For it is that same guileless fool" the old knight impatiently has thrust out.

Klingsor turns toward the pit and imperiously waves his hand. A bluish vapour rises from the abyss and in it floats the form of a beauteous woman -- Kundry, not the Kundry of a few hours before, disheveled and in coarse garb girdled with snake-skin; but a houri, her dark hair smooth and lustrous, her robe soft, rich Oriental draperies. Yet even as she floats she strives as though she would descend to where she has come from. While the sorcerer’s harsh laugh greets her vain efforts. This then is the secret of her strange actions and her long disappearances from the Grail domain, during which so many of its warders have fallen into Klingsor’s power! She is the snare he sets, she the arch-enchantress of his magic garden. Striving as he hints while he mocks her impotence, to expiate some sin committed by her during a previous existence in the dim past, by serving the brotherhood of the Grail knights, the sorcerer’s power over her is such that at any moment he can summon her to aid him in their destruction.

Well she knows what the present summons means. Approaching the tower at this very moment is the youth whom she has seen in the Grail forest, and in whom she, like Klingsor, has recognized the only possible redeemer of Amfortas and of -- herself. And now she must lure him to his doom and with it lose her last hope of salvation, now, aye, now -- for even as he mocks her, Klingsor once more waves his hand, castle and keep vanish as if swallowed, up by the earth, and in its place a garden heavy with the scent of gorgeous flowers fills the landscape.

The orchestra, with the Parsifal Motive, gives a spirited description of the brief combat between Parsifal and Klingsor’s knights. It is amid the dark harmonies of the Klingsor Motive that the keep sinks out of sight and the magic garden, spreading out in all directions, with Parsifal standing on the wall and gazing with astonishment upon the brilliant scene, is disclosed.

The Flower Maidens in great trepidation for the fate of their lover knights rush in from all sides with cries of sorrow, their confused exclamations and the orchestral accompaniment admirably enforcing their tumultuous actions.

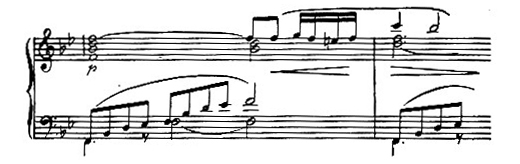

The Parsifal Motive again introduces the next episode, as Parsifal, attracted by the grace and beauty of the girls, leaps down into the garden and seeks to mingle with them. It is repeated several times in the course of the scene. The girls, seeing that he does not seek to harm them, bedeck themselves with flowers and crowd about him with alluring gestures, finally circling around him as they sing this caressing melody:

The effect is enchanting, the music of this episode being a marvel of sensuous grace. Parsifal regards them with childlike, innocent joy. Then they seek to impress him more deeply with their charms, at the same time quarrelling among themselves over him. When their rivalry has reached its height, Kundry’s voice -- "Parsifal, tarry!" -- is wafted from a flowery nook near-by.

"Parsifal!" In all the years of his wandering none has called him by his name; and now it floats toward him as if borne on the scent of roses. A beautiful woman, her arms stretched out to him, welcomes him from her couch of brilliant, redolent flowers. Irresistibly drawn toward her, he approaches and kneels by her side; and she, whispering to him in tender accents, leans over him and presses a long kiss upon his lips. It is the lure that has sealed the fate of many a knight of the Grail. But in the youth it inspires a sudden change. The perilous subtlety of it, that is intended to destroy, transforms the "guileless fool" into a conscious man, and that man conscious of a mission. The scenes he has witnessed in the Grail castle, the stricken King whose wound ever bled afresh, the part he is to play, the peril of the temptation that has been placed in his path-all these things become revealed to him in the rapture of that unhallowed kiss. In vain the enchantress seeks to draw him toward her. He thrusts her from him. Maddened by the repulse, compelled through Klingsor’s arts to see in the handsome youth before her lawful prey, she calls upon the sorcerer to aid her. At her outcry Klingsor appears on the castle wall, in his hand the Spear taken from Amfortas, and, as Parsifal faces him, hurls if full at him. But lo, it rises in its flight and remains suspended in the air over the head of him it was aimed to slay.

Reaching out and seizing it, Parsifal makes with it the sign of the cross. Castle and garden wall crumble into ruins, the garden shrivels away, leaving in its place a sere wilderness, through which Parsifal, leaving Kundry as one dead upon the ground, sets forth in search of the castle of the Grail, there to fulfill the mission with which now he knows himself charged.

Act III. Not until after long wandering through the wilderness, however, is it that Parsifal once more finds himself on the outskirts of the Grail forest. Clad from head to foot in black armour, his visor closed, the Holy Spear in his hand, he approaches the spot where Gurnemanz, now grown very old, still holds watch, while Kundry again in coarse garb, but grown strangely pale and gentle, humbly serves the brotherhood. It is Good Friday morn, and peace rests upon the forest.

Kundry is the first to discern the approach of the black knight. From the tender exaltation of her mien, as she draws Gurnemanz’s look toward the silent figure, it is apparent that she divines who it is and why he comes. To Gurnemanz, however, he is but an armed intruder on sanctified ground and upon a holy day, and, as the black knight seats himself on a little knoll near a spring and remains silent, the old warder chides him for his offence. Tranquilly the knight rises, thrusts the Spear he bears into the ground before him, lays down his sword and shield before it, opens his helmet, and, removing it from his head, places it with the other arms, and then himself kneels in silent prayer before the Spear. Surprise, recognition of man and weapon, and deep emotion succeed each other on Gurnemanz’s face. Gently he raises Parsifal from his kneeling posture, once more seats him on the knoll by the spring, loosens his greaves and corselet, and then places upon him the coat of mail and mantle of the knights of the Grail, while Kundry, drawing a golden flask from her bosom anoints his feet and dries them with her loosened hair. Then Gurnemanz takes from her the flask, and, pouring its contents upon Parsifal’s head, anoints him king of the knights of the Grail. The new king performs his first office by taking up water from the spring in the hollow of his hand an baptizing Kundry, whose eyes, suffused with tears, are raised to him in gentle rapture.

Here is heard the stately Motive of Baptism:

The "Good Friday Spell," one of Wagner’s most beautiful mood paintings in tone color, is the most prominent episode in these scenes.

Once more Gurnemanz, Kundry now following, leads the way toward the castle of the Grail. Amfortas’s aged father, Titurel, uncomforted by the vision of the Grail, which Amfortas, in his passionate contrition, deems himself too sullied to unveil, has died, and the knights having gathered in the great hall, Titurel’s bier is borne in solemn procession and placed upon a catafalque before Amfortas’s couch.

"Uncover the shrine!" shout the knights, pressing upon Amfortas. For answer, and in a paroxysm of despair, he springs up, tears his garment asunder and shows his open wound. "Slay me!" he cried. "Take up your weapons! Bury your sword-blades deep -- deep in me, to the hilts! Kill me, and so kill the pain that tortures me!"

As Amfortas stands there in an ecstasy of pain, Parsifal enters, and, quietly advancing touches the wound with the point of the Spear.

"One weapon only serves to staunch your wounded side -- the one that struck it."

Amfortas’s torture changes to highest rapture. The shrine is opened and Parsifal, taking the Grail, which again radiates with light, waves it gently to and fro, as Amfortas and all the knights kneel in homage to him, while Kundry gazing up to him in gratitude, sinks gently into the sleep of death and forgiveness for which she has longed.

The music of this entire scene floats upon ethereal arpeggios. The Motive of Faith especially is exquisitely accompanied, its spiritual harmonies finally appearing in this form.

There are also heard the Motives of Prophecy and of the Sacrament, as the knights on the stage and the youths and boys in the dome chant. The Grail Motive, which is prominent throughout the scene, rises as if in a spirit of gentle religious triumph and brings, with the Sacrament Motive, the work to a close.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-25 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |