Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > The Mastersingers (Wagner) - Music

The Music of 'The Mastersingers'

(German title: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg)

An Opera by Richard Wagner

Any notice of the music of "The Meistersingers" must necessarily, in a work of this kind, be somewhat brief; for there are so many points of almost equal importance that a detailed analysis would mean many pages of writing and musical illustration.

1968 German stamp celebrating the 100th anniversary of Wagner's opera, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg), and portraying Wagner's signature and an excerpt from the original manuscript, written in Wagner's own handwriting

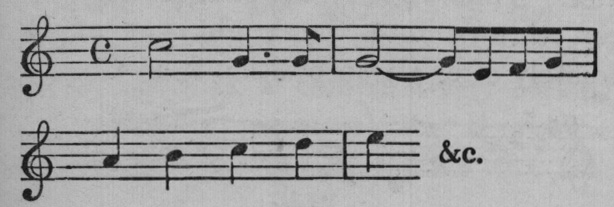

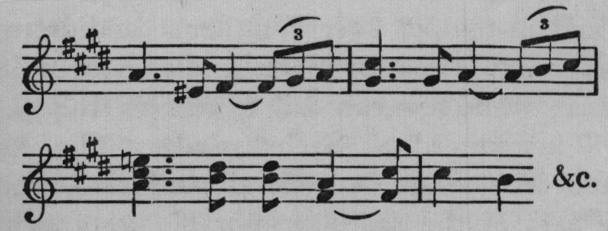

True to his theories, Wagner gives us here no separate songs or detached movements; but one piece leads into another from beginning to end of an Act. The Overture, as in most of the composer’s great music-dramas, is a sort of musical epitome of the entire work. This masterly piece of orchestration tells of the guild, with its cast-iron rules; of Walther’s attempts to gain admission to its conservative circle; and of the ultimate victory of Art over all inartistic barriers. At the opening of the Overture a stately melody is given out, known as the Meistersingers’ motiv, and representing the guild with all its mannerisms and formalities:

A few measures farther on, the sonorous grandeur of the Meistersingers’ March arrests the attention:

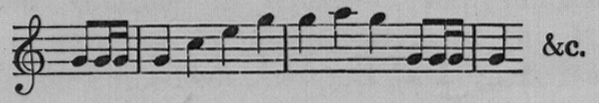

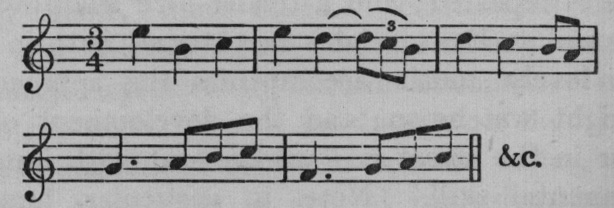

The breadth and wealth of sound which go to make up this part are truly superb: bar follows bar with an ever-increasing richness of melody and orchestration which has rarely been surpassed even by Wagner himself. The second theme is of peculiar interest, because Wagner evolved it from the opening notes of a genuine Meistersinger tune:

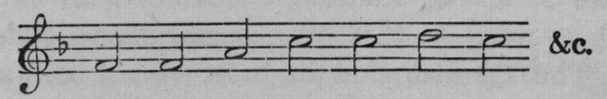

This was Heinrich Müglin’s melody, known among the Mastersingers as the "Long Tone." The listener should understand that Wagner made use of real Meistersinger tunes in his drama, his object being to typify the art represented by the Masters. On the other hand, he employed themes of his own to express the uprising of emotion, as opposed to pedantic rule, in the breast of the young knight Walther. Thus we have the prize love-song of Eva’s admirer, thrown into the bright key of E major immediately after a transposition from C:

Out of this and similar thematic material the Overture is built. An ever-increasing undercurrent of excitement leads up to the climax, when the Meistersingers’ motiv bursts forth again in all its glory. The character of the whole Prelude is, in short, the character of the drama itself -- "a contest of forces with a final reconciliation."

The First Act opens with quite an old-fashioned chorale, sung by choir and congregation. When Eva and Walther are left by themselves for their stolen interview, the "Spring" theme, which plays so important a part in the score, is heard:

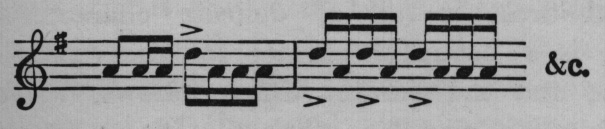

The character of the music changes when David, Sachs’ assistant, enters; the idea being to represent in lively strains the gay, young, irresponsible life of the Meistersinger apprentices. This is clear from the fact that, with the entrance of the Meistersingers, at the close of the scene with David, the music again assumes a comparatively serious cast. When Walther is presented for the contest by Pogner we hear for the first time the following arresting theme of his knighthood, a theme which henceforward accompanies him throughout the score:

Replying to Kothner’s question as to who was his instructor (the Meistersingers spoke of twelve Minnesingers as their masters and models), Walther sings the lyric, "Am stillen Herd," a most exquisite melody, foremost in beauty in all the work. The subsequent trial song "throbs throughout with the Spring theme," above noted. Beckmesser’s discomfiture and ill-temper over Walther’s candidature are admirably expressed by certain dissonances in the orchestra; while few can fail to remark the "kindly theme" introduced as Sachs speaks. The Act, as we have seen, ends in general confusion, and the closing bars of the score are notable for the humorous way in which the bassoons, the clowns of the orchestra, satirise the "ponderous dignity" of the Mesitersingers’ motiv.

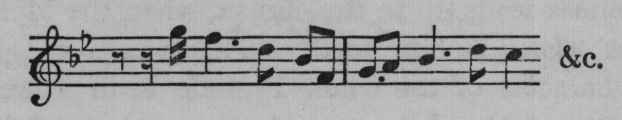

The music of the Second Act is "simplicity itself" up to the appearance of Pogner and Eva. The score is "rich with themes already made known," but when the goldsmith tells his daughter of the plan he has conceived for the disposal of her hand, we hear for the first time, what may be called the Nuremberg motiv, which is to be regarded as expressing the pride of the citizens in their quaint old town:

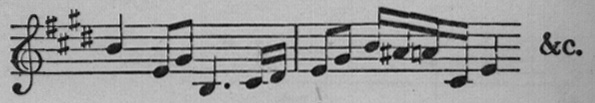

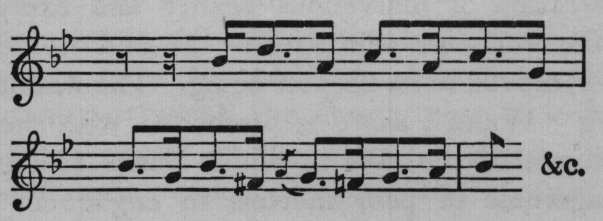

Familiar themes, "employed to make a mood-picture of great beauty," illustrate the scene between Sachs and Eva. When Walther enters, the knight theme is repeated; and a tender love motiv appeals to the ear as Eva declares her eternal faith in him. Some lovely music accompanies the approach of the night watchman; and the development of the uproar in the street is "worked out with immense contrapuntal skill." Note, in particular, how the composer represents the beating of Beckmesser:

When the street is finally cleared of the crowd, the music of the summer night "steals back in an ethereal whisper," and the Act ends with "one of those beautiful points of repose which Wagner knew so well how to make after a movement of extreme agitation."

The Prelude to the Third Act has been described as marking the highest point of the drama. Here, in a creation of marvelous beauty and expressiveness, the composer paints for us the soul of the poet-cobbler, moved to its deepest being. The wonderfully stirring "Wahn" motiv is associated with the great monologue of the Act in which Sachs broods over the eagerness of poor mortals to engage in strife. The scene between Walther and the shoemaker is full of luscious melody. And then, who can miss the "mastersong" which finally wins for Walther the prize?

The scene following Eva’s entrance in her betrothal dress is full of delicate characterisation. There is a beautiful passage for the recitation of Sachs; and the quintet which follows, written in the familiar operatic manner -- that is, in purely lyric style -- is generally allowed to be "one of the loveliest conceptions of this extraordinary work." In the last scene the leading themes of the opera are woven into a marvellous web, twining and winding themselves round Sachs’ address, as if all mankind were thronging to his side.

What shall be said further? A hearing of "The Meistersingers’ emphasises several points. One remarks chiefly the lyric quality of the work -- the charming songs scattered throughout, most of them detachable from the context. We note also the important part which the chorus plays as compared with other works of the master. Again, we see the skill with which Wagner has "caught and reproduced the atmosphere of sixteenth-century Nuremberg without sacrificing a jot of the absolute modernity of his style." The complexity and elaboration of the score are further points of interest. Finally there is the orchestration. Wagner used to be called one of the noisiest of modern composers. One outstanding feature of "The Meistersingers" is, however, the moderation and discretion of its accompaniments. The instrumentation is always rich, often sonorous, very seldom noisy. For example, in the first two pages of the First Act the full orchestra is only used twice -- each time for a few bars; and similar reticence is the characteristic of the whole work. The ingenuity and novelty of the treatment of the wind instruments are above all praise.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |