Music with Ease > 19th Century French Opera > Les Huguenots (Meyerbeer) - Synopsis

Les Huguenots -

Synopsis

(English title: The Huguenots)

An Opera by Giacomo Meyerbeer

CHARACTERS

VALENTINE, daughter of St. Bris……………………. Soprano

MARGUERITE DE VALOIS, betrothed to Henry IV, of Navarre ………………………………………..….. Soprano

URBAIN, page to Marguerite ………………………… Mezzo-Soprano

COUNT DE ST. BRIS, Catholic nobleman …………Baritone

COUNT DE NEVERS, Catholic nobleman …………. Baritone

COSSE……………………………………………………Tenor

MERU, Catholic gentleman ……….……….……….…Baritone

THORE, Catholic gentleman……….……….……….…Baritone

TAVANNES, Catholic gentleman……….……….………Tenor

DE RETZ ………………………………………………… Baritone

RAOUL DE NANGIS, a Huguenot nobleman………….. Tenor

MARCEL,a Huguenot soldier, servant to Raoul………… Bass

Catholic and Huguenot ladies and gentlemen of the court; soldiers, pages, citizens, and populace; night watch, monks, and students.

Place: Touraine and Paris.

Time: August, 1572.

It has been said that, because Meyerbeer was a Jew, he chose for two of his operas, "Les Huguenots" and "Le Prophète," subjects dealing with bloody uprising due to religious differences among Christians. "Les Huguenots" is written around the massacre of the Huguenots by the Catholics, on the night of St. Bartholomew’s, Paris, August 24, 1572; "Le Prophète" around the seizure and occupation of Munster, in 1555, by the Anabaptists, led by John of Leyden. Even the ballet of the spectral nuns, in "Robert le Diable," has been suggested as due to Meyerbeer’s racial origin and a tendency covertly to attack the Christian religion. Far-fetched, I think. Most likely his famous librettist was chiefly responsible for choice of subjects and Meyerbeer accepted them because of the effective manner in which they were worked out. Even so, he was not wholly satisfied with Scribe’s libretto of "Les Huguenots." He had the scene of the benediction of the swords enlarged, and it was upon his insistence that Deschamps wrote in the love duet in Act IV. As it stands, the story has been handled with keen appreciation of its dramatic possibilities.

Act I. Touraine. Count de Nevers, one of the leaders of the Catholic party, has invited friends to a banquet at his chateau. Among these is Raoul de Nangis, a Huguenot. He is accompanied by an old retainer, the Huguenot soldier, Marcel. In the course of the fête it is proposed that everyone shall toast his love in a song. Raoul is the first to be called upon. The name of the beauty whom he pledges in his toast is unknown to him. He had come to her assistance while she was being molested by a party of students. She thanked him most graciously. He lives in the hope of meeting her again.

Marcel is a fanatic Huguenot. Having followed his master to the banquet, he finds him surrounded by leaders of the party belonging to the opposite faith. He fears for the consequences. In strange contrast to the glamour and gaiety of the festive proceedings, he intones Luther’s hymn, "A Stronghold Sure." The noblemen of the Catholic party instead of becoming angry are amused. Marcel repays their levity by singing a fierce Huguenot battle song. That also amuses them.

At this point the Count de Nevers is informed that a lady is in the garden and wishes to speak with him. He leaves his guests who, through an open window, watch the meeting. Raoul, to his surprise and consternation, recognizes in the lady none other than the fair creature whom he saved from the molestations of the students and with whom he has fallen in love. Naturally, however, from the circumstances of her meeting with de Nevers he cannot but conclude that a liaison exists between them.

De Nevers returns, rejoins his guests. Urbain, the page of Queen Marguerite de Valois, enters. He is in search of Raoul, having come to conduct him to a meeting with a gracious and noble lady whose name, however, is not disclosed. Raoul’s eyes having been bandaged, he is conducted to a carriage and departs with Urbain, wondering what his next adventure will be.

Act II. In the garden of Chenonçeaux, Queen Marguerite de Valois receives Valentine, daughter of the Count de St. Bris. The Queen knows of her rescue from the students by Raoul. Desiring to put an end to the differences between Huguenots and Catholics, which have already led to bloodshed, she has conceived the idea of uniting Valentine, daughter of one of the great Catholic leaders, to Raoul. Valentine, however, was already pledged to de Nevers. It was at the Queen’s suggestion that she visited de Nevers and had him summoned from the banquet in order to ask him to release her from her engagement to him -- a request which, however reluctantly, he granted.

Here, in the Gardens of Chenonçeaux, Valentine and Raoul are, according to the Queen’s plan, to meet again, but she intends first to receive him alone. He is brought in, the bandage is removed from his eyes, he does homage to the Queen, and when, in the presence of the leaders of the Catholic party, Marguerite de Valois explains her purpose and her plan through this union of two great houses to end the religious differences which have disturbed her reign, all consent.

Valentine is led in. Raoul at once recognizes her as the woman of his adventure but also, alas, as the woman whom de Nevers met in the garden during the banquet. Believing her to be unchaste, he refuses her hand. General consternation. St. Bris, his followers, all draw their swords. Raoul’s flashes from its sheath. Only the Queen’s intervention prevents blooshed.

Act III. The scene is an open place in Paris before a chapel, where de Nevers, who has renewed his engagement with Valentine, is to take her in marriage. The nuptial cortege enters the building. The populace is restless, excited. Religious differences still are the cause of enmity. The presence of Royalist and Huguenot soldiers adds to the restlessness of the people. De Nevers, St. Bris, and another Catholic nobleman, Maurevert, come out from the chapel, where Valentine has desired to linger in prayer. The men are still incensed over what appears to them the shameful conduct of Raoul toward Valentine. Marcel at that moment delivers to St. Bris a challenge from Raoul to fight a duel. When the old Huguenot soldier has retired, the noblemen conspire together to lead Raoul into an ambush. During the duel, followers of St. Bris, who have been placed in hiding, are suddenly to issue forth and murder the young Huguenot nobleman.

From a position in the vestibule of the chapel, Valentine has overheard the plot. She still loves Raoul and him alone. How shall she warn him of the certain death in store for him? She sees Marcel and counsels him that his master must not come here to fight the duel unless he is accompanied by a strong guard. As a result, when Raoul and his antagonist meet, and St. Bris’s soldiers are about to attack the Huguenot, Marcel summons the latter’s followers from a nearby inn. A street fight between the two bodies of soldiers is imminent, when the Queen and her suite enter. A gaily bedecked barge comes up the river and lays to at the bank. It bears de Nevers and his friends. He has come to convey his bride from the chapel to his home. And now Raoul learns, from the Queen, and to his great grief, that he has refused the hand of the woman who loved him and who had gone to de Nevers in order to ask him to release her from her engagement with him.

Act IV. Raoul seeks Valentine, who has become the wife of de Nevers, in her home. He wishes to be assured of the truth of what he has heard from the Queen. During their meeting footsteps are heard approaching and Valentine barely has time to hide Raoul in an adjoining room when de Nevers, St. Bris, and other noblemen of the catholic party enter, and form a plan to be carried out that very night -- the night of St. Bartholomew -- to massacre the Huguenots. Only de Nevers refuses to take part in the conspiracy. Rather than do so, he yields his sword to St. Bris and is led away a prisoner. The priests bless the swords, St. Bris and his followers swear loyalty to the bloody cause in which they are enlisted, and depart to await the order to put it into effect, the tolling of the great bell from St. Germain.

Raoul comes out from his place of concealment. His one thought is to hurry away and notify his brethren of their peril. Valentine seeks to detain him, entreats him not to go, since it will be to certain death. As the greatest and final argument to him to remain, she proclaims that she loves him. But already the deep-voiced bell tolls the signal. Flames, blood-red, flare through the windows. Nothing can restrain Raoul from doing his duty. Valentine stands before the closed door to block his egress. Rushing to a casement, he throws back the window and leaps to the street.

Act V. Covered with blood, Raoul rushes into the ballroom of the Hotel de Nesle, where the Huguenot leaders, ignorant of the massacre that has begun, are assembled, and summons them to battle. Already Coligny, their great commander, has fallen. Their followers are being massacred.

The scene changes to a Huguenot churchyard, where Raoul and Marcel have found temporary refuge. Valentine hurries in. She wishes to save Raoul. She adjures him to adopt her faith. De Nevers has met a noble death and she is free-free to marry Raoul. But he refuses to marry her at the sacrifice of his religion. Now she decides that she will die with him and that they will both die as Huguenots and united. Marcel blesses them. The enemy has stormed the churchyard and begins the massacre of those who have sought safety there and in the edifice itself. Again the scene changes, this time to a square in Paris. Raoul, who has been severely wounded, is supported by Marcel and Valentine. St. Bris and his followers approach. In answer to St. Bris’s summons, "Who goes there?" Raoul, calling to his aid all the strength he has left, cries out, "Huguenots." There is a volley. Raoul, Valentine, Marcel lie dead on the ground. Too late St. Bris discovers that he has been the murderer of his own daughter.

Originally in five acts, the version of "Les Huguenots" usually performed contains but three. The first two acts are drawn into one by converting the second act into a scene and adding it to the first. The fifth act (or in the usual version the fourth) is nearly always omitted. This is due to the length of the opera. The audience takes it for granted that, when Raoul leaves Valentine, he goes to his death. I have seen a performance of "Les Huguenots" with the last act. So far as an understanding of the work is concerned, it is unnecessary. It also involves as much noise and smell of gunpowder as Massenet’s opera, "La Navarraise" -- and that is saying a good deal.

The performances of "Les Huguenots," during the most brilliant revivals of the work at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, under Maurice Grau, were known as "les nuits de sept étoiles" (the nights of the seven stars). The cast to which the performances owed this designation is given in the summary above. A manager, in order to put "Les Huguenots" satisfactorily upon the stage, should be able to give it with seven first-rate principals, trained as nearly as possible in the same school of opera. The work should be sung preferably in French and by singers who know something of the traditions of the Grand Opéra, Paris. Mixed casts of Latin and Teutonic singers mar a performance of this work. If "Les Huguenots" appears to have fallen off in popularity since "the nights of the seven stars," I am inclined to attribute this to inability or failure to give the opera with a cast either as fine or as homogeneous as that which flourished at the Metropolitan during the era of "les nuits de sept étoiles," when there not only were seven stars on the stage, but also seven dollars in the box office for every orchestra stall that was occupied -- and they all were.

Auber’s "Masaniello," Rossini’s "William Tell," Halévy’s "La Juive," and Meyerbeer’s own "Robert le Diable" practically having dropped out of the repertoire in this country, "Les Huguenots," composed in 1836, is the earliest opera in the French grand manner that maintains itself on the lyric stage of America -- the first example of a school of music which, through the "Faust" of Gounod, the "Carmen" of Bizet, and the works of Massenet, has continued to claim our attention.

After a brief overture, in which Luther’s hymn is prominent, the first act opens with a sonorous chorus for the banqueters in the salon of de Never’s castle. Raoul, called upon to propose in song a toast to a lady, pledges the unknown beauty, whom he rescued from the insolence of a band of students. He does this in the romance, "Plus blanche que la plus blanche hermine" (Whiter than the whitest ermine). The accompaniment to the melodious measures, with which the romance opens, is supplied by a viola solo, the effective employment of which in this passage shows Meyerbeer’s knowledge of the instrument and its possibilities. This romance is a perfect example of a certain phase of Meyerbeer’s act -- a suave and elegant melody for voice, accompanied in a highly original manner, part of the time, in this instance, by a single instrument in the orchestra, which, however, in spite of its effectiveness, leaves an impression of simplicity not wholly uncalculated.

Raoul’s romance is followed by the entrance of Marcel, and the scene for that bluff, sturdy old Huguenot campaigner and loyal servant of Raoul, a splendidly drawn character, dramatically and musically. Marcel tries to drown the festive sounds by intoning the stern phrases of Luther’s hymn. This he follows with the Huguenot battle song, with its "Piff, piff, piff," which has been rendered famous by the great bassos who have sung it, including, in this country, Formes and Edouard de Reszke.

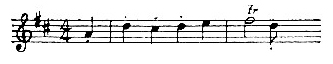

De Nevers then is called away to his interview with the lady, who Raoul recognizes as the unknown beauty rescued by him from the students, and whom, from the circumstances of her visit to de Nevers, he cannot but believe to be engaged in a liaison with the latter. Almost immediately upon de Nevers’s rejoining his guests there enters Urbain, the page of Marguerite de Valois. He greets the assembly with the brilliant recitative, "Nobles Seigneurs salut!" This is followed by a charming cavatina, "Une dame noble et sage" (A wise and noble lady). Originally this was a soprano number, Urbain having been composed as a soprano role, which it remained for twelve years. Then in 1844, when "Les Huguenots" was produced in London, with Alboni as Urbain, Meyerbeer transposed it, and a contralto, or mezzo-soprano, part it has remained ever since, its interpreters in this country having included Annie Louise Cary, Trebelli, Scalchi, and Homer. The theme of "Une dame noble et sage" is as follows:

The letter brought by Urbain is recognized by the Catholic noblemen as being in the handwriting of Marguerite de Valois. As it is addressed to Raoul, they show by their obsequious demeanour toward him the importance they attach to the invitation. In accordance with its terms Raoul allows himself to be blindfolded and led away by Urbain.

Following the original score and regarding what is now the second scene of Act I as the second act, this opens with Marguerite de Valois’s apostrophe to the fair land of Touraine (O beau pays de la Touraine), which, with the air immediately following, "A ce mot tout s’anime et renait la nature" (At this word everything revives and Nature renews itself),

constitutes an animated and brilliant scene for coloratura soprano.

There is a brief colloquy between Marguerite and Valentine, then the graceful female chorus, sung on the bank of the Seine and known as the "bathers’ chorus," this being followed by the entrance of Urbain and his engaging song -- the rondeau composed for Alboni -- "Non! -- non, non, non, non, non,! Vous n’avey jamais, je gage" (No! -- no, no, no, no, no! You have never heard, I wager).

Raoul enters, the bandage is removed from his eyes, and there follows a duet, "Beauté divine, enchanteresse" (Beauty brightly divine, enchantress), between him and Marguerite, all graciousness on her side and courtly admiration on his. The nobles and their followers come upon the scene. Marguerite de Valois’s plan to end the religious strife that has distracted the realm meets with their approbation. The finale of the act begins with the swelling chorus in which they take oath to abide by it. There is the brief episode in which Valentine is led in by St. Bris, presented to Raoul, and indignantly spurned by him. The act closes with a turbulent ensemble. Strife and bloodshed, then and there, are averted only by the interposition of Marguerite.

Act III opens with the famous chorus of the Huguenot soldiers in which, while they imitate with their hands the beating of drums, they sing their spirited "Rataplan." By contrast, the Catholic maidens, who accompany the bridal cortege of Valentine and de Nevers to the chapel, intone a litany, while Catholic citizens, students, and women protest against the song of the Huguenot soldiers. These several choral elements are skillfully worked out in the score. Marcel, coming upon the scene, mamages to have St. Bris summoned from the chapel, and presents Raoul’s challenge to a duel. The Catholics form their plot to assassinate Raoul, of which Valentine finds opportunity to notify Marcel, in what is one of the striking scenes of the opera The duel scene is preceded by a stirring septette, a really great passage, "En mon bon droit j’ai confiance" (On my good cause relying). The music, when the ambuscade is uncovered and Marcel summons the Huguenots to Raoul’s aid, and a street combat is threatened, reaches an effective climax in a double chorus. The excitement subsides with the arrival of Marguerite de Valois, and of the barge containing de Nevers and his retinue. A brilliant chorus, supported by the orchestra and by a military band on the stage, with ballet to add to the spectacle forms the finale, as de Nevers conducts Valentine to the barge, and is followed on board by St. Bris and the nuptial cortege.

The fourth act, in the home of de Nevers, opens with a romance for Valentine, "Parmi les pleurs mon rêve se ranine" (Amid my tears, by dreams once more o’ertaken), which is followed by a brief scene between her and Raoul, whom the approach of the conspirators quickly obliges her to hide in an adjoining apartment. The scene of the consecration of the swords is one of the greatest in opera; but that it shall have its full effect St. Bris must be an artist like Plaçon, who, besides being endowed with a powerful and beautifully managed voice, was superb in appearance and as St. Bris had the bearing of the dignified, commanding yet fanatic nobleman of old France. Musically and dramatically the scene rests on St. Bris’s shoulders, and broad they must be, since his is the most conspicuous part in song and action, from the intonation of his solo, "Pour cette cause sainte, obeisses san crainte" (With sacred zeal and ardor let now your soul be burning),

to the end of the savege stretta, when, the conspirators, having tiptoed almost to the door, in order to disperse for their mission, suddenly turn, once more uplift sword hilts, poignards, and crucifixes, and after a frenzied adjuration of loyalty to a cause that demands the massacre of an unsuspecting foe, steal forth into the shades of fateful night.

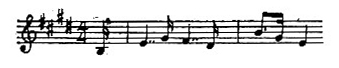

Powerful as this scene is, Meyerbeer has made the love duet which follows even more gripping. For now he interprets the conflicting emotions of love and loyalty in two hearts. It begins with Raoul’s exclamation, "Le danger presse et le temps vole, laisse moi partir" (Danger presses and time flies. Let me depart), and reaches its climax in a cantilena of supreme beauty, "Tu l’as dit, oui tu m’aimes" (Thou hast said it; aye, thou lov’st me).

which is broken in upon by the sinister tolling of a distant bell -- the signal for the massacre to begin. An air for Valentine, an impassioned stretta for the lovers, Raoul’s leap from the window, followed by a discharge of musketry, from which, in the curtailed version, he is supposed to meet his death, and this act, still an amazing achievement in opera, is at an end.

In the fifth act, there is the fine scene of the blessing by Marcel of Raoul and Valentine, during which strains of Luther’s hymn are heard, intoned by Huguenots, who have crowded into their church for a last refuge.

"Les Huguenots" has been the subject of violent attacks, beginning with Robert Schumann’s essay indited as far back as 1837, and starting off with the assertion, "I feel today like the young warrior who draws his sword for the first time in a holy cause." Schumann’s most particular "holy cause" was, in this instance, to praise Mendelssohn’s oratorio, "St. Paul," at the expense of Meyerbeer’s opera "Les Huguenots," notwithstanding the utter dissimilarity of purpose in the two works. On the other hand Hanslick remarks that a person who cannot appreciate the dramatic power of this Meyerbeer opera, must be lacking in certain elements of the critical faculty. Even Wagner, one of Meyerbeer’s bitterest detractors, found words of the highest praise for the passage from the love duet, which is quoted immediately above. The composer of "The Ring of the Nibelung" had a much broader outlook upon the world than Schumann, in whose genius there was, after all, a good deal of the bourgeois.

Pro or con, when "Les Huguenots" is sung with a fully adequate cast, it cannot fail of making a deep impression -- as witness "les nuits de sept étoiles."

A typical night of the seven stars at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, was that of December 26, 1894. The sept étoiles were Nordica (Valentine), Scalchi (Urbain), Melba (Marguerite de Valois), Jean de Reszke (Raoul), Plançon (St. Bris), Maurel (de Nevers), and Edouard de Reszke (Marcel). Two Academy of Music casts are worth referring to. April 30, 1872, Parepa Rosa, for her last appearance in America, sang Valentine. Wachtel was Raoul and Santley St. Bris. The other Academy cast was a "Night of six stars," and is noteworthy as including Maurel twenty years, almost to the night, before he appeared in the Metropolitan cast. The date was December 24, 1874. Nilson was Valentine, Cary Urbain, Maresi Marguerite de Valois, Campanini Raoul, Del Puente St. Bris. Maurel de Nevers, and Nanetti Marcel. With a more distinguished Marguerite de Valois, this performance would have anticipated the "nuits de sept étoiles."

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |