Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > The Twilight of the Gods (Wagner)

The Twilight of the Gods

(German title: Götterdammerung)

An Opera by Richard Wagner

Dramatis Personae

SIEGFRIED

GUNTHER, the Gibichung

GUTRUNE, his Sister

HAGEN, Half-brother to Gunther and Son of Alberich

ALBERICH

BRÜNNHILDE

The Rhine Norns

The Rhine-Maidens

WALTRAUTE

Chorus of Vassals and Women

Plot and Music of The Twilight of the Gods

This, the last drama of the cycle, opens with a prologue on the summit of Brünnhilde’s rock. It is night, with the yellow glow of the fire in the background. The three Norns, goddesses of Fate, born of Erda "before the world was," are discovered spinning the web of destiny; peering into the past, the present, and the future. The scene, as has often been remarked, has no close dramatic relation to the drama about to be enacted; but is rather "a pictorial and musical mood tableau, designed to fill the mind of the auditor with portents." While the Norns are endeavouring to fathom the outcome of the curse on the ring, the cord which they have been spinning suddenly snaps. The Norns pick up the broken pieces of thread, and with frightened cries disappear into the earth.

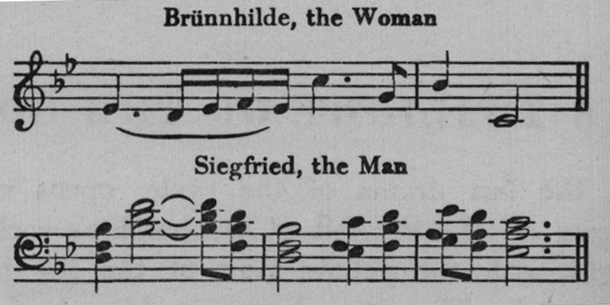

Now the day dawns, and Siegfried and Brünnhilde come forth from their cavern-home -- he in full armour (hers, by the way), she leading her horse, Grane. Here two new motives indicating the altered characters of the pair are heard -- those of Brünnhilde, the woman, and Siegfried, the mature hero:

The first of these, to quote Mr. Henderson again, expresses very beautifully the loving, clinging nature of the Valkyrie. The second is a thematic development of the motive of Siegfried, the youth. The change is chiefly one of rhythm. Siegfried, the youth, is depicted musically in six-eight measure, a rhythm buoyant and piquant. For Siegfried, the mature hero, the melodic sequence is preserved, but the rhythm is changed to a duel one. The change is one founded on the nature of music, for the dual rhythm is firm, square, and solid. The injection of minor harmony at the end is heard in the first announcement of this theme, and serves to indicate approaching sorrow. This motive rises to its grandest development in the funeral march after Siegfried’s death, when the orchestra passes in review, in a composition of wonderful beauty and power , the themes most closely associated with him. But we are anticipating.

Brünnhilde and Siegfried are before us. She is sending him forth to new exploits of valour; fearing, however, that, having given him all, she may not be able to hold his heart in absence.

My wisdom fails,

But good-will remains;

So full of love

But failing in strength,

Thou wilt despise

Perchance to the poor one,

Who, having giv’n all,

Can grant thee no more.

Siegfried assures her of his lasting affection, and, as a pledge of his fidelity, he gives her the ring, adding the story of his winning it from the dragon, and bidding her preserve it as a wedding charm. Brünnhilde rapturously accepts the fateful gift, and in return makes over to Siegfried her horse Grane, who has, with herself, lost all his necromantic powers. His reply reveals how much he owes to her: "Thy noble steed bestriding, and with thy sheltering shield, now am I Siegfried no more: I am but Brünnhilde’s arm." Siegfried now sets out in search of adventure, and the scene changes as the sounds of his horn gradually die away in the distance, echoing down the Rhine valley.

After an orchestral interlude depicting the journey of the hero, the First Act opens in the hall of the Gibichungs near the Rhine. Here Siegfried finds Gunther, the son of Gibich, seated at a table with his sister Gutrune, and his half-brother Hagen. Hagen is the son of the Nibelung Alberich -- "the anger-begotten son of Love’s dark enemy" -- and the object of his sojourn among men is to regain for his father possession of the ring. Accordingly, he is plotting for the downfall of Siegfried, with Gunther and Gutrune as abettors. In pursuance of his design, he brews Seigfried a magic potion, by virtue of which Siegfried forgets his troth plighted to Brünnhilde, and becomes deeply enamoured of the maidenly charms of Gutrune. Hagen suggests that in exchange for Gutrune, Siegfried shall bring Brünnhilde to be Gunther’s bride; and Siegfried, assuming Gunther’s form by the power of his Tarnhelm cap, returns to Brünnhilde’s rock, and compels her by the force of his arm to share his couch. After snatching the ring from her finger, he leads her off to his new friend.

"Why does Brünnhilde so speedily submit to the disguised Siegfried?" asks Wagner himself. "Just because he had torn from her the ring, in which alone she treasured up her strength. The terror, the demoniacal character of the whole scene must be noted. Through the flames fore-doomed for Siegfried alone to pass, the fire which experience has shown that he alone could pass, there strides to her, with small ado -- another. The ground reels beneath Brünnhilde’s feet, the world is out of joint; in a terrible struggle she is overpowered, she is ‘forsaken by God.’ Moreover, it is Siegfried, in reality, whom (unconsciously, but all the more bewilderingly) despite his mask, she -- almost -- recognises by his flashing eye."

Once more, in the Second Act, we return to the banks of the Rhine, to the castle of Gunther, whither Brünnhilde has been dragged. It begins with the appearance of Alberich, who is inciting Hagen to further efforts towards regaining the ring. On Brünnhilde’s arrival, she is met by Siegfried in his own form; and, perceiving the ring on his finger, she inquires of him how he comes to be wearing the circlet which Gunther had so lately wrenched from her finger. "Ha!" she exclaims. "That ring upon his hand! His -- ? Siegfried’s -- ?" No satisfactory answer us forthcoming, and she bursts out with the charge that not Gunther but Siegfried married her. "He forced delights of love from me!" she cries. She accuses Siegfried of perjury, and although he protests his innoncence, she soon convinces Gunther, and together with Hagen, they deliberate about Siegfried’s destruction. Siegfried must die -- that is the decision. Hagen shouts in triumph; the ring and its power will soon be his.

The Third and last Act shows the three Rhine-maidens disporting themselves in the water in a cove of the river. "Queen Sun, send us the hero who again our gold will give us!" they sing. Siegfried, who has been hunting in the forest, and has strayed from his comrades, shows himself, in full armour, on the rocks above them. They implore him to return the ring, which he is wearing, but he keeps it in spite of their warning him of the curse attached to it. Siegfried’s hunting companions appear on the scene, and, while they rest, he recounts the adventures of his past life. As the story is about to touch his first meeting with Brünnhilde, "old memories seem to rise before his mind. They grow more vivid with every new incident he relates, and the moment he mentions the name of his love, the veil is torn asunder, and the consciousness of his deed and his loss stands before his eyes."

Alas! this moment is to be his last. As he ends his late, two ravens, the birds of Wotan, fly over his head. He turns to look at them. Hagen plunges his spear into Siegfried’s back, the only vulnerable part of his body, and the hero dies apostrophizing his Valkyr love. Siegfried has fallen a victim to the curse of the gold.

In the grand final scene, the body of Siegfried is borne back through the moonlight forest to the Hall of the Gibichungs, to the solemn strains of one of the most impressive of dead marches. The bleeding corpse is laid at the feet of Gutrune, the unsuspecting wife. A wild boar has killed her lord, is Hagen’s explanation. When the body is brought in, Hagen reaches for the ring, but the dead hand is raised in solemn warning, and Hagen staggers back, terrified and abashed.

At this juncture, Bruunhilde, who has been assured by the Rhine-maidens that Siegfried’s acts were due to the magic potion, enters the hall, thrusting the weeping Gutrune aside. She claims for herself the sole right of a wife’s grief; and, taking the ring from Siegfried’s finger, she places it upon her own. A funeral pyre has been reared, on which lies the body of her beloved Siegfried. Him she will join in his fiery grave; and when she is reduced to ashes, the Rhine-maidens may once more possess themselves of the ring.

Lighting the fire herself, she mounts her horse Grane, and rushes into the flames. The waters of the Rhine rise to overflowing, invading the hall. Hagen vainly attempts to secure the ring, and is swept away by the flood, while the Rhine-maidens regain the coveted circlet. Meanwhile, the sky has become overspread by a ruddy glow: Walhalla is in flames, and with its destruction go the old gods, whose ill-gotten power yields before the might of human love. "The ancient heaven, sapped by the lust of gold, has crumbled, and a new world, founded upon self-sacrificing love, rises from its ashes to usher in the era of freedom." So ends the great music epic of "The Ring," the grandest achievement in the annals of opera.

The music "hurries the auditor along from one incident to another, and is replete with significant motives poetic fervour." According to M. Saint-Saens, the eminent French composer, it trebles the intensity of the feelings with which the characters are animated. "From the elevation of the last Act," he says, "the whole work appears, in its almost supernatural grandeur, like the chain of the Alps seen from the summit of Mont Blanc." Every scene and every note has, as Mr. Elson says, its own meaning. The gloomy music of the Norns, the great duet of farewell between Siegfried and Brünnhilde, and the well-wrought Rhine journey are all thoroughly effective. So, too, is the chorus of homage to Gunther, and the many dramatic passages in the Hall of the Gibichungs. But undoubtedly the greatest single Act in all Wagner’s works is the closing one of the trilogy, for here is found the delicious trio of the Rhine-maidens, the wonderful funeral march of Siegfried, and the dramatic climax of Brünnhilde’s tragic fate. The final scene is one of "unequalled breadth and power," forming a worthy and majestic close to the most stupendous music-drama that has ever been staged.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |