Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > The Rhinegold (Wagner)

The Rhinegold

(German title: Das Rheingold)

An Opera by Richard Wagner

Dramatis Personae

WOTAN, the chief of the Gods

FRICKA, his Wife

ALBERICH, Chief of the Nibelungs or Gnomes

MIME, his Brother

LOGE, the Fire-god

FROH, the God of Youth

DONNER, the God of Strength

FREIA, the Goddess of Love and Beauty

FASOLT, Giant

FAFNER, Giant

ERDA, the All-Wise Mother Earth

WOGLINDE, Rhine Maiden

WELLGUNDE, Rhine Maiden

FLOSSHILDE

1933 German postage stamp depicting a scene from Wagner's opera, Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold).

Plot and Music of The Rhinegold

It is of essential importance to understand clearly the story of "The Rhinegold," since it forms the basis, the motive of the entire cycle of "The Ring." I shall therefore outline it in some detail.

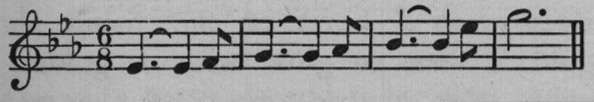

There is little to say about the musical introduction. It is founded on the chord of E flat, given out at first in long-drawn notes, which soon dissolve into shorter rhythmical formations, rising and falling alternately from the lowest to the highest octaves, like the murmuring waves of a rapid river. It introduces the first guiding theme of the drama, the motive of the primeval elements, which plays an important part throughout:

This gentle, melodious phrase is gradually developed until the curtain rises.

Then we see the bed of the Rhine, amongst the rocks and cliffs of which the three Rhine-maidens, Woglinde, Wellgunde, and Flosshilde, guardians of the Rhinegold, are swimming to and fro, singing their cabalistic songs as they disport themselves around the particular rock on which is deposited the mysterious treasure; accompanied always by the gentle, wavy notes of the orchestra. Their undulating gambols are soon interrupted by the appearance of Alberich, the prince of the Nibelungs (strange dwarf people who dwell in the bowels of the earth), a mischievous gnome, who, ascending from the dark regions of his nebulous kingdom, is filled with amorous longing for the lovely naiads of the Rhine. A playful scene ensues. Alberich clumsily tries to catch first one and then another of the nymphs. Sport and mockery are his only reward. Despair and rage follow as he continues to be tricked by the gracefully elusive maidens. The musical accompaniment to this scene is of extreme delicacy, of almost cloying sweetness; notably the mock tenderness of the girls finds an expression, the sly humour of which little forebodes the grave, tragical accents soon to follow.

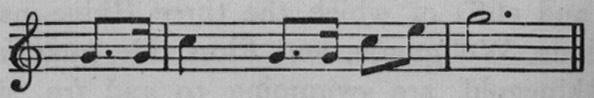

Suddenly, at a burst of the rising sun, the Rhinegold is seen to glow with a golden light, brightening the somber green of the waves as with a tinge of fire. As the gold discloses itself, we hear this theme, given out in stirring tones by the orchestra --

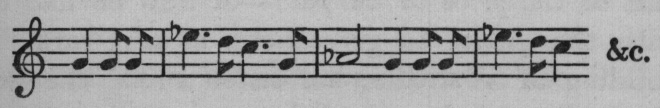

The Undines greet the appearing gold with shouts of joyful acclamation, gleefully singing as they circle round the rock. Alberich is stunned by the splendour of the golden illumination. He demands to know what is means. Incautiously the maidens inform him that he who gains this glittering hoard, should he weld it into a ring, will become lord of the wide world. There is, however, an important condition (and this is one of Wagner’s most poetic and original touches) -- no one can wield the power of the possession unless he renounces for ever the delights of love, cursing and abjuring all the joys of that master passion. Here the listener should note the striking Renunciation of Love theme, which constantly recurs in the course of the tragedy; not necessarily always in connection with the ring, but always in connection with Renunciation in one form or another --

It is, the girls teasingly add, a hopeless case for the love-sick dwarf. But Alberich sees it otherwise. He has failed in his attempt to win one of the Undines. Now he is smitten with the lust for boundless power; and in a fit of frenzy, uttering the awful cry, "Love I forswear for ever," he climbs the rock, tears away the shining treasure, and vanishes amid a scene of the wildest confusion. Night closes in; darkness envelops the stage; the wailing of the dismayed Rhine-maidens, mourning for their guardian gold, is alone heard in the gloom.

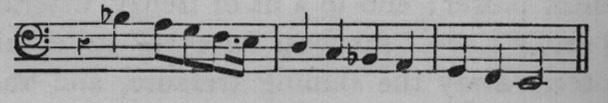

From the depths of the Rhine we are now transferred to a high ridge of mountains, at the foot of which is a grassy plateau. Walhalla, the destined abode of the gods, is seen in the distance, its stately pinnacles piercing the sky. In the foreground Wotan, the supreme god of Northern mythology, lies asleep in the flowery meadow, his wife Fricka, the Teutonic equivalent of Juno, by his side. A solemn melody, expressive of divine splendour and dignity, is here emitted from the orchestra. Wotan speaks in his dream, telling of the palace built for him by the giants, Fafner and Fasolt, as at once the symbol and safeguard of his power. Fricka wakes him from his fond delusions. She reminds him of the price to be paid -- of how he had agreed with the giants to give them, as a reward for the building of Walhalla, her sister Freia, the goddess of youth and love and beauty. It is now that we hear the following emphatic descending figure, motive of the treaty; a figure reiterated again and again whenever Wotan’s freedom of action is hampered --

Fricka proceeds to explain how she had "urged the building of Walhalla in the hope that it might allure Wotan to rest, and reproaches him with having sacrificed to the desire of might and power the worth of womanly love." Freia herself now enters, pursued by Fasolt and Fafner, who come to demand their pay.

Wotan tells them they cannot have Freia; the giants remonstrate, insisting on the bond. A long and warm discussionensues. The giants advance menacingly towards Freia; two other mighty gods, Donner and Froh, brothers of Freia, come hastily to her assistance. The giants are prepared to fight for their rights, but the entrance of Loge, the fire god, effects a diversion. Loge tells how he has searched in vain for a ransom for Freia. Nothing has he discovered in the whole universe, he says, to rival in a man’s mind woman’s "worth and wonder." He goes on to tell how only one man had forsworn love, that same Alberich who stole the treasure-trove, the Rhinegold, from the Rhine-daughters. Then he explains the uses to which the gold (meanwhile fashioned into a ring by Alberich) may be put. Froh suggests the rape of the ring from Alberich. Only this ring, Loge adds, can compensate the heart for the loss of love’s pleasures.

Gods and goddesses listen eagerly to his description. The potent power of the gold and its splendour moves their innermost desire; even the giants cannot resist its temptation. For this gold, they declare, they will forego their lovely prey. But Wotan’s pride revolts at the idea of his becoming the tool of the giants in depriving Alberich of his spoil. He declines to give up Freia; where upon the giants carry off Freia, dragging their way over stock and stone down to the valley of the Rhine.

Here the scene changes: a pale mist obscures the stage, giving an old and worn aspect to the gods. Loge tauntingly reminds the gods that they have not that day tasted the apples of Freia’s garden -- the magic fruits of the goddess of youth, which alone secure the gods from the influence of time. This animates Wotan with a sudden resolution. To preserve his eternal youth, he will waive his dignity. Wotan and Loge then set out for Alberich’s kingdom, determined to possess themselves of the ring by force or subterfuge.

Here, as Dr. Hueffer observes, we touch upon one of the keynotes of the whole drama. The gods, by their desire of splendour, have incurred a debt to their enemies the giants; to pay this, they are now intent on "theft from the thief," their object being, not to return the spoil to the lawful owners, as becomes their office, but to buy back their forfeited youth. In this act of wilful selfishness lies the germ of their doom.

The next scene is marked by broad touches of primitive coarseness. The prelude, with its pronounced rhythmical accents, and its noise of hammers and anvils behind the scenes, indicates that we are nearing Nibelheim, the country of Alberich, the home of the Nibelungs. The vapour thickens and fills the stage. A subterranean cavern is dimly discerned, from one of the passages of which Alberich emerges, dragging with him his shrieking brother, Mime. Mine, the cleverest smith of them all, has been endeavouring to conceal, for his own benefit, a magic cap wrought of the Rhinegold, and known as the Tarnhelm. The Tarnhelm may be regarded as the Northern equivalent of Perseus’ helmet. It renders its wearer invisible, and enables him to assume any form he pleases, as well as to travel to any distance in a moment of time. Cruel flagellations, alternating with the howls of the victims, are here most realistically depicted by the music; the grotesqueness of the whole scene being in exquisite contrast with the passionate but aristocratic bearing of the upper gods.

Loge and Wotan descend above to find Mime groaning on the floor of the cavern, bemoaning his fate. They question him, and are told how Alberich, by the power of the ring, compels the Nibelungs to do his bidding, and has thus forced him to make the Tarnhelm. Alberich now reappears, urging before him a crowd of Nibelungs laden with gold and silver, which they pile in a heap under his directions. Loge acts on Alberich’s vanity by throwing out doubts as to the boasted virtues of the Tarnhelm. Taken thus unawares, Alberich first changes himself into a monstrous snake and then into a toad. "Catch it, quick!" says Loge to Wotan, who thereupon sets his foot on the toad, while at the same time Loge snatched the vaunted cap from its head. Alberich, now struggling in his own form, is bound secured by the gods, who, carrying him off to the upper world, demand that he shall order the Nibelungs to bring the treasure from their subterranean regions.

At last (and here we are in fourth scene) he is compelled to renounce the ring, by means of which he had hoped to rule the world. Before parting with it he pronounces his ban on the ring, vowing that it shall bring disaster and death upon every one who wears it until it returns to its original possessors. "As through curse to me it came, accursed be this ring!" The mist in the foreground now gradually disperses; and the giants, with Freia, appear to claim their reward. Fasolt asks for gold sufficient to cover their prisoner (Freia) from head to foot. Loge and Froh thereupon begin to pile up the treasure so as to hide the precious goddess from sight. The treasure is exhausted, yet a chink remains through which the fair Freai remains visible to her oppressors. Fasolt, discerning the gleam of Freia’s eye, insists on a full equivalent for renouncing the goddess. Fafner demands the ring, which Wotan refuses. The giants wrathfully threaten to break the bargain and are on the point of bearing off Freia a second time when the stage grows dark, and from a rocky cleft rises up Erda, pantheistic symbol of Earth, the mother of the Fates. In solemn words she warns Wotan to give up the ring. Wotan obeys, throwing the bauble on the golden heap, which the giants at once proceed to collect in a huge sack.

But no sooner have they touched the ring than its curse begins to operate. Fafner and Fasolt both claim exclusive possessions of the ring. They quarrel over it, and in the broil Fafner kills Fasolt. The gods stand by in dumb amazement, realizing now the import of Erda’s warning. Fafner meanwhile makes off with the treasure, thus fulfilling the curse. Fricka signs to Wotan to enter Walhalla, and Wotan consents. Next, Donner (the god of thunder) and Froh proceed to clear the air of mists and clouds, Donner mounting a rocky eminence and swinging his hammer. Wotan hails Walhalla with delight, and as he leads to gods and goddesses towards the bridge, the city of the Rhine-daughters is heard from below. Loge informs the maidens that the gold will not be restored to them; and, as the curtain falls, the gods enter Walhalla by a rainbow which Froh has thrown across the valley of the Rhine, while below is still heard the eerie dirge of the Rhine-daughters, lamenting their lost treasure.

Such is the story of "The Rhinegold," remarkable among the later works of its composer for brevity and concentration. It lacks in human interest, but, on the other hand, as Mr. Streatfeild has remarked, its supernatural machinery is complete. The denizens of the world are grouped in four divisions -- gods in heaven, giants on earth, dwarfs beneath, water-sprites in the Rhine. The work has a freshness and an open-air feeling eminently suitable to the prologue of a trilogy which deals so much with the vast forces of Nature. Musically, it hardly ranks with its successors; but some of its tonal pictures -- the lovely opening scene and the grand closing march to Walhalla, for instance -- it would be difficult to match throughout the glowing gallery of "The Ring."

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |