Music with Ease > Operas of Richard Wagner > Götterdämmerung (Wagner) - Synopsis

Götterdämmerung - Synopsis

(English title: Twilight of the Gods)

An Opera by Richard Wagner

CHARACTERS

SIEGFRIED…………………………………. Tenor

GUNTHER…………………………………. Baritone

ALBERICH………………………………… Baritone

HAGEN…………………………………….. Bass

BRUNNHILDE…………………………….. Soprano

GUTRUNE…………………………………. Soprano

WALTRAUTE……………………………… Mezzo-Soprano

FIRST, SECOND AND THIRD NORN…… Contralto,Mezzo-Soprano, & Soprano

WOGLINDE, WELLGUNDE, & FLOSSHILDE...Sopranos & Mezzo-Soprano

Vassals and Women.

Time: Legendary.

Place: On the Brünnhilde-Rock; Gunther’s castle on the Rhine; wooded district by the Rhine.

THE PROLOGUE

The first scene of the prologue is a weird conference of the three grey sisters of fate -- the Norns who wind the skein of life. They have met on the Valkyrs’ rock and their words forebode the end of the gods. At last the skein they have been winding breaks -- the final catastrophe is impending.

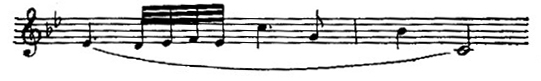

An orchestral interlude depicts the transition from the unearthly gloom of the Norn scene to break of day, the climax being reached in a majestic burst of music as Siegfried and Brünnhilde, he in full armour, she leading her steed by the bridle, issue forth from the rocky cavern in the background. This climax owes its eloquence to three motives -- that of the Ride of the Valkyrs and two new motives the one as lovely as the other is heroic, the Brünnhilde Motive,

and the Motive of Siegfried the Hero:

The Brünnhilde Motive expresses the strain of pure, tender womanhood in the nature of the former Valkyr, and proclaims her womanly ecstasy over wholly requited love. The motive of Siegfried the Hero is clearly developed from the motive of Siegfried the Fearless. Fearless youth has developed into heroic man. In this scene Brünnhilde and Siegfried plight their troth, and Siegfried having given to Bunnhilde the fatal ring and having received from her the steed Grane, which once bore her in her wild course through the storm-clouds, bids her farewell and sets forth in quest of further adventure. In this scene, one of Wagner’s most beautiful creations, occur the two new motives already quoted, and a third -- the Motive of Bunnhilde’s Love.

A strong, deep woman’s nature has given herself up to love. Her passion is as strong and deep as her nature. It is not a surface-heat passion. It is love rising from the depths of a heroic woman’s soul. The grandeur of her ideal of Siegfried, her thoughts of him as a hero winning fame, her pride in his prowess, her love for one whom she deems her bravest among men, culminate in the Motive of Brünnhilde’s Love.

Siegfried disappears with the steed behind the rocks and Brünnhilde stands upon the cliff looking down the valley after him; his horn is heard from below and Brünnhilde with rapturous gesture waves him farewell. The orchestra accompanies the action with the Brunhilde Motive, the Motive of Siegfried the Fearless, and finally with the theme of the love-duet with which "Siegfried" closed.

The curtain then falls, and between the prologue and the first act an orchestral interlude describes Siegfried’s voyage down the Rhine to the castle of the Gibichungs where dwell Gunther, his sister Gutrune, and their half-brother Hagen, the son of Alberich. Through Hagen the curse hurled by Alberich in "The Rhinegold" at all into whose possession the ring shall come, is to be worked out to the end of its fell purpose -- Siegfried betrayed and destroyed and the rule of the gods brought to an end by Brünnhilde’s expiation.

In the interlude between the prologue and the first act we first hear the brilliant Motive of Siegfried the Fearless and then the gracefully flowing Motives of the Rhine, and of the Rhinedaughters’ Shout of Triumph with the Motives of the Rhinegold and Ring. Hagen’s malevolent plotting, of which we are soon to learn in the first act is foreshadowed by the sombre harmonies which suddenly pervade the music.

Act I. On the river lies the hall of the Gibichungs, where house Gunther, his sister Gutrune, and Hagen, their half-brother. Gutrune is a maiden of fair mien, Gunther a man of average strength and courage, Hagen a sinister plotter, large of stature and sombre of visage. Long he has planned to possess himself of the ring fashioned of Rhinegold. He is aware that it was guarded by the dragon, has been taken from the hoard by Siegfried, and by him given to Brünnhilde. And now observe the subtle craft with which he prepares to compass his plans.

A descendant, through his father, Alberich, the Nibelung of a race which practiced the black art, he plots to make Siegfried forget Brünnhilde through a love-potion to be administered to him by Gutrune. Then, when under the fiery influence of the potion and all forgetful of Brünnhilde, Siegfried demands Gutrune to wife, the price demanded will be that he win Brünnhilde as bride for Gunther. Before Siegfried comes in sight, before Gunther and Gutrune so much as even know that he is nearing the hall of the Gibichungs, Hagen begins to lay the foundation for this seemingly impossible plot. For it is at this opportune moment Gunther chances to address him:

"Hark, Hagen, and let your answer be true. Do I head the race of the Gibichungs with honour?"

"Aye," replies Hagen, "and yet, Gunther, you remain unwived while Gutrune still lacks a husband." Then he tells Gunther of Brünnhilde -- "a circle of flame surrounds the rock on which she dwells, but he who can brave that fire may win her for wife. If Siegfried does this in your stead, and brings her to you as bride, will she not be yours?" Hagen craftily conceals from his half-brother and from Gutrune the fact that Siegfried already has won Brünnhilde for himself; but having aroused in Gunther the desire to possess her, he forthwith unfolds his plan and reminds Gutrune of the magic love-potion which it is in her power to administer to Siegfried.

At the very beginning of this act the Hagen Motive is heard. Particularly noticeable in it are the first two sharp, decisive chords. They recur with dramatic force in the third act when Hagen slays Siegfried. The Hagen Motive is as follows:

This is followed by the Gibichung Motive, the two motives being frequently heard in the opening scene.

Added to these is the Motive of the Love Potion which is to cause Siegfried to forget Brünnhilde, and conceive a violent passion for Gutrune.

What hesitation may have been in Gutrune’s mind, because of the trick which is involved in the plot, vanishes when soon afterwards Siegfried’s horn-call announces his approach from the river, and, as he brings his boat up to the bank, she sees this hero among men in all his youthful strength and beauty. She hastily withdraws, to carry out her part in the plot that is to bind him to her.

The three men remain to parley. Hagen skillfully questions Siegfried regarding his combat with the dragon. Has he taken nothing from the hoard?

"Only a ring, which I have left in a woman’s keep," answers Siegfried; "and this." He points to a steel network that hangs from his girdle.

"Ha," exclaims Hagen, "the Tarnhelmet! I recognize it as the artful work of the Nibelungs. Place it on your head and it enables you to assume any guise." He then flings open a door and on the platform of a short flight of steps that leads up to it, stands Gutrune, in her hand a drinking-horn which she extends toward Siegfried.

"Welcome, guest, to the house of the Gibichungs. A daughter of the race extends to you this greeting." And so, while Hagen looks grimly on, the fair Gutrune offers Siegfried the draught that is to transform his whole nature. Courteously, but without regarding her with more than friendly interest, Siegfried takes the horn from her hands and drains it. As if a new element coursed through his veins, there is a sudden change in his manner. Handing the horn back to her he regards her with fiery glances, she blushingly lowering her eyes and withdrawing to the inner apartment. New in this scene is the Gutrune Motive:

"Gunther, your sister’s name? Have you a wife?" Siegfried asks excitedly.

"I have set my heart on a woman," replies Gunther, "but may not win her. A far-off rock, fire-encircled, is her home."

"A far-off rock, fire encircled," repeats Siegfried, as if striving to remember something long forgotten; and when Gunther utters Brünnhilde’s name, Siegfried shows by his mien and gesture that it no longer signifies aught to him. The love-potion has caused him to forget her.

"I will press through the circle of flame," he exclaims. "I will seize her and bring her to you -- if you will give me Gutrune for wife."

And so the unhallowed bargain is struck and sealed with the oath of blood-brotherhood, and Siegfried departs with Gunther to capture Brünnhilde as bride for the Gibichung. The compact of blood-brotherhood is a most sacred one. Siegfried and Gunther each with his sword draws blood from his arm, which he allows to mingle with wine in a drinking-horn held by Hagen; each lays two fingers upon the horn, and then, having pledged blood-brotherhood, drinks the blood and wine. This ceremony is significantly introduced by the Motive of the Curse followed by the Motive of Compact. Phrases of Siegfried’s and Gunther’s pledge are set to a new motive whose forceful simplicity effectively expresses the idea of truth. It is the Motive of the Vow.

Abruptly following Siegfried’s pledge:

Thus I drink thee troth,

are those two chords of the Hagen Motive which are heard again in the third act when the Nibelung has slain Siegfried. It should perhaps be repeated here that Gunther is not aware of the union which existed between Brünnhilde and Siegfried, Hagen having concealed this from his half-brother, who believes that he will receive the Valkyr in all her goddess-like virginity.

When Siegfried and Gunther have departed and Gutrune, having sighed her farewell after her lover, has retired, Hagen broods with wicked glee over the successful inauguration of his plot. During a brief orchestral interlude a drop-curtain conceals the scene which when the curtain again rises, has changed to the Valkyr’s rock, where sits Brünnhilde, lost in contemplation of the Ring, while the Motive of Siegfried the Protector is heard on the orchestra like a blissful memory of the love scene in "Siegfried."

Her rapturous reminiscences are interrupted by the sounds of an approaching storm and from the dark cloud there issues one of the Valkyrs, Waltraute, who comes to ask of Brünnhilde that she cast back the ring Siegfried has given her -- the ring cursed by Alberich -- into the Rhine, and thus lift the curse from the race of gods. But Brünnhilde refuses:

More than Walhalla’s welfare,

More than the good of the gods,

The ring I guard.

It is dusk. The magic fire rising from the valley throws a glow over the landscape. The notes of Siegfried’s horn are heard. Brünnhilde joyously prepares to meet him. Suddenly she sees a stranger leap through the flames. It is Siegfried, but through the Tarnhelmet (the motive of which, followed by the Gunther Motive dominates the first part of the scene) he has assumed the guise of the Gibichung. In vain Brünnhilde seeks to defend herself with the might which the ring imparts. She is powerless against the intruder. As he tears the ring from her finger, the Motive of the Curse resounds with tragic import, followed by trist echoes of the Motive of Siegfried the Protector and of the Brünnhilde Motive, the last being succeeded by the Tarnhelmet Motive expressive of the evil magic which has wrought this change in Siegfried. Brünnhilde in abject recognition of her impotence, enters the cavern. Before Siegfried follows her he draws his sword Nothung (Needful) and exclaims:

Now, Nothung, witness thou, that chaste my wooing is;

To keep my faith with my brother, separate me from his bride.

Phrases of the pledge of Brotherhood followed by the Brünnhilde, Gutrune, and Sword motives accompany his words. The thuds of the typical Nibelung rhythm resound, and lead to the last crashing chord of this eventful act.

Act II. The ominous Motive of the Nibelung’s Malevolence introduces the second act. The curtain rises upon the exterior of the hall of the Gibichungs. To the right is the open entrance to the hall, to the left the bank of the Rhine, from which rises a rocky ascent toward the background. It is night. Hagen, spear in hand and shield at side, leans in sleep against a pillar of the hall. Through the weird moonlight Alberich appears. He urges Hagen to murder Siegfried and to seize the ring from his finger. After hearing Hagen’s oath that he will be aithful to the hate he has inherited, Alberich disappears. The weirdness of the surroundings, the monotony of Hagen’s answers, uttered seemingly in sleep, as if, even when the Nibelung slumbered, his mind remained active, imbue this scene with mystery.

A charming orchestral interlude depicts the break of day. Its serene beauty is, however, broken in upon by the Motive of Hagen’s Wicked Glee, which I quote, as it frequently occurs in the course of succeeding events.

All night Hagen has watched by the bank of the river for the return of the men from the quest. It is daylight when Siegfried returns, tells him of his success, and bids him prepare to receive Gunther and Brünnhilde. On his finger he wears the ring -- the ring made of Rhinegold, and cursed by Alberich -- the same with which he pledged his troth to Brünnhilde, but which in the struggle of the night, and disguised by the Tarnhelmet as Gunther, he has torn from her fingers -- the very ring the possession of which Hagen craves, and for which he is plotting. Gutrune has joined them. Siegfried leads her into the hall.

Hagen, placing an ox-horn to his lips, blows a loud call toward the four points of the compass, summoning the Gibichung vassals to the festivities attending the double wedding -- Siegfried and Gutrune, Gunther and Brünnhilde; and when the Gibichung brings his boat up to the bank, the shore is crowded with men who greet him boisterously, while Brünnhilde stands there pale and with downcast eyes. But as Siegfried leads Gutrune forward to meet Gunther and his bride, and Gunther calls Siegfried by name, Brünnhilde starts, raises her eyes, stares at Siegfried in amazement, drops Gunther’s hand, advances, as if by sudfden impulse, a step toward the man who awakened her from her magic slumber on the rock, then recoils in horror, her eyes fixed upon him, while all look on in wonder. The Motive of Siegfried the Hero, the Sword Motive, and the Chords of the Hagen Motive emphasize with a tumultuous crash the dramatic significance of the situation. There is a sudden hush -- Brünnhilde astounded and dumb, Siegfried unconscious of guilt quietly self-possessed, Gunther, Gutrune, and the vassals silent with amazement -- it is during this moment of tension that we hear the motive which expresses the thought uppermost in Brünnhilde, the thought which would find expression in a burst of frenzy were not her wrath held in check by her inability to quite grasp the meaning of the situation or to fathom the depth of the treachery of which she has been the victim. This is the Motive of Vengeance:

"What troubles Brünnhilde?" composedly asks Siegfried, from whom all memory of his first meeting with the rock maiden and his love for here have been effaced by the potion. Then, observing that she sways and is about to fall, he supports her with his arm.

"Siegfried knows me not!" she whispers faintly, as she looks up into his face.

"There stands your husband," is Siegfried’s reply, as he points to Gunther. The gesture discloses to Brünnhilde’s sight the ring upon his finger, the ring he gave her, and which to her horror Gunther, as she supposed, had wrested from her. In the flash of its precious metal she sees the whole significance of the wretched situation in which she finds herself, and discovers the intrigue, the trick, of which she has been the victim. She knows nothing, however, of the treachery Hagen is plotting, or of the love-potion that has aroused in Siegfried an uncontrollable passion to possess Gutrune, has caused him to forget her, and led him to win her to Gunther. There at Gutrune’s side, and about to wed her, stands the man she loves. To Brünnhilde, infuriated with jealousy, her pride wounded to the quick, Siegfried appears simply to have betrayed her to Gunther through infatuation for another woman.

"The ring," she cries out, "was taken from me by that man," pointing to Gunther. "How came it on your finger? Or, if it is not the ring" -- again she addresses Gunther -- "where is the one you tore from my hand?"

Gunther, knowing nothing about the ring, plainly is perplexed. "Ha," cries out Brünnhilde in uncontrollable rage, "then it was Siegfried disguised as you and not you yourself who won it from me1 Know then, Gunther, that you, too, have been betrayed by him. For this man who would wed your sister, and as part of the price bring me to you as bride, was wedded to me!"

In all but Hagen and Siegfried, Brünnhilde’s words arouse consternation. Hagen, noting their effect on Gunther, from whom he craftily has concealed Siegfried’s true relation to Brünnhilde, sees in the episode an added opportunity to mould the Gibichung to his plan to do away with Siegfried. The latter, through the effect of the portion, is rendred wholly unconscious of the truth of what Brünnhilde has said. He even has forgotten that he ever has parted with the ring, and, when the man, jealous of Gunther’s honour, crowd about him, and Gunther and Gutrune in intense excitement wait on his reply, he calmly proclaims that he found it among the dragon’s treasure and never has parted with it. To the truth of this assertion, to a denial of all Brünnhilde has accused him of, he announces himself ready to swear at the point of any spear which is offered for the oath, the strongest manner in which the asseveration can be made and, in the belief of the time, rendering his death certain at the point of that very spear should be swear falsely.

How eloquent the music of these exciting scenes! -- Crashing chords of the Ring Motive followed by that of the Curse, as Brünnhilde recognizes the ring on Siegfried’s finger, the Motive of Vengeance, the Walhalla Motive, as she invokes the gods to witness her humiliation, the touchingly pathetic Motive of Brünnhilde’s Pleading, as she vainly strives to awaken fond memories in Siegfried; then again the Motive of Vengeance, as the oath is about to be taken, the Murder Motive and the Hagen Motive at the taking of the oath, for the spear is Hagen’s; and in Brünnhilde’s asseveration, the Valkyr music coursing through the orchestra.

It is Hagen who offers his weapon for the oath. "Guardian of honour, hallowed weapon," swears Siegfried, "where steel can pierce me, there piece me; where death can be dealt me, there deal it me, if ever I was wed to Brünnhilde, if ever I have wronged Gutrune’s brother."

At his sword, Brünnhilde, livid with rage, strides into the circle of men, and thrusting Siegfried fingers away from the spearhead, lays her own upon it.

"Guardian of honour, hallowed weapon," she cries, "I dedicate your steel to his destruction. I bless your point that it may blight him. For broken are all his oaths, and perjured now he proves himself."

Siegfried shrugs his shoulders. To him Brünnhilde’s imprecations are but the ravings of an overwrought brain. "Gunther, look to your lady. Give the tameless mountain maid time to rest and recover," he calls out to Gutrune’s brother. "And now, men, follow us to table, and make merry at our wedding feast!" Then with a laugh and in highest spirits, he throws his arm about Gutrune and draws her after him into the hall, the vassals and women following them.

But Brünnhilde, Hagen, and Gunther remain behind; Bunnhilde half stunned at sight of the man with whom she has exchanged troth, gaily leading another to marriage, as though his vow had been mere chaff; Gunther, suspicious that his honour wittingly has been betrayed by Siegfried, and that Brünnhilde’s words are true. Hagen, in whose hands Gunther is like clay, waiting the opportunity to prompt both Brünnhilde and his half-brother to vengeance.

"Coward," cries Brünnhilde to Gunther, "to hide behind another in order to undo me! Has the race of the Gibichungs fallen so low in prowess?"

"Deceiver, and yet deceived! Betrayed, and yet myself betrayed," wails Gunther. "Hagen, wise one, have you no counsel?’

"No counsel," grimly answers Hagen, "save Siegfried's death."

"His death.’"

"Aye, all these things demand his death."

"But, Gutrune, to whom I gave him, how would we stand with her if we so avenged ourselves?" For even in his injured pride Gunther feels that he has had a share in what Siegfried has done.

But Hagen is prepared with a plan that will free Gunther and himself of all accusation. "To-morrow," he suggests, "we will go on a great hunt. As Siegfried boldly rushes ahead we will fell him from the rear, and give out that he was killed by a wild boar."

"So be it," exclaims Brünnhilde; "let his death atone for the shame he has wrought me. He has violated his oath; he shall die!"

At that moment as they turn toward the hall, he whose death they have decreed, a wreath of oak on his brow and leading Gutrune, whose hair is bedecked with flowers, steps out on the threshold as though wondering at their delay and urges them to enter. Gunther, taking Brünnhilde by the hand, follows him in. Hagen alone remains behind, and with a look of grim triumph watches them as they disappear within. And so, although the valley of the Rhine reechoes with glad sounds, it is the Murder Motive that brings the act to a close.

Act III. How picturesque the mise-en-scene of this act -- a clearing in the forest primeval near a spot where the bank of the Rhine slopes toward the river. On the shore, above the stream, stands Siegfried. Baffled in the pursuit of game, he is looking for Gunther, Hagen, and his other comrades of the hunt, in order to join them.

One of the loveliest scenes of the trilogy now ensues. The Rhinedaughters swim up to the bank and, circling gracefully in the current of the river, endeavour to coax from him the ring of Rhinegold. It is an episode full of whimsical badinage and, if anything, more charming even than the opening of "Rhinegold."

Siegfried refuses to give up the ring. The Rhinedaughters swim off leaving him to his fate.

Here is the principal theme of their song in this scene:

Distant hunting-horns are heard. Gunther, Hagen, and their attendants gradually assemble and encamp themselves. Hagen fills a drinking-horn and hands it to Siegfried whom he persuades to relate the story of his life. This Siegfried does in a wonderfully picturesque, musical, and dramatic story in which motives, often heard before, charm us anew.

In the course of his narrative he refreshes himself by a draught from the drinking-horn into which meanwhile Hagen has pressed the juice of an herb. Through this the effect of the love-potion is so far counteracted that tender memories of Brünnhilde well up within him and he tells with artless enthusiasm how he penetrated the circle of flame about the Valkyr, found Brünnhilde slumbering there, awoke her with his kiss, and won her. Gunther springs up aghast at this revelation. Now he knows that Brünnhilde’s accusation is true.

Two ravens fly overhead. As Siegfried turns to look after them the Motive of the Curse resounds and Hagen plunges his spear into the young hero’s back. Gunther and the vassals throw themselves upon Hagen. The Siegfried Motive, cut short with a crashing chord, the two murderous chords of the Hagen Motive forming the bass -- and Siegfried, who with a last effort has heaved his shield aloft to hurl it at Hagen, lets it fall, and, collapsing, drops upon it. So overpowered are the witnesses -- even Gunther -- by the suddenness and enormity of the crime that, after a few disjointed exclamations, they gather, bowed with grief, around Siegfried. Hagen, with stony indifference turns away and disappears over the height.

With the fall of the last scion of the Wälsung race we hear a new motive, simple yet indescribably fraught with sorrow, the Death Motive.

Siegfried, supported by two men rises, to a sitting posture, and with a strange rapture gleaming in his glance, intones his death-song. It is an ecstatic greeting to Brünnhilde. "Brünnhilde!" he exclaims, "thy wakener comes to wake thee with his kiss." The ethereal harmonies of the Motive of Brünnhilde’s Awakening, the Motive of Fate, the Siegfried Motive swelling into the Motive of Love’s Greeting and dying away through the Motive of Love’s Passion to Siegfried’s last whispered accents -- "Brünnhilde beckons to me" -- in the Motive of Fate -- and Siegfried sinks back in death.

Full of pathos though this episode be, it but brings us to the threshold of a scene of such overwhelming power that it may without exaggeration be singled out as the supreme musico-dramatic climax of all that Wagner wrought, indeed of all music. Siegfried’s last ecstatic greeting to his Valkyr bride has made us realize the blackness of the treachery which tore the young hero and Brünnhilde asunder and led to his death; and now as we are bowed down with a grief too deep for utterance -- like the grief with which a nation gathers at the grave of its noblest hero -- Wagner voices for us, in music of overwhelmingly tragic power, feelings which are beyond expression in human speech. This is not a "funeral march," as it is often absurdly called -- it is the awful mystery of death itself expressed in music.

Motionless with grief men gather around Siegfried’s corpse. Night falls. The moon casts a pale, sad light over the scene. At the silent bidding of Gunther the vassals raise the body and bear it in solemn procession over the rocky height. Meanwhile with majestic solemnity the orchestra voices the funeral oration of the "world’s greatest hero." One by one, but tragically interrupted by the Motive of Death, we hear the motives which tell the story of the Wälsung’s futile struggle with destiny- the Wälsung Motive, the Motive of the Wälsung’s Heroism, the Motive of Sympathy, the Love Motive, the Sword Motive, the Siegfried Motive, and the Motive of Siegfried the Hero, around which the death Motive swirls and crashes like a black, death-dealing, all-wrecking flood, forming an overwhelming powerful climax that dies away into the Brünnhilde Motive with which, as with a heart-broken sign, the heroic dirge is brought to the a close.

Meanwhile the scene has changed to the Hall of the Gibichungs as in the first act. Gutrune is listening through the night for some sound which may announce the return of the hunt.

Men and women bearing torches precede in great agitation the funeral train. Hagen grimly announces to Gutrune that Siegfried is dead. Wild with grief she overwhelms Gunther with violent accusations. He points to Hagen whose sole reply is to demand the ring as spoil. Gunther refuses. Hagen draws his sword and after a brief combat slays Gunther. He is about to snatch the ring from Siegfried’s finger, when the corpse’s hand suddenly raises itself threateningly, and all -- even Hagen -- fall back in consternation.

Brünnhilde advances solemnly from the back. While watching on the bank of the Rhine she has learned from the Rhinedaughters the treachery of which she and Siegfried have been the victims. Her mien is ennobled by a look of tragic exaltation. To her the grief of Gutrune is but the whining of a child. When the latter realizes that it was Brünnhilde whom she caused Siegfried to forget through the love-potion, she falls fainting over Gunther’s body. Hagen leaning on his spear is lost in gloomy brooding.

Brünnhilde turns solemnly to the men and women and bids them erect a funeral pyre. The orchestral harmonies shimmer with the Magic Fire Motive through which courses the Motive of the Ride of the Valkyrs. Then, her countenance transfigured by love, she gazes upon her dead hero and apostrophizes his memory in the Motive of Love’s Greeting. From him she looks upward and in the Walhalla Motive and the Motive of Brünnhilde’s Pleading passionately inveighs against the injustice of the gods. The Curse Motive is followed by a wonderfully beautiful combination of the Walhalla Motive and the Motive of the God’s Stress at Brünnhilde’s words:

Rest thee! Rest thee! O, God!

For with the fading away of Walhalla, and the inauguration of the reign of human love in place of that of lust and greed -- a change to be wrought by the approaching expiation of Brünnhilde for the crimes which began with the wresting of the Rhinegold from the Rhinedaughters -- Wotan’s stress will be at an end. Brünnhilde having told in the graceful, rippling Rhine music how she learned of Hagen’s treachery through the Rhinedaughters, places upon her finger the ring. Then turning toward the pyre upon which Siegfried’s body rests, she snatches a huge firebrand from one of the men, and flings it upon the pyre, which kindles brightly. As the moment of her immolation approaches the Motive of Expiation begins to dominate the scene.

Brünnhilde mounts her Valkyr charger, Grane, who oft bore her through the clouds, while lightning flashed and thunder reverberated. With one leap the steed bears her into the blazing pyre.

The Rhine overflows. Borne on the flood, the Rhinedaughters swim to the pyre and draw, from Brünnhilde’s finger, the ring. Hagen, seeing the object of all his plotting in their possession, plunges after them. Two of them encircle him with their arms and draw him down with them into the flood. The third holds up the ring it triumph.

In the heavens is perceived a deep glow. It is Gotterdammerung -- the dusk of the gods. An epoch has come to a close. Valhalla is in flames. Once more its stately motive resounds, only to crumble, like a ruin, before the onsweeping power of the motive of expiation. The Siegfried Motive with a crash in the orchestra; once more then the Motive of Expiation. The sordid empire of the gods has passed away. A new era, that of human love, has dawned through the expiation of Brünnhilde. As in "The Flying Dutchman" and "Tannhäuser," it is through woman that comes redemption.

Music With Ease | About Us | Contact Us | Privacy | Sitemap | Copyright | Terms of Use © 2005-23 musicwithease.com. All Rights Reserved. |